Everything posted by Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

Here on December 30, 2018 05:13 PM I suggested to lay a few graphite fibres on the plates as bracings. I suppose the composite damps less than spruce does, but then a well adjusted mix of aramide and graphite fibres would tune the damping at will. Aramide fibres are horrible to cut. The mix offers more tuning possibilities than wood, nice. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

Do a violin's table and bottom radiate efficiently? I try to estimate the radiated power from the vibration pattern on Martin Schleske's fantastic website: schleske.de For instance at the 409Hz resonance, the vibrating zones are ellipses about 100mm*50mm. Lambda/4=209mm, so the 5.6mohm*F2=0.9kohm radiation resistance of a small source isn't too wrong here. Average arbitrary 1m/s rms in one such zone pushes 4dm3/s air to radiate 14mW rms. The zone's mass, about 3.5g, takes 9N and reactive 9W to accelerate. Radiation contributes 0.15% to 1/Q while losses are 1.5% in Schleske's measures. At 884Hz, the small source resistance would be 4.4kohm but the observed individual zones are about 100mm*60mm while lambda/4=97mm so the resistance would be bigger. Though, the pattern is a quadripole, 75mm=0.19*lambda and 160mm=0.41*lambda, and the 0.19*lambda reduce the individual resistance. I just keep the 4.4kohm per zone, should be good enough for the qualitative conclusion. Again 1m/s lets each zone radiate 98mW and absorb reactive 30W so radiation contributes 0.3%. At 2060Hz, the zones are about 60mm*45mm but lambda/4=42mm so the small source's 24kohm and 0.1W are less wrong than a wide piston's 0.9W, while the multipole's spacing of 70mm=0.42*lambda changes little. Each zone's 1.9g absorbs reactive 25W so radiation contributes 0.4% while losses are 3% as deduced from the resonance peak width. Picea abies' (spruce) reported losses are typically 0.8% lengthwise at acoustic frequencies. Luthiers seek exceptional wood and excel at avoiding other losses. The violin's table and bottom radiate rougly 0.1* the power received from the strings. That's better than expected but it would usefully improve. It's my reason to seek lighter tables and bottoms, with bracings. A pizzicato sound is much shorter when pressing the string against the fingerboard than with an empty string. This tells that the finger (and fingerboard) absorbs most of the string's power, even before the power has a chance to reach the table and bottom. But an instrument with frets would not be a violin. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

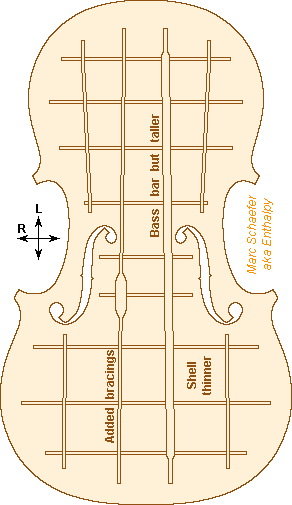

Instruments of the violin family have arched tables and bottoms. This brings stiffness at precise locations with no added mass. Could bracings replace the arched shape?. This works for the guitar, whose table is flat and 1mm thin, a value that would be difficult to attain by carving arched plates but is usual for flat material using industrial tools. The higher pitched violin would need bracings stiffer than the guitar, and stiffer than in the previous estimate whose plates are arched. If the spruce table is 1mm thin, a typical distance between bars drops to <30mm, and the bars are taller - to be experimented, for instance with Chladni patterns, possibly after varnishing. Reinforcements seem necessary at the plates' rim, continuous but possibly of several overlapping glued parts - or shall all bars and the rim but shaped from a single plate? The instruments needs also taller ribs to keep the volume, and a taller bridge to give the bow a way. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

I suggested in this thread on December 16, 2018 06:30 PM to add bracings to the tables and bottoms of the violin family, to make the plates thinner, lighter, and hopefully lounder and more responsive. The thinner shell adds resonance modes between the bars, so these must be close enough to eject to modes to high frequencies. A violin can play more or less a B at 3951Hz on the fingerboard (a bit higher by playing so-called harmonics): the lengthwise flexural half-wave in 1.5mm thin spruce is 40mm, and this shall be the distance between the bars. Irregular spacing helps further. For comparison, a guitar table is 1mm thin. ViolinBracings.zip This spreadsheet computes the EI/rho of plain wood (spruce for the top plate) and a thinner shell with bracings. To obtain the resonant frequencies of 2.5mm plain spruce from a 1.5mm shell, 1.1mm thick and 3mm wide spruce bars spaced by 40mm suffice in the R direction (they ar cut from the stiffer L direction), while those stiffening the L direction are 2.4mm thick. The resulting table would weigh 0.70* as much as plain 2.5mm. The plates' curvature adds stiffness, hopefully in the same amount with thinner shells and bracings. The bars stiffening the R direction could be cut thicker from the R direction to keep its damping. A CNC milling machine could carve them from thicker wood together with the shell in one part, much like isogrid construction in aluminium. A few preimpregnated graphite fibres laid on the shells' inner faces might replace the added wood bars, but their damping differs and they seem more difficult to adjust. The sketched bracings are by no means an optimum nor the only possibility, as guitars show, and they will need adjustments beyond a spreadsheet's possibilities. At best, they may guide the first experiment, to check if the idea has potential. Since violin-like instruments alternate the resonances among the top and bottom plates, both plates should be modified to keep the balance. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

