Everything posted by Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

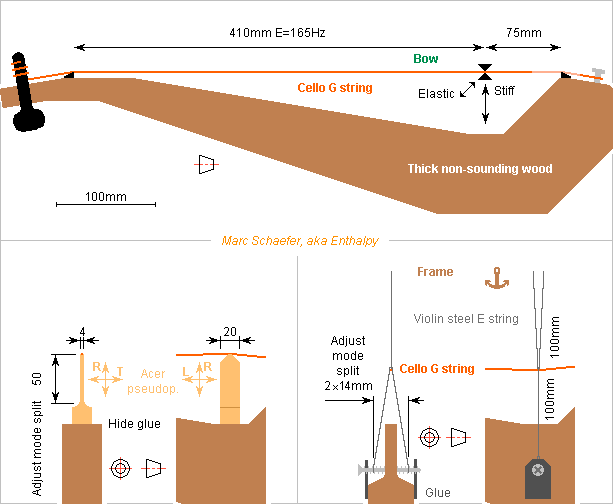

To check the explanation I proposed for the wolf tone, the experimental setup could look like this. At left a bridge is flexible laterally, at right it's a steel string. Here at least the vertical modes of the string are harmonic thanks to the boundary conditions and the uniform lineic mass. Horizontal compliance lowers the string's horizontal mode by adjustable 4Hz from E=165Hz. This results from the equivalent of 20mm extra length, that is horizontal 6.0kN/m side stiffness of the imperfect node. The string's non-speaking length keeps its damping yarn and it can be 75mm to have no common low harmonic with the speaking length (I checked only the vertical modes). The stiffness of these 75mm with 120N string tension leaves horizontal 4.4kN/m obtained from the tweaked bridges. 1mm is the maximum lateral deviation of the non-speaking length of the string at the tweaked bridges. ========== The flexible wooden part (left on the sketch) uses stiff glue. Mind the wood's orientation. The height of the thin section adjusts the frequency drop of the string's horizontal mode. At right on the sketch, a violin E string of 0.25mm unspun steel serves as a pseudo-bridge. Some 12.6N tension would resonate the 100mm at 902Hz to avoid common harmonics with the cello string, but more tension may be better, and additional reasonable damping looks useful. The violin string is bent sharp pemanently. The mere tension of the four 100mm sections brings 0.5kN/m horizontal stiffness, and the adjustable 2*14mm width of the Lambda shape 4.0kN/m more. A reasonably sturdy wooden frame, not displayed on the sketch, holds the upper V made of violin string. ========== If a wold tone appears in this setup with no soundbox resonance, it will favour my explanation. Many cello strings are ferromagnetic, useful to excite each mode separately. A repetition rate of the wolf tone near the frequency difference between the modes would be a further argument. Both variants of the setup let adjust the frequency difference. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

The wolf tone is a sound instability that can appear on celli and double basses, rarely on violins de.wikipedia (audio) en.wikipedia - schleske.de/de - schleske.de/en theories exist, essentially a strong body resonance that couples too much with the string. These theories match some observations but fit others imperfectly. A string can and does vibrate in any perpendicular direction, plus all the combinations, which includes elliptic modes. If the bridge is stiff, all modes have the same frequency. But if the soundbox resonates strongly, the bridge is more mobile, which lowers the string's frequency, and more so in one direction decided by the soundbox' behaviour. The string modes split in two that have different frequencies and can beat. The split may be more common at celli and double basses because their bridge is tall and narrow, so body resonances matter more to the string in the transverse direction. I suggest to inject this mode split in the current theories. Some experimental checks: If the wolf tone persists when a single string remains on the instrument, try unusual bowing directions, observe if they have an influence. Will that be convincing? On a hauling cello, use a capodastro, check by an actuator if the string has split modes and if their frequency difference matches the beat when bowing. Build a pseudo-instrument with a string but no soundbox, where the bridge is stiff in one direction but flexible in the other, for instance steel wire in V shape, or flat wood aligned with the string, preferably at 45° with the bow. Check if the wolf tone appears with the mode split but without any body resonance. Measure both modes, check if the instability's frequency is the difference of them. Pluck the string, compare with the bow. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

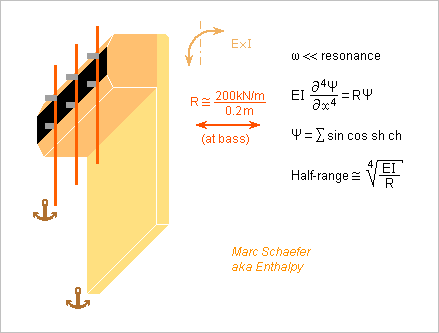

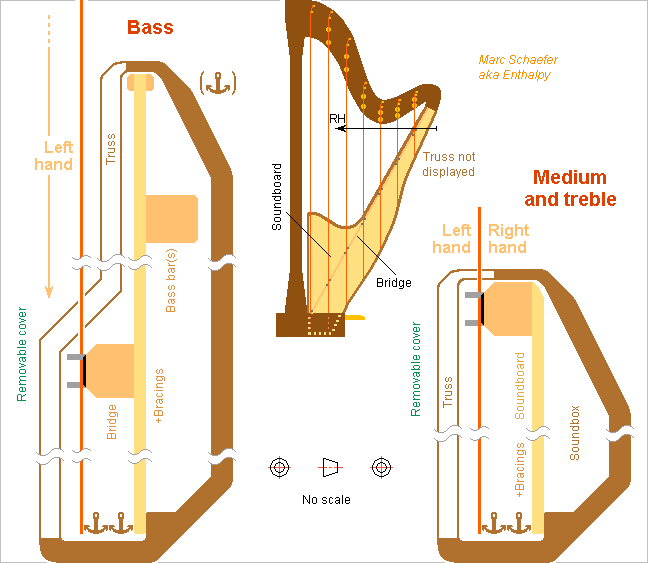

Estimated bridge stiffness required by my two harp designs with vertical soundboard. From the previous message, the bass strings should feel about 200kN/m, and if the bridge is to spread the side movements over +-0.1m, R~1MN/m2. The bridge must be stiff enough for that: EI~100N*m2. Beech (E=12GPa) needs W=e=18mm. If it sounds decently, 1D graphite (170GPa) on wood needs e=1+12+1mm W=7mm, a bit lighter. Medium and trebles need different dimensions. ========== At its column end, the bridge could be anchored with elasticity so the lowest strings feel a good stiffness and move the soundboard at the higher strings too. The unstressed soundboard can hold at its top ridge under the bass strings, and be free at the bottom. ========== Imagine that the narrow tall soundbox contains 0.03m3=210nF with the unstressed soundboard. The lowest H2 has 62Hz and we don't hear fundamentals lower. For arbitrary 1Parms in the box, the power radiated by the small source is 0.15µW while conduction to 0.6m2 box wastes 0.03µW, so it's big enough for that. Air elasticity pushing on equivalent 0.2m2 at the bass bridge portion adds 200kN/m stiffness, the full stiffness goal, so the box could be slightly bigger or the soundboard smaller. If the equipped soundboard brings 150g equivalent inertia and the bass strings too, air elasticity resonates them near 130Hz. Fluffy material in the box can dampen this resonance. My designs have leaks around the soundboard, say 1mm*1.6m wide and 15mm long. At 62Hz and for 1Parms in the box, inertia limits them to 0.14m/s and 0.2dm3/s compared with radiated 0.08dm3/s. The leak intensity improves with the frequency squared and the box volume, and it's nearly in phase quadrature anyway, resembling more a Helmholtz resonance around 100Hz, combining with the previous 130Hz to make 160Hz. The leaks waste power by viscosity. For 1Parms at 62Hz hence 0.14m/s it's 16µW. This reduces the strings' decay time. The box volume improves this loss, holding the soundboard where possible too. Frequency improves all this quickly. At 140Hz, radiation equals viscous losses. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