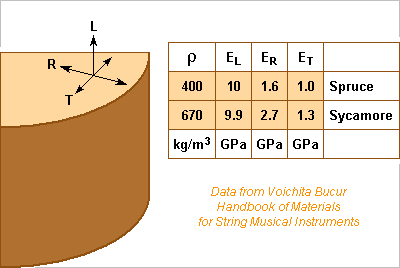

Many string instuments use Picea abies and Acer pseudoplatanus (Norway spruce and sycamore) Picea abies and Acer pseudoplatanus on wiki for which Voichita Bucur and other sources measured the elasticity: Data spreads much, as expected from a natural material. The experiments need careful interpretation, as for instance the small shear modulus can reduce a beam's flexural stiffness. Elasticity must also depend on the frequency, so static or ultrasonic data may be inaccurate for music instruments. Good news: all the sources I've seen agree on the axes L, R, T. Attempts are reported from time to time to replace wood by man-made materials: aluminium, graphite fibres, 3D printed polymers... Wood outperforms them by far because it propagates flexural waves faster, as is known to instrument makers and to academic researchers. For a given resonance mode, faster waves enable a bigger soundboard that radiates better. Or at identical wave speed, the soundboard can be lighter to couple better with the strings. Also, when flexural waves are faster than pressure waves in air they pass efficiently to the air; this happens above a frequency reached earlier with wood. The equation for 1D flexural waves is (2piF)2*rho*e = k4*E*e3/12 where the wave speed and the soundboard's mass depend on E*e2/rho and e*rho for which Picea abies brings EL~10GPa, ER~1.6GPa, rho~400kg/m3. Compare with aluminium alloy: E=72GPa rho=2740kg/m3. To match spruce's flexural wave speed in the L direction, aluminium would be as thick and 6.5* as heavy, ouch. To match the R direction, aluminium would be 0.4* as thick and 2.6* as heavy, yuk. So what about graphite fibre composites? They can achieve rho=1550kg/m3, EL~150GPa, ER~20GPa: to match spruce's flexural wave speed, graphite would be 0.5* as thick and 2.0* as heavy. So while graphite fibres may compose some day the radiating body of a good string instrument, they can't mimic a spruce or sycamore soundboard. Sandwich construction may be the path to fast flexural waves. Or the radiating body better uses compression waves somehow. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Materials

Trying to imitate the allegedly stiff but lighter wood grown during the Maunder minimum and used for bowed instruments by Guarneri, Stradivarius and Guadagnini, researcher let fungi consume some components of Acer pseudoplatanus (sycamore) and Picea abies (Norway spruce) researchgate.net with varied effects on the density, Young's modulus and damping, depending on the wood, fungus and duration. While the effect on bowed instruments remains to see, damping *1.5 to 1.8 could improve bassons and contrabassoons built of Acer pseudoplatanus, easing the high notes. In figures 4a (axial) and 4b (radial), page 8 of the Pdf, 6 weaks chewing by Xylaria longipes reduce E by 17% but rho by 8%, which is a limited drawback for a bassoon and can become an advantage if building and constant mass, that is thicker. I wondered why players of Heckel-system bassoons found high notes difficult while I achieved the conventional high G after one week. The narrower French system surely helps, the hard reeds too, but the denser harder wood may very well ease the high notes. My 1915 instrument, as thick as recent ones and heavier, is probably of Dalbergia latifolia (rosewood), twice as stiff as Acer pseudoplatanus. Merry Christmas! Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Quick Electric Machines

Yes. On the other hand, I just compare what can be done with the existing stuff. Tugplanes presently in activity were designed 50 years ago and built 40 years ago. No newer design with a combustion engine replaced them, despite fuel to operate these antiques costs a lot. So to imagine if an electric tugplane has a chance on the market, I compare it with with the present fleet, rather with an alternative inexistent option. Pessimism would let say that if newer thermal designs didn't get through, the electric one won't neither. But an electric tugplane has some advantages. If willing to compare a new electric design with a new combustion engine design, we might forecast that power is 3* cheaper with electricity, maintenance is much faster, and construction looks cheaper (far from obvious, because combustion engines are often modified car engines). But this is only extrapolation and gut feeling, as neither one nor the other exists.