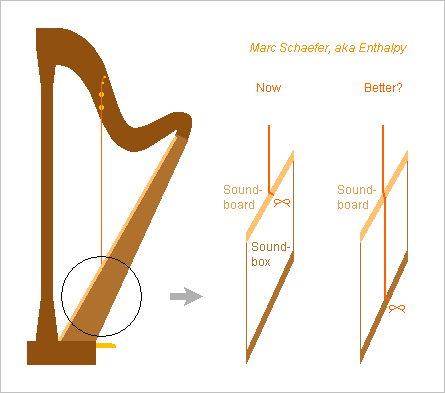

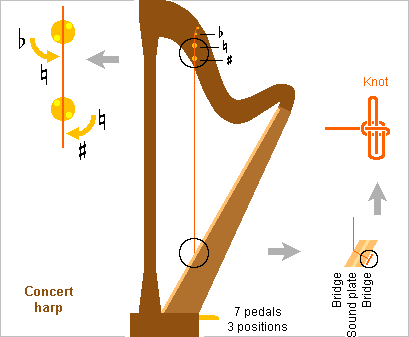

The soundboard of the usual concert harp, 8 to 10mm thin (my mistake) and 580mm wide, can't resist alone the traction of the low strings. The midrib (=bridge at present harps) does it there by holding at the pillar, but this makes the soundboard very stiff under the bass strings. The bass strings also resonate longer than needed, so a more compliant soundboard could be louder. Imagine that the soundboard flexes by 0 to 10mm under the 15 lowest strings that pull each mean 500N, that's roughly 1.5MN/m, neglecting all angles. Badly stiff. ========== Tone wood isn't flexible at identical bending resistance. Accordingly, the luthier Camac replaced at least the lower end with an aluminium bar. Material Pedantly Resistance Young Merit --------------------------------------------------------- Spruce Picea abies 70 12 49 Sycamore Acer pseudopl. 95 10 93 Beech Fagus Sylvatica 115 12 103 Yew Taxus baccata 105 9 120 Aluminum AA7075 480 72 146 Titanium Ti-Al6V4 830 114 210 Steel NiCoMoTi 18-9-5 2000 190 471 --------------------------------------------------------- R MPa E GPa R^1.5/E Steel would give more flexibility than aluminium. This lowers the resonances consequently. Thickness, and optionally profile, that vary with the position, can increase the soundboard's flexibility only at its wide but underused lower end. Or if keeping wood, a wider thinner end of yew (it made longbows and mandolines) should outperform spruce and sycamore. Additional parts can resist the force and give more flexibility than a straight bar, for instance a transverse bar. The soundboard must be thin to accept the deformation. The midrib's end can pull the soundboard low until the strings pull it up. The position of the midrib's end can be adjustable, at the factory or while the musician tightens the strings. I'd have stops at the midrib's end to protect the soundboard. ========== Kurijn Buys made seducing proposals for the harp's soundboard: Kurijn Buys' report (in French) decouple the soundboard from the column, build it from composite materials to resist the string's pull but be flexible, prestress it, among others. ========== My two versions of vertical soundboard are far more flexible. Over 180mm for the same 15 lowest strings, spruce 3mm thick and 200mm high contributes only 2kN/m bending stiffness, and 40MPa allow 27mm deflection. If fastened 200mm lower, the 7500N cumulated tension contribute 38kN/m, whether this tension is in the string extra length or in the soundboard. This oriented compliance lets a string swing slower, but only in the transverse mode. For a string tightened with 770N, this acts like 20mm extra length over 1.27m or 0.8% pitch mismatch, so the beat half-period is 0.8s, shorter than the exponential decay time. Around 5* stiffer, or 200kN/m, would be better in this register: fasten the strings 40mm below the bridge rather than 200mm, or add wood springs at the bridge. The unstressed design needs abundant bracings for adequate resonances. +-45° orientations may protect the soundboard better against in-plane traction by the musician. The tensile soundboard has a big wave speed parallel to the strings. 14MPa tension and 400kg/m3 give it 190m/s, so a half-wave in 200mm height give a lowest resonance at 470Hz without bracings. Resonances need only bracings perpendicular to the strings. But since this soundboard moves like a flat sheet, its base concentrates the bending stress and may demand some protection. My two designs seem to have design margins everywhere, including for thicker soundboards. With a radiating area similar to the present harp, but movements about 7.5* bigger, my designs should be 17dB louder, as much as 50 present harps. Could that be a first step towards the gaffophone? fr.wiki and google Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

Le Carrou used already a shallow chimney at one hole to indentify the Helmholtz resonance. How much would tall chimneys at harp holes bring? I take 100mm height at the holes Le Carrou measured. The narrower soundbox end isn't that deep, but it adds its own inductance. D131 (16.2H) // D120 (18.6H) // D111 (21.1H) // D89 (30.2H) = 5.1H which resonates the soundbox' volume at 154Hz, same as the soundboard at this harp model hence useless. This improves if doors shut some holes. 3mm elastomer are worth 2.2m air. The soundboard's compliance contributes too. With chimneys at the lowest holes (could be elsewhere), 2 holes resonate at 118Hz and 1 at 86Hz. Arbitrary 1Parms at 118Hz in the box would radiate 1.9µW, conduction would waste 0.1µW and viscosity >0.1µW, elastomer doors contribute, for Q<68. A rosace or narrow F-holes would increase the viscosity losses, as would leaving a single hole open with a shallower chimney. Fluffy material, as in loudspeakers, can dampen too strong resonances of the long air column in the almost-closed soundbox. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

A 237th check tells me eventally that the volume of the harp's soundbox isn't 0.2m3. It's nearer to 0.03m3, depending on the model, giving it 210nF capacity. This needs updates to my February 03, 2019, 11:33 PM message. Acoustic measurements of a harp exist there Le Carrou's thesis (mostly in French) The measured soundbox has 5 elliptical holes (table 3.1), of which I keep the 3 lowest. I assimilate their inductance to a disk of same area, which acts as a cylinder of length (0.3+0.3)*D: D131 (7.1H), D120 (7.8H), D111 (8.4H) total 2.6H to estimate the Helmholtz resonance at 216Hz. Le Carrou attributed it 172Hz rather, after subtle arguments since his fig 3.8 provides no obvious logic, probably because the soundbox isn't short. For instance, the strong resonance that appears at 190Hz with holes closed has lambda/2=0.9m, shorter than the soundbox. Can soundbox' resonances be brought usefully below 154Hz, the measured lowest soundboard resonance? I suggest resonating doors tuned to 123Hz, 99Hz, 79Hz, 63Hz. Of Acer pseudoplatanus, they could measure approximately 170mm*60mm*1.3mm, 190mm*70mm*1.4mm, 200mm*90mm*1.2mm, 210mm*100mm*1.1mm - or rather thicker with an adjusted mass in the middle. The last hole would resonate at 50Hz in Helmholz mode with 48H inductance resulting from an 185mm*85mm*0.8mm elastomer membrane. ...Maybe. The resonating doors need a non-absorbing airtight fastening. A harp that radiates low frequencies like a plucked contrabass may sound denatured. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

A sheet of elastomer can be a door for a harp's hole. Very few mm suffice to stop the air by inertia. It's easily silent and airtight. Strings could hold the door (or patch) at round hooks at the soundbox. The patch could even hold in the hole by a firm fit. I suppose the viscoelastic properties don't matter as the patch moves little. Polyurethanes resist wear best, while perfluoroelastomers are immune to chemical degradation. Of course, the finished patch must be nice. ========== Strings can also go through the soundboard of a loud chromatic harp as suggested here on January 20, 2019. The springs of January 27, 2019 02:30 PM apply, oriented stiffness as on January 27, 2019 04:32 PM too. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

Harps have presently big holes in their soundbox that let mount the strings from behind the soundboard. Though, the first role of a soundbox is to enclose the rear wave of the soundboard so it doesn't cancel the front wave. Many people are concerned with these holes, some proposed covers, mobile to access the strings, or even controlled by a pedal, but all this is abandoned. So how critical is the leak? At high frequencies, the soundbox' volume and capacitance builds little inside pressure, and the holes' inductance is big, so the rear wave doesn't exit, and the holes have no effect. Near the frequency where the holes' inductance resonates with the box' capacitance, the rear wave can be stronger than the front one and produce a stronger net sound, as for a violin's Helmholtz resonance. At lower frequencies, the inductance doesn't stop the rear wave which weakens the front wave - here the holes could be detrimental. A harp can emit a Cb=30.9Hz but we don't perceive fundamentals so low, only the harmonics above roughly 80Hz, and a soundboard also radiates the low frequencies badly. As grossly estimated from pictures - an acoustic measurement would be better: The soundbox is 1.6m long while lambda/4=1.1m at 80Hz, so it's not far from a lumped constants case: tweaking a bit suffices. The soundbox has 0.2m3 = 1.4µF, mostly near the bass strings, so I keep it fully. The 5 holes are 0.25m high each but I cumulate only 1m as a lumped constant. The walls are thin so the inductance results from cylindrical spreading between mean w=120mm to W=500mm: L = 1.225kg/m3*(2/pi)*Log(0.5m/0.12m)/1m = 1.1H (inside+outside). As much as 0.11m air thickness. The resonance is 128Hz very approximately. The loss is 4dB at 80Hz, not much. It worsens at lower frequencies that we perceive less. But around 128Hz, the resonance by the soundholes amplifies the sound (I didn't estimate the Q factor). So there's nothing damning in these convenient openings. Can we improve this? Doors strengthen the radiation at 80Hz but waste the resonance at 128Hz, possible explanation for the mixed opinions when they were tried. Shifting the resonance to 80Hz or slightly lower should be better - maybe. Make the soundbox bigger. Under the medium strings, it could be reasonably wider and deeper. Significant contribution, but it won't double the capacitance. Make smaller holes? No, harpists need big hands. Close every second hole with a door. Their seals shall absorb the vibration, but not too much. Put membranes on the holes. A 950kg/m3 material, 140µm thin, would double the inductance of 0.11m thick air. I doubt they can be silent (hear a sudrophone...) and durable too. Add chimneys to the holes in the box. If 0.11m long, they double the inductance and shouldn't hamper the hands' activities. They can broaden at depth. They would also strengthen the Helmholtz resonance, for good or bad, more so with rounded edges. Close some holes with resonating doors. Keep 3 from 5 effective holes open, the Helmholtz resonance drops to 100Hz. Let a door resonate mechanically at 80Hz, the other at 65Hz. Made flat of Acer pseudoplatanus, they must be around 2.3mm and 2.8mm thick, to be experimented, then adjusted individually at production. The doors can be bigger than 250mm*120mm and thicker. The holes are small at celtic harps. Chimeys or resonating doors would keep the resonant frequency and allow bigger holes. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

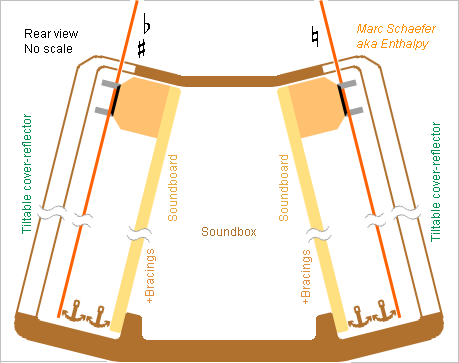

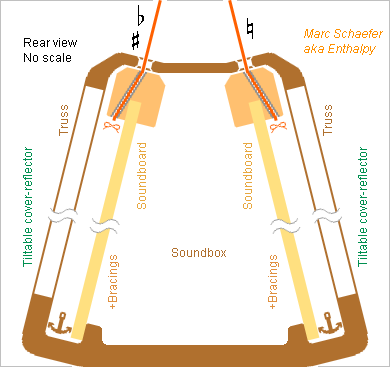

The chromatic harp is nearly extinct: it isn't taught for decades, the last instruments were built three-quarter century ago, most remaining ones are in a bad state. As one drawback, it is less loud than the concert harp, for which some simple reasons exist. The added strings add mass, stiffness, and they pull stronger at the soundboard. The strings pull excentred at the soundboard, which may or not need extra thickness, but for sure the soundboard is harder to move from an excentric point. My two arrangements solve that, with strings pulling in line with the sounboard or not at it. They need pairs of soundboards, one for each plane of strings (which I possibly swapped). Then a chromatic instrument would be as loud as the diatonic one which hopefully improves over the present design with flexed soundboard. The soundboards have some directivity at high notes and harmonics, so tilted reflectors that double as protective covers shall direct all notes in the same direction, essentially forward. The (cover-) reflector may apply to the diatonic versions too. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