-

String Instruments

Guarnieri, Stradivarius, Guadagnini... Soloists prefer old instruments from these luthier for the strong sound, shrill timbre that gives "projection", and easy response, while orchestra musicians may prefer a warmer sound. Many theories have been proposed about these old instruments, the lacquer is less in favour now, the wood is more fashionable pnas.org , nagyvaryviolins.com , (in French) guillaume-kessler.fr where the decomposition of hemicellulose is considered, as well as rotting in a lake before processing, and more. These suggest a loss of material that would make the wood lighter, propagating flexural waves faster, or rather allowing for the same resonant frequencies lighter soundboards with an easier response. At least lighter tables and backs would be possible with usual luthier wood while keeping the resonant frequencies. Just make them thinner, and stiffen them with more bracing like the guitar has, instead of the sole bass bar on bow instruments violin construction and guitar bracing on wikipedia Of course, this needs a complete redesign, at least of the bracing. Maybe one bass bar (at the back too), taller than presently, and several transverse bars, not as tall as the bass bar but linked firmly to it. A guide would be to compare the resonant frequencies of the table and back with a good instrument and adjust the bracing to match them. Immediate display of the nodes and antinodes would help a lot, since adjusting and replacing a bracing element is fast. For that observation, I believe the rim should better carry some reasonable extra mass, rather than floating free. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

Hello everyone and everybody! Some string instruments have parts, notably a fingerboard, commonly made of ebony: some Diospyros species, sometimes a Dalbergia species Fingerboard , Ebony , Diospyros , Dalbergia on wikipedia Ebony has drawbacks: the trade and travel of many Diospyros and Dalbergia species is restricted, even as components of an instrument; it takes many years to dry before processing; and it's expensive. Replacements were proposed, including hard rubber "ebonite", which has only 1/10th the stiffness of ebony and maybe not the resistence to abrasion. My suggestion is a polymer loaded with short graphite fibres with random orientation. They are hard and stiff (1/2 to full ebony lengthwise Young's modulus, transverse outperforms), some resist abrasion in plain bearings, they slip well and feel soft. Many are readily available, like POM and PEEK. Turning and milling tend to blunt the cutting tools quickly, faster than metals but slower than aramide fibres do. I suspect sanding roughens their surface, while planing and scraping have better chances. Worth a try? Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Materials

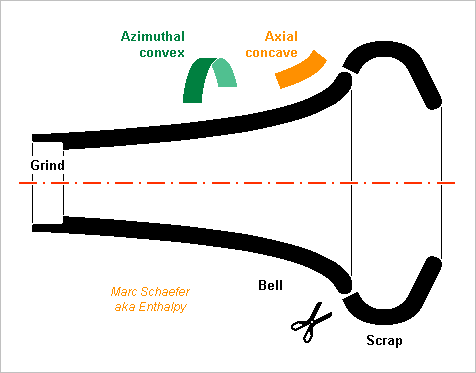

This is how filament winding can make a bell, bocal or other part, at least in my imagination. Illustrated here with a bell of axial symmetry, for which turning is possible, but it applies to asymmetric shapes too. The preimpregnated filament is wound on a mandrel, usually by CNC, then polymerised. Bells are concave along the axis but convex along the azimuth, so some winding angle puts the filament on a convex path, where the mechanical tension presses the filament on the mandrel, as usual too. The filaments can't end at the flare's rim because they would slip on the mandrel, so a bigger part is wound that converges at its end. The excess portion is cut away: turned or ground or somehow. Here with axial symmetry, the scrap part can be cut at it maximum diameter too and removed to reuse the mandrel. More complicated shapes, like bocals or bass clarinet bells, need to melt the mandrel away, which can be of low-melting alloy, maybe of talcum-loaded paraffin, and is cast for each bell. The rim can get a protective or aesthetic part, and the fitting is typically turned, milled or ground. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Quick Electric Machines

Thanks for your interest! There are a few biasses in my comparison. Tugplanes used presently were designed >50 years ago while I compare with a more up-to-date design and modern materials. They are too big: most accommodate 4 people while only the pilot is needed there to tow a glider. They are too fast: meant for >200km/h or more while towing is done at 110km/h. So my comparison is unfair in that the reference is unfit for the job. Or said differently, I compare with the existing stuff, not with what a new, specialized combustion engine tugplane could achieve. Other comparison elements are more fair. Conversion from electricity to shaft power is >95% efficient, but from fuel it's rather 40% (or less with the old engines), giving an other 2.5* advantage to batteries, over the 2* you mentioned. Then, piston engines that power the existing tugplanes use aviation gasoline, not jet fuel. With high octane rating, low water, formulated with lead for old engines, Avgas 100LL costs typically 2.5€/L here in ol' Europe, ouch. The tugplane's descent contains almost 1/2 the energy put in the ascent, so maybe 1/3 or 1/4 can be gotten back to the battery. A turbine sized for small aircraft would use cheap jet fuel, but presently small turbines are rare and demand a special license. A Diesel engine could burn jet fuel and be less inefficient than the present Volkswagen and Lycoming that are 0.5 century old designs - several aviation Diesel were under development 25 years ago. Maintenance is costly with a piston engine and nearly unnecessary for an electric motor. The battery must be kept under surveillance, but electronics does it for free. Fill less the tank: in my estimate, I wanted a battery 5* bigger than the minimum, because the pilot wants the capability to wait in the air or join an other airfield if something goes wrong. That would be the same with a fuel. So while I didn't check how good a new design with a combustion engine would be, the usual comparison is that electricity (at the present taxes...) is easily 3* cheaper than gasoline for the same flight and design epoch. ---------- Battery cost: I had feared a replacement every season, due to the very frequent charges and discharges. The estimated 10 years lifespan that result from shallow discharge are a relief to me. ---------- Silent propeller: this is a recommendation, not a consequence from the electric motor. I should have made it clearer. Once the motor is silent, most noise comes from the propeller, which shall bear the emphasis. The first standard means for that is a more solid propeller, with more blades, wider. This goes in the good direction for regenerative braking. The other means is to bend the blade tips backwards.