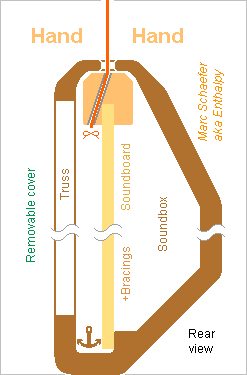

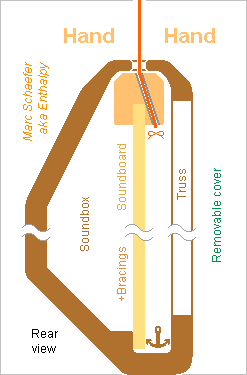

Here's a glipmse at a harp with unstressed soundboard inspired by the pianoforte, whose strings make only a zigzag at a bridge and continue to a frame. From descriptions of playing techniques, the musician must access the strings near the bridge too composingforharp.com but only the left hand reaches the lowest 10th, and the right hand stops even earlier near the soundboard, so I believe the soundboard can extend over the bridge at the right side of the two bass octaves; where it extends much, its rim can be attached. The soundboard can also extend deeper below the bridge in the medium, as depicted. Could the bridge be curved to run higher in the medium? This would put the strings' middle on a more regular curve, possibly ease playing, but change the musician's habits. The unstressed soundboard is much thinner than at present harps. It can be fastened at a position different from the strings. Abundant bracings, plus the bridge and possible bass bar(s), keep the resonances high enough. The bridge is a copy from a piano with the gliding layer and precise nails and wedges, reduced at the bass and much more at the treble. The bass strings too must extend below the bridge for compliance, hence between the left and right pedals. Opportunity to extend the soundboard too. A truss can improve the protection of the thin soundboard, protect the musician's legs against the nails, and close the traction-resisting section. Besides wood, fibre composites may perhaps constitute the soundbox' shell and the truss, or even cast metal, especially magnesium alloy, thin and with ribs - not only for this instrument. The soundbox being as narrow as the neck and pillar, folded or disassembled feet and pedals would make an instrument thin and easier to transport. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

The arrangement of symphonic orchestras fooled me, but harpists show their front to the public, slightly from the right side. So, the soundboard pulled at its edge by the strings, as depicted here on January 27, 2019 07:39 PM, shall better radiate to the left and have its soundbox at the right.

-

String Instruments

The next step is obviously to design a harp inspired by the piano arrangement: the strings run next to the soundboard parallel to it and make only a zigzag at a bridge to and end at a frame without pulling the soundboard. The arrangement resembles the previous message, so much of the description and the many advantages applies. Better, the soundboard can more easily extend higher than the end of the bass and medium strings to be bigger and louder. Details should come. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

Guitars have an ultra-thin soundboard, around 1mm, made possible because their strings pull parallel to it, not perpendicular. So here's a harp whose strings pull parallel to the soundboard. 20mm thickness resist (often) the perpendicular pull over some 250+250mm width, so for a parallel pull, a 2mm thin soundboard should suffice even at the bass strings: we're getting somewhere. Abundant bracings are necessary to keep decent resonant frequencies. The strings pull at the upper end of the soundboard, at least at the treble end, so that both hands reach the strings. The soundbox' shell doesn't touch the soundboard near the strings, but it passes close to the bar there to reduce sound leaks. No access is needed through the shell, so acoustical experiments shall decide if the shell has openings. I'd have a truss of non-resonating material over the radiating side of the thin large soundboard as a mechanical protection, and to make stronger and stiffer this part of the harp's frame stressed by the strings. Its holes let insert the strings. Closing the cross-section between the strings would help mechanically. A cover, removed to play, would protect the soundboard further. The soundbox can be narrower than presently, which helps the transport. Consider foldable or removable pedals and feet. Inverting the neck, with the strings at right side, may make the harp even thinner. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

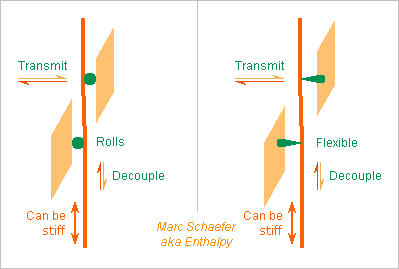

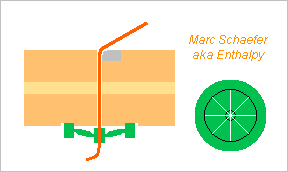

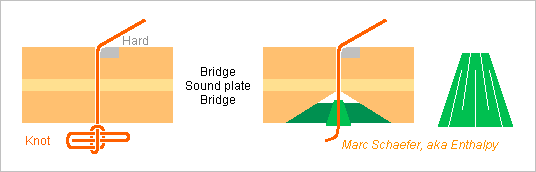

Strings can be fastened at the bottom of the soundbox, and the extra length be stiff, if the contact with the harp's soundboard decouples the vertical movements and transmits the horizontal ones. The left attempt uses rolls. These must move with the slightest force, which isn't trivial and may exclude any sliding guide. It also demands a smooth sleeve around the spun strings. The right attempt has flexible parts. These must stay horizontal when tuning the string: glide easily, small zigzag. Notches guide the string transversally in both cases. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

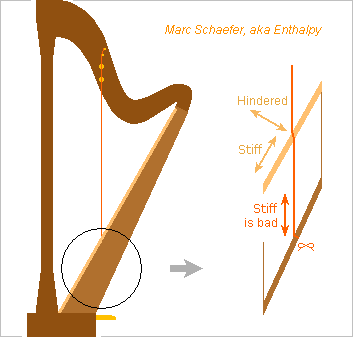

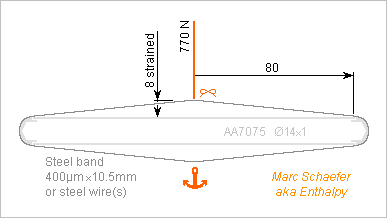

I confirm that strings fastened directly at the bottom of the soundbox are too stiff, hindering the soundboard's vibrations. Good reason not to do it up to now. The tension of the metallic bass strings bends present soundboards visibly, by >1mm, but 600N on 250mm extra length of a string with D=1.1mm steel core stretch it by 0.8mm only. This vertical stiffness added to the in-plane stiffness of the soundboard would hinder the perpendicular vibrations. The extra string length needs elasticity. I didn't check if the gut treble strings bring enough elasticity naturally. ========== This spring example gives elasticity to the string extra length and adds little mobile mass. Meant for an Eb=78.1Hz string, 1.27m spun metal, 770N tuned, 19.6g/m. 3850N tension in 400µm*10.5mm L=80mm cold-rolled steel (possibly split in two to pass the string, or replaced by steel wire(s), D=2.2mm cold-drawn) strain it by 0.35mm, contributing 2*3.5mm at the string. The mass is 4*2.6g, acting as 3.5g at the string. If someone can solder high-carbon steel, fine; if not, the band ends can be clamped together with many screws, or maybe a wedge. 7700N compression in Do=14mm e=1mm L=160mm AA7075 tube strain it by 0.42mm, contributing 4.2mm at the string. The mass is 4.1g, acting as 1.0g at the string. 11mm strain is more than a soundboard's deformation presently. 4.5g mobile mass is less than 40g per string for a present soundboard that needs 20mm wood to stand the traction. With that spring, a lighter soundboard looks possible. ========== Can the spring be lighter? The Lambda shape of strong material is a good start: as in a longbow, it's light and uses at a lower speed an elastic material that can be heavier. The Lambda is lighter if less flat. Cascading several Lambda brings the slowing factor. If the Lambda don't bring enough elasticity, the added elements (a tube previously) can be nearly immobile to add less inertia to the string. ========== I had imagined that the soundboard's deformation could cause most detuning, but after seeing experimental data about polyamide and gut strings, it's less clear. Elasticity created by metal parts could maintain a more constant tension in polyamide and gut strings when these lose stiffness at heat. The tension drop might even be adjusted to compensate the reduced mass of the speaking length. Springs are then useful for medium and treble strings too, even if the extra length is elastic enough, in which case the springs can be heavy. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Materials

One musician confirms that his French system bassoon reaches high notes easily Pw3WcvcJslQ on Youtube he demonstrates an E, one octave higher than the Sacre du printemps, 4 octaves and a small fourth over the lowest Bb. Or if you prefer, near the oboe's conventional limit. The narrower bore of the French system surely helps. The reeds are a bit smaller too hence faster, but I doubt they limit the instrument. The tone holes differ, obfuscating the comparison. And Buffet Crampon still uses dense wood Bassoon model at BC presently Dalbergia Spruceana (amazonas palisander, amazonas rosewood) amazon rosewood at wood-database.com whose 1085kg/m3 and EL=13GPa are twice as much as for maple used on Heckel system bassoons. ER, ET and damping would be as significant. The video's author tells "lots of advantages" [to the French system]... except that it's even less loud than the Heckel system, and the fingerings are worse.

-

String Instruments

Violins and their relatives get a "purfling" at the rim of their table and bottom Purfling at Wiki to protect the table and bottom against cracks. Some sources add "and to ease the vibrations" despite the purfling is glued in the groove. Maybe preimpregnated graphite filaments could replace the sandwich of precious wood there. They would be stronger and much faster to install, if possible on the wood without a groove, which would ease modifications. Some clarinet makers reinforce already the ends of the grenadilla joints with graphite filaments instead of metal rings. The matrix shouldn't absorb vibrations: no polyester, but epoxy maybe, preferably warm hardened. Or can hide glue, ubiquitous at luthiers, impregnate graphite fibres? Several continuous turns of thinner filament at the table and bottom's rim would leave no weaker zone. I believe it's optically acceptable to run straight where the table and bottom have angles over the glued corner blocks; add black paint if preferred. Or cut the filament there. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy ========== In the messages on January 20, 2019, I drew the cones (displayed green) that shall hold a string much bigger for visibility. They would be as small as possible to reduce the inertia and damping. The second variant, with a single part displayed green, seems to need more mass.

-

String Instruments

At a harp, the strings pull about 10kN directly on the soundboard. The soundboard must be thick, which loses sound strength. Nevertheless, soundboards sometimes break. Could the soundboard's deformations cause most detunings at the harp? Gut strings don't detune so badly at violins, but strongly bent wood may be more sensitive to humidity and temperature than stretched gut. The other instruments do it differently. The violin family only bends the strings by roughly 1/10th over the soundboard, so the force is much smaller, and only 1/100th of the soundboard's compliance acts on the strings' tension. Strings make just a sidejump at the piano's bridge but exit parallel to their arrival, so no net force results, only a torque. I suggest to copy that. Maybe the soundboard could be parallel to the plane of the strings, but this seems inconvenient at the treble strings at least, which are very short and played with both hands. On the sketch, the strings pass through the soundboard, making just a small zigzag there, and they hold at the bottom of the soundbox. A small tube, of alumina or other hard material, probably notched, can protect the soundboard (including the bridge) from the string fed through and transmit the vibrations. A small tilt suffices, as the maximum deflection of the string suggests. Powder of graphite or MoS2 would linder the sudden tension releases, and piano bridges have a special black material for that purpose. The instrument's foot may need modifications, possibly more depth. If an added frame holds the strings' bottom, it might pass between the left and right pedals towards the column. A full-loop steel frame gives the steel-stringed piano stable tuning. I have a feeling (and didn't check as usual) that this idea was already tried and abandoned, possibly because the extra portion of the many strings (which must be precisely parallel) is too stiff and hinders the soundboard's vibrations. Though, this construction works at a piano which has more strings and where the extra portion is short too. I should come back with proposals for fast added compliance in some directions. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