-

Quick Electric Machines

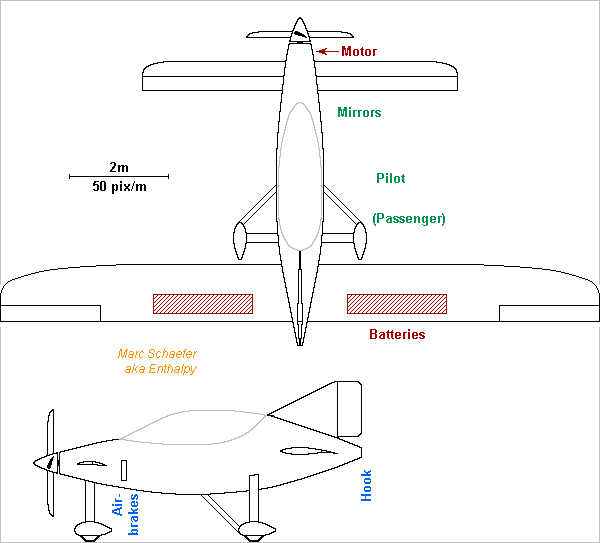

A battery-powered aeroplane can tow airgliders. Towing is the major cost of a glider flight, as the aircraft used presently are too big, designed for a higher speed, and consume lots of expensive special gasoline. Batteries power the very short flight easily and use cheap electricity. The market isn't huge, but an electric tugplane is simple to design and build, its use saves much money, so it could be a first commercial success for electric planes. The typical flight profile is to manoeuvre on the runway, wait for operations on the cable and the glider, take off, climb in <5min to ~800m, release the glider, plunge to the airfield and land. Some Li batteries are designed for quick charge and discharge; I take data from Saft's VL25PFe, safer thanks to Li-phosphate and efficient enough here: 28Ah, 0.94kg, 360kJ/kg, 1700W/kg (yes, 200s). They show the feasibility but are not an optimized choice, nor did I check the availability and price. 300kg batteries provide 108MJ and up to 510kW. Electronics, a geared motor and the propeller convert just 120kWe (163HP) to 90kW traction. Neighbours would appreciate a silent propeller. Several features shall avoid messing with the towing cable. The bigger wing at the rear shall counter vertical forces by the glider better. An additional rudder can fit at the bottom. The design has a fixed landing gear and no landing flaps for safety and cost. 35m/s operation and 25m/s stalling permit the 44kg/m2. The D>1.9m propeller pulls 2.6kN at 35m/s frame speed. 350kg frame, 300kg battery and 100kg pilot total 750kg tugplane flight mass. Climbing at 5m/s with a 600kg glider takes 1.9kN, moving the L/D>35 glider 0.2kN more, leaving 0.5kN to move the tugplane, for which L/D>15 suffices - the aspect suggests L/D>25. 30s equivalent full-power of ground operations and take-off, then 160s climbing, use 23MJ or 21% discharge depth at 4*C pace, sparing the batteries meant for 17*C. They should last >15 000 cycles or about 10 years; that cost remains to check. Electricity costs only 2€ per cycle. Regenerative braking by the propeller would be useful. A 100kW cable must be brought to the runway. 85MJe left after towing can still fly the tugplane for 130km and 1h at L/D=15, or rather 220km and 1.7h at L/D=25. That's important for safety, and to convey the tugplane, and for secondary uses. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Materials

The rare alto and tenor tárogatók have a curved metal bocal that fits in a mouthpiece with wider end bore like the saxophones do, instead of fitting outside a mouthpiece with narrower end like the clarinets do. As opposed to the soprano tárogató that uses clarinet (-like) mouthpiece and reed, they must even use bocals, mouthpieces and reeds from alto and tenor saxophones, leaving even a chamber in the mouthpiece. One tenor can be seen and heard there: pn6X4vvbbz8 on youtube at 12min Logically, the alto and tenor don't sound like the soprano tárogató, but very much like saxophones, hence are little useful. Already Stowasser used saxophone-like alto and tenor bocals: I suggest instead that the alto and tenor tárogatók receive bocals that fit on the mouthpieces of alto and bass clarinets, and use corresponding reeds, to achieve the distinctive sound. ========== All low wooden clarinets and tárogatók, beginning with the altos, have their curved parts made of metal. Though, a wooden bell is claimed to give the bass clarinet a "more powerful and centred sound": wMbK_zhcmOk on youtube at 2min16 so graphite composite may improve the bells and bocals of clarinets and tárogatók. While injection needs a costly mould, filament winding companies would easily produce a bocal shape. A U-turn and a bell may need several parts. I suppose a low-melting alloy can make the mandrel, cast for each part and molten away. Paraffin loaded with talc makes great mandrels for glass web, but may be too weak for graphite winding. Graphite fibres don't, so the matrix must dampen the vibrations. Epoxy doesn't. Whether ABS, PP or polyketone can impregnate the filament? Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