Did I see that mammoth ivory makes string supports over bridges, ornamental parts of violin bows, faces of piano keys, and more? That would be the answer to the ban on elephant ivory trade. But: To my opinion, mammoths belong in museums and to science, not to sources of raw material, even if we have many mammoth remains. Ivory yellows over time and doesn't resist abrasion so well. If law changes, musicians will get trouble at the borders. Annoying now with precious wood used under older law. Ceramic can replace it in many uses. Alumina is white, comfortable to touch, hard, extremely resistant to light and abrasion, lightweight, extremely stiff, and a 30mm*30mm*1mm plate can fall on a tiled floor without breaking. Zirconia is even harder and stiffer. Parts can be sintered to accurate final shape in many cases or shaped by grinding, including with hand-held machine tools. To support a steel string over a thin wood violin bridge, a ceramic insert, sintered or ground to smooth shape, would outperform ivory. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

This variant shall hold a string without a knot too. In one part, it seems easier to use and harder to lose. Maybe it accommodates more varied string diameters, but then it's less caring with the string. The part seems heavier, undesired for the inertia and damping of the soundboard. The part must not spread against the soundboard, so graphite choppers reinforcement may be needed, or some outer ring, possily of graphite fibres. A laser can cut narrow slits. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

The concert harp has a magnificent sound, rather loud, harpists are agile, and the instrument is irreplaceable Harp and Pedal harp at wiki but it badly needs improvement: It de-tunes very quickly It is fragile but would better be louder The concert harp is still a diatonic instrument, yessir, with 7 strings per octave and pedals to raise them from flat to natural to sharp. Little hope for improvement as chromatic harps were introduced and are but abandoned. They can't play the glissandi of existing scores. ========== New strings de-tune even faster. Harpists claim that the setting of the knot they make at the lower end is an important cause. The knots take also time to make. So here's my suggestion to hold a string without a knot: (I suspect the bridge is in one part and interrupts the sound plate) To grip the string, the inner part must rub on it but glide against the outer part, which might consist of Materials produced for plain bearing bushes. They contain graphite fibres, graphite powder, Ptfe powder... to glide easily. Among them, polymers are light. A material like aluminium alloy covered with a nickel layer that embeds Ptfe powder. To help match the string's diameter, the inner part can have alternate slits, like machine tools hold some tools. A laser can cut narrow slits. All edges must be smoothened, as some strings are made of gut. Pom is easily machined and its coefficient of friction is higher, while Pa11 and Pa12 accept a big elastic deformation. One place may need several parts to accommodate varied string diameters. Alternately, several separated subparts may replace the slit one, but they are less caring with the string. Instruments use to live over a century and play with many musicians, so something is needed to avoid losing the parts, better at the instrument than separately. Some tool may help push the inner part up before stretching the string and later eject the part. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

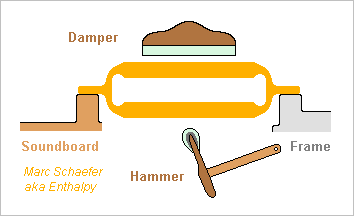

Here's a sketch of a resonator for the piano's highest notes. The example consists of a superimposed pair of bars suspended at the ends, machined in on part. Data about bell bronze is scarce and very inconsistent. Taking E=117GPa and rho=8600kg/m3 for the uns C91300, ideal bars with L=40mm and e=4mm would resonate at C=4186Hz, the piano's highest note. This needs adjustments, because the speaking length isn't so simple, and G, nu and the end stiffness mess up. Possible replacement anyway for the strings with 48mm speaking length. The width changes the direct radiation and the vibrating mass: 6mm let two bars weigh 16.5g, versus 0.7g for three D=0.9mm strings, while a usual treble hammerhead may weigh 2g. The bars can be reasonably thicker and proportionally longer at constant frequency. Where the soundboard and the frame hold the resonator, vertical stiffness lets the element transmit more energy at the note's beginning and leave less in the sustain. As the resonator is sketched, the ends move horizontally a bit. Design can improve that, or maybe the fastenings can be made to dissipate little. Partials are aligned like N2 in an ideal case, but G, nu and the end stiffness mess up. If someone believes it matters, thickness adjustments at the proper locations align the partials, even at 1:3 or 1:2. At >3kHz we're nearly deaf to harmonics and I'm pretty sure that the piano's felted hammers create none. The piano sound must result from the felt hardness, the hammer impact transmitted to the soundboard, the initial strong radiation followed by a slower decay, and a double bar can mimick all that. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