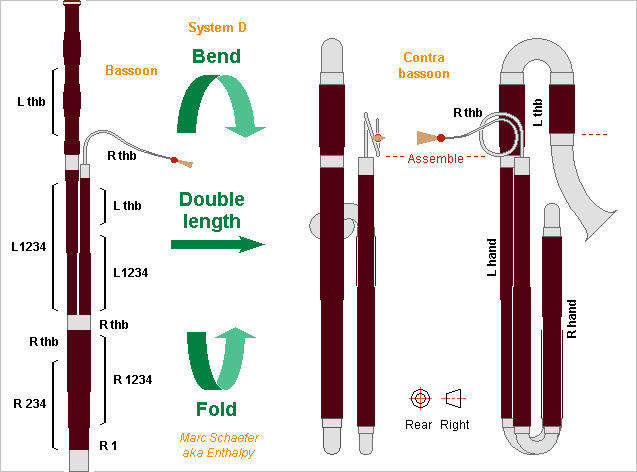

Woodwind Fingerings

Here's a system D contrabasson, bent at the bell to be less tall. What would be the boot at a bassoon is folded to the front for compactness. Disassembled, it fits in a manageable case. The right and left tubes could very well be swapped so the left fingers' tips reach between the tubes to make simpler keys. Only the two low B and Bb keys cross an assembly line, plus the hypothetic register keys at the bocal. All tone hole covers can be at wooden parts, and the bell and U-turns are passive. Some strict woodwind manufactures should find it easier. But the bell, turn and two nearby cylinders can be one metal joint. The metal walls could be electroformed as already suggested Jan 01, 2018 and May 02, 2017 and nearby while graphite composite might perhaps replace wood too if the polymer matrix dampens enough (polyketone? Abs?) Nov 01, 2017 and followers Whiskers-loaded polymers can be machined similarly to wood while filament winding can make bent shapes Nov 01, 2017 Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

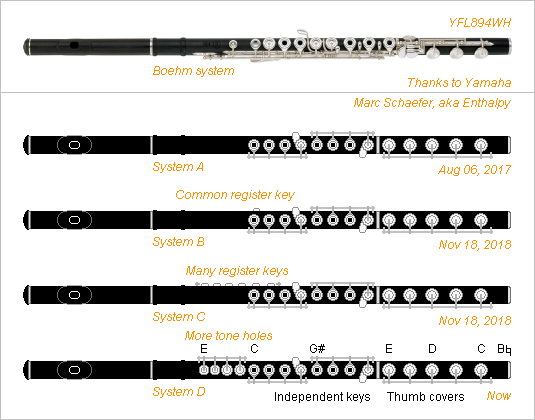

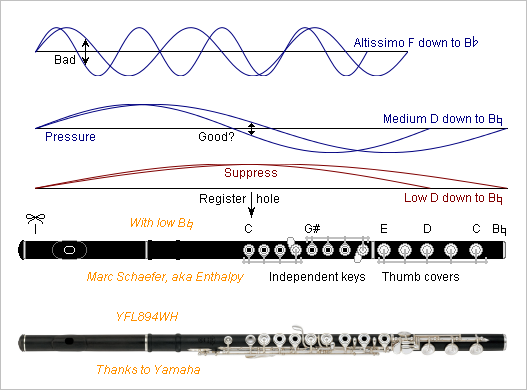

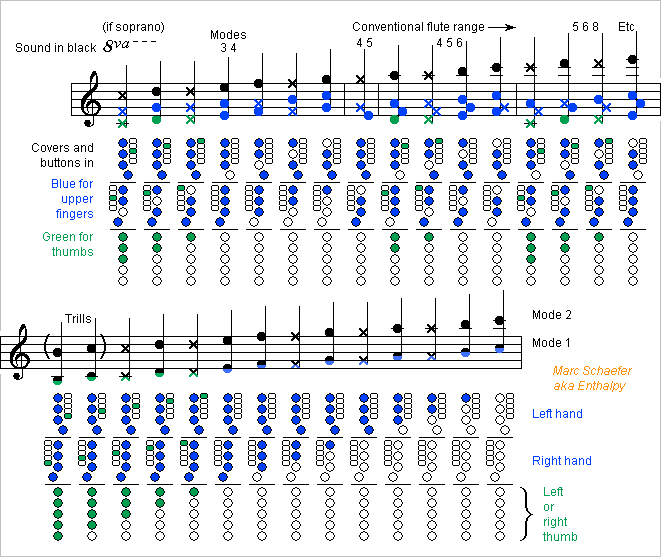

Woodwind Fingerings

This shows flutes with four systems, three already described and one coming here, retroactively named A B C D: The differences reside high at the main joint. ========== The D flute system has four tone holes above the left hand, without overlapping due to other trills and octave switch, and moved by both thumbs. True tone holes high at the main joint shall emit altissimo notes easily, 3 or 4 fork holes too. Though, the additional big holes may increase the losses at other registers. Maybe the bore can be slightly wider for balanced improvement everywhere. I've drawn the added tone holes aligned, consistently with a rumour about losses, but the keys would be simpler if at the tube's side. I ignore which system is better. At least, they're very similar, so trying them is a smaller effort. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Fingerings

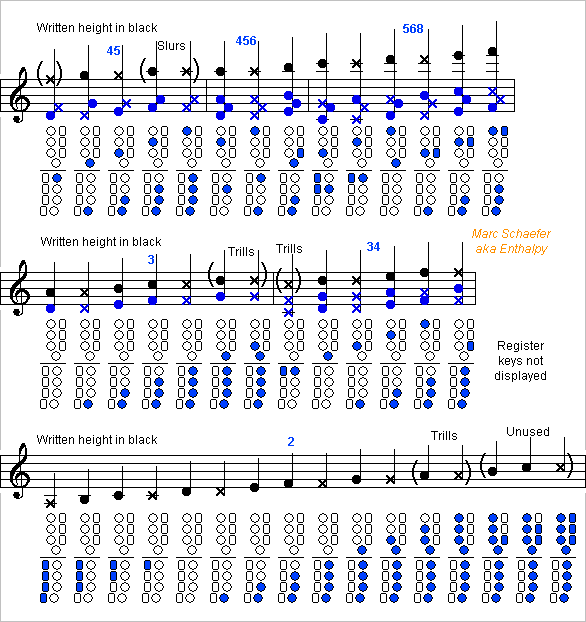

The Nov 10, 2018 flute system can have a common register key for the medium B, C, C#, D but not for the altissimo Bb to F - at least according to my figures. From altissimo Bb to F, the pressure node just right of the lip plate moves too much. The flute's pressure node pinned near the embouchure worsens this, a reed eases it. As the extreme notes create more pressure under the register hole, losses increase. It would need more holes, each for about 3 notes like the bassoon has - not quite seducing. For medium B to D, the common set of register holes would be just below the left index' C cover. Maybe the index can manage them too as at the oboe, especially if the holes reside in the cover, but I prefer a long button at both thumbs, along the buttons for B to D. If the set of holes is 14kH inductive (I take V similar to Pa and A to m3/s), at 539Hz in the medium register the two half-colums must compensate it by 2*3.2pF or 2*1.6mm of their length. That's 0.5% detuning which the instrument design can compensate. Widening the low joint would be fantastic if this reinforces the low notes. I take holes 8mm long because I imagine shorter ones would increase the losses unproportionally when playing forte. If I'm wrong, have fewer shorter holes. Drill bits exist for D=0.3mm so 10 holes make the 14kH. Many small holes increase the losses at identical inductance to suppress the low register better. This may be new. The oboe has a slit for that purpose. A laser machine, preferably pulsed, can cut deep slits. The pad should cover all holes directly, as a chamber below the pad would create damping at some frequency. Against moisture, a thin water-repellant layer may help. The basoon has already a narrow long "whisper hole". The tone holes increase losses, maybe processes still unknown too. Without them, radiation, viscosity and conductivity losses for arbitrary 1Pa (all rms) antinode pressure in a bare cylindrical L=632mm D=19mm air column are * 1.5+5.5+2.6=9.6nW at medium 539Hz; * 0.4+3.9+1.9=6.2nW at low 269Hz. The 75mm2 set of 10* D=0.3mm L=8mm register holes increases the losses when open, hopefully enough for a stable and pure second mode: * at 539Hz and 0.27*1Pa hence 8.1mm/s flow, by 0.25nW or +3%; * at 269Hz and 1Pa hence 60mm/s, by 9.9nW or *2.6. On a flute with low B, the medium D may not use the register hole, which can be more specialized and efficient. ========== A seducing alternative would add at both thumbs 6 smaller keys like the left index has at the Boehm flute. Small holes increase the instrument's losses little. These would be at perfect locations and serve also for the altissimo register. 11 buttons at the thumbs, enough to make bassoonists happy. Pressing twin buttons with a thumb eases the fingerings, and the many open holes at perfect locations ease the altissimo register emission. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Fingerings

The more recent automatic cross-fingerings I described here on May 14, 2018 and Jun 03, 2018 open four or more adjacent holes at the main transition, and open 1 or 2 fork holes early in the high register. So would these automatic cross-fingerings suffice for a flute, which badly needs them? I doubt it. At system C, overcrowding imposes smaller direct holes at the upper end. This is bad for the timbre there and for the ease of the highest notes. At system D, the many consequent holes increase the acoustic losses, undesired. Would CAD drawings and trials bring a good surprise? I'm not optimistic for the flute.