The piano's highest notes are extremely short, (perceived) too low, and just bad. As opposed, the celesta, glockespiel, metallophone and other percussions have decent high notes, with agreable sustain, and are perceived accurately and in tune. Whatever the reason for the bad piano notes, I propose to replace the piano's highest strings with percussion elements to solve both issues. Success would even allow to extend the piano's high range. The sound may differ from the lower notes' strings, but the highest strings differ already, and they're so bad that an improvement is likely. Keeping hammers and their felt should help mimic the sound of the lower strings. The controlled dampers become necessary again. A piano doesn't have any at the treble strings because these decay too quickly anyway. A switch or pedal could shorten intentionally the sustain to play pre-2019 music. Tuning differs from strings. If it's needed, it may result from drops of solder added or filed away. Detuning is expectedly small, as for most alloys Young's modulus drops by 0.2% and the resonance by 0.1% over 5K temperature variation, and Elinvar would drift even less. Strings tend to drift 10* faster, and the percussion elements won't follow the strings. The ideal procedure is hence to leave the percussion elements as they are and tune the strings as needed. ========== Simple tempered carbon steel is a good material for high percussions. Bell bronze Cu81Sn19Pb0 (uns C19300) and Invar Fe64Ni36 prolong the sustain. Superinvar Fe63Ni32Co5 may be worth a try. One possible shape is a superimposed pair of bars suspended at the ends. They can hold at the frame at one end, at the bridge at the other, be struck from below (in the case of a grand piano) and damped from the top. Small or no modification to the piano. Retrofit? The choosable dimensions can resemble the strings, reducing the modifications to the piano. The bars are much heavier than the short strings. This matches the hammers better, and whatever the damping process, it helps a longer sustain. When only the lower bar vibrates, it transmits much force to the bridge. Soon after, the upper bar vibrates in opposition, and the pair transmits little power to the bridge, prolonging the sustain. Same process as with 2 or 3 strings per note, and this hopefully produces the same sound envelope and perception. The symmetry of the bars and the rigidity of their connection to the bridge can be chosen for longer or for stronger sustain. Bars suspended at the ends have their partials in tune (like N2), in case someone believes it's useful. A drawing should follow. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

The WNG company produces piano actions made of graphite fibers instead of wood wessellnickelandgross they claim graphite improves stiffness and mass. Their argument is simplified. Laying graphite filaments or fabric for each of the 88 piano keys is unaffordable, so instead they inject a thermoplastic loaded with graphite choppers. Very nice idea for mass-production - but wooden parts too are profiled collectively by shaped tools, then just separated by a disk saw. For stiffness, 30% choppers bring only E=18GPa, far behind oriented long fibres. This table compares the stiffness of parts if dentical mass, for beechwood, thermoplastic with 30% graphite choppers, and electronickel: CFRP has no magic property. The trick, too long for commercial explanations, is that wooden parts are plain while CFRP parts are lattices or tubes as injection allows it. This can outperform wood. E p E/p3 E/p2 E/p ========================================================= Beechwood | 10G | 720 | 27 | 19k | 14M CFRP | 18G | 1200 | 10 | 13k | 15M Electronickel | 209G | 8900 | 0.3 | 2.6k | 23M ========================================================= Pa kg/m3 Plate Rod Tube Piano actions might also be electroformed. Metals outperform injected CFRP at hollow parts and lattices. Ni-Co is a vibration damper, Sn and maybe Mo can alloy Ni. Electroformed parts can be thinner and more accurate than injected ones, Ni and Co can be brazed. Time, air, light, humidity, temperature do nothing to Ni and Co parts. Fast production is less clear, but pianos don't sell like candies neither. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

Graphite fingerboards exist already for guitars, cited there MJ6iyWSEzIs on Youtube, at 1:32, no other detail about the exact material nor how it performs this task is easier at a guitar, where the strings rub on the frets, than at a violin. But at least, experience exists. ========== Graphite top and bottom plates were tried on violins in the mid-70's. The caring commentary is "interesting then, but drifted over time, abandoned". Ah, OK. Graphite sound plates exist at guitars, example in the same video MJ6iyWSEzIs on Youtube, comparisons with wood at 3:06 and 3:38, 4:14 and 4:52 and they sound just like one expects. Possibly resonances closer to an other due to the low flexural speed, and stronger as a result of small damping. While I have no opinion about guitars, I would not play a violin that sounds like this. But sandwich construction and some aramide fibres may improve the instrument. Pianos with a graphite soundboard exist presently: the Phoenix 232 for instance, hear there EBvrQlZYS-o on Youtube while it sounds generally good to my ears, some notes don't, around 0:44 (octave above A=440Hz) and 1:07(two octaves higher). Sandwich and aramide? At least their bracings look like wood. I don't notice these unnice notes at the more recent Steingraeber-Phoenix E272 rCqgpt3KGEc on Youtube, music begins at 0:07 which sounds nicely to me (and differently from Kawai and Steinway) except for the lowest notes, but that's a matter of taste. The manufacturer, Phoenix, is a partner of Steingraeber, and has a Youtube channel too phoenixpianos and their Youtube channel ========== I wanted to suggest metal agraffes on piano bridges to sustain the highest notes longer, but Phoenix has them already Phoenix agraffes and I hear no longer sustain. Saved my time.