-

Woodwind Fingerings

Here's a system with simple keyworks for the Soprito, the piccolo reed instrument that plays on its higher modes, about a seventh or octave higher than written. This system has only one tone hole per halftone position and independent keys. Most fore fingers operate two buttons and covers. The covers are closed at rest except the four lowest, so the musician lowers fewer fingers, which eases cross-fingerings. The fingers can operate the button pairs at different phalanges or both with the tips, as suggested there https://www.scienceforums.net/topic/107427-woodwind-fingerings/?do=findComment&comment=1060629 experiments shall decide. The thumbs move no cover but about four duplicated register keys not displayed on the drawing. These fingerings are expectedly as difficult as the flute's one. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Fingerings

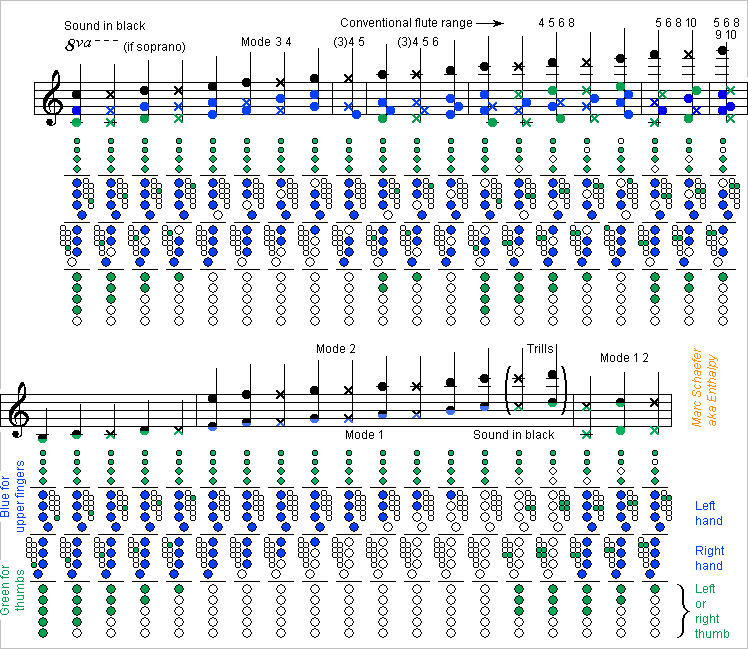

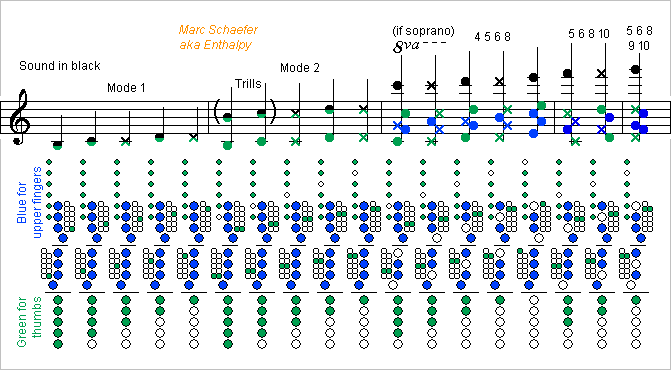

Most concert flutes have a low natural B presently so my system must have it too. Rather than adding an optional sixth synchronized cover at the foot joint, it's better to shift all keys and fingerings a halftone lower and have the low B on all instruments, as it serves for trills. Here's the fingering chart, updated from Jul 02, 2017 here: All qualities are kept, including easy slurs and trills using the standard fingerings on both lower octaves, and perfect cross-fingerings for all notes, including the third octave F#, G#, Bb, B and further in the fourth octave. The 7th and 9th modes could be added. Maybe we can have a register key for the first five notes of the second register. With its long button along the five thumb buttons for simultaneous use, and a tiny hole. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Fingerings

This is an example of a hand rest on a flute, gratefully pinched from the bass YFL-B441 For the systems I propose, where both thumbs must move freely, it can inspire both hand rests at the flute. Some non-horizontal instruments may need an adapted shape.

-

Woodwind Materials

Data about materials' internal damping is scarce, especially for the frequencies and strains common in wind instruments. In P2Q2=E'Ik24*psi2, Q may be 50 for a damping metal, P=500Pa for a flute hence P2=50Pa for the elliptic deformation near the tone holes as computed here scienceforums on Nov 26, 2017 and k2=210rad/m for a D=19mm tube, so E'Ik2*psi2=P2Q2/k22=0.057N*m/m, and for a 0.45mm tube, the strain is 17ppm and the stress 1.7MPa (0.25ksi). The strain is much smaller for the resonances that bend the tube. It's stronger for a saxophone and with materials that damp less like brass or German silver, and it's much weaker for thick wood walls. Resonances at 100Hz to 5kHz matter more to music instruments. ========== For wood, Mankind has the already cited PhD thesis by Iris Brémaud (in French) https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00548934/document with a table of stiffness, damping, density on p117 (Pdf p141). Measurements were done by resonating a 360mm*20mm*20mm beam, hence at a meaningful frequency. I wish data existed for bending across the fibres, which determines the elliptic deformation of woodwind tubes. Tan=0.57% for Dalbergia melanoxylon isn't much, but thick wood is stiffer than metal against elliptic deformation. ========== The Dtic 486490 document compiles many sources, reproduces curves and data for varied materials, and is openly available (thank you!) http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/486490.pdf Copper and its alloys, including cupronickel, brass and bronze but not German silver, are on p72-76 (Pdf p98-102). Damping is very small, 10-4 to few 10-3, and its dependence on temperature and stress suggest it's even smaller for an instrument's tiny stress. The shape memory alloy Cu Al12 Ni5 Mn2 Ti1 measured in Dtic A218801 damps strongly but seems difficult to use at music instruments. Silver, pure and alloyed with Cd, In, Sn but not Cu was measured in "Internal Friction and Grain Boundary Viscosity of Silver and Binary Silver Solid Solutions" by S. Pearson and L. Rotherham the already cited Dtic 486490 reproduces the curves on p102-103 (Pdf p128-129), where damping is very small at these very low frequencies. Obviously "sterling silver" differs to sound poc-poc at flutes. Whether the usual copper makes the magic, or something else? The high-damping Mn-Cu alloys, especially the M2052 Mn Cu20 Ni5 Fe2, was measured against amplitude and frequency, there https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/matertrans/42/3/42_3_385/_pdf/-char/en Fig.4 tells tan=3,7%-2,2% at 200Hz-5kHz and 20ppm. Excellent, but the alloy corrodes, and annealing can't restore all the damping after >5% cold deformation. Many Co alloys like 20Fe, 23Ni, 28Ni or 35Ni show high damping on p69-72 (Pdf p95-98) of the already cited Dtic 486490, but this demands a strong strain of 10-4. Worth a try, especially at saxophones? Co-Ni is easily electroformed to intricate net shapes, annealing should achieve the shown properties. Mo should be easy to co-deposit, Fe too, see here scienceforums on Sep 29, 2018 2:24 pm a magnetic field <40kA/m (<500 Oersted) ruins the damping, and wide thin parts concentrate the 30A/m geomagnetic field. This isn't extremely critical, and maybe some alloy has a low permeability, or if a layer of Co-Ni is deposited on a core, it can be interrupted at short intervals, and a pattern like zigzag still give stiffness. Some thin layer, usually Ag, can protect against contact allergies. Sharp grooves perpendicular to the strain, like from rough sanding, would concentrate the stress and increase the damping. Cheap to try at least. ========== I tried to reproduce by software the ting and poc I heard long ago when tapping flute headjoints with a small plastic part. Here TingPoc.zip TingPoc_A_GermanSilver.wav plays an exponential decay of 100ms, 80ms, 60ms at 3100Hz. I feel 80ms reproduce the German silver sound, telling Q=800 and 1/Q=0.13%. This includes damping by sound radiation and by viscosity. TingPoc_B_SterlingSilver.wav decays with 50ms, 20ms, 10ms, 5ms, 2ms at 2300Hz. With 20ms I still perceive a duration, so sterling silver must decay with 10ms at most - I didn't even hear a height, so it may have been much shorter. Viscosity and radiation are identical, so sterling silver itself brings Q<=70 and 1/Q>=1.4%. The softer shock on silver didn't prevent ringing, I believe. The ratio of yield strength, 120MPa vs 500MPa, is too small, and the plastic clapper was soft. It would be interesting to try with the Pcm alloy. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Materials

Oops. In my last message, paragraph " With the resonances ..." please read 5*10−13m3, sorry.

-

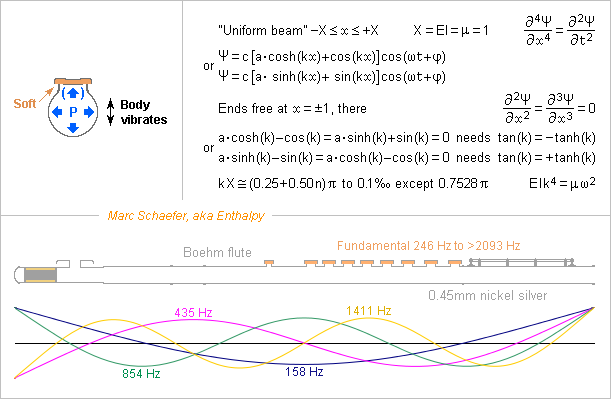

Woodwind Materials

Flexural resonances of a woodwind body, quantitatively. Here for a Boehm flute, of 0.45mm German silver (Cu-Zn-Ni alloy), with B footjoint. ========== I model the body by a uniform cylinder. µ=0.31kg/m, 30% more than a naked tube, to include the stiff parts of the keys. EI=183N*m2. The cylinder has proper flexural modes at 158, 435, 854, 1411, 2108, 2944, 3919, 5034 Hz and more. This is within the fundamental and low harmonics range of the flute. The heavy cork could be represented by extra tube length, or better, its lumped mass included in the model. The tone holes reduce the stiffness. The joint fittings are supposedly less stiff. So the evaluated frequencies aren't accurate, but the result stands: resonances in the playing range. ========== The covers move by estimated 0.1mm when the musician varies the pressing force by 0.5N (from 50gf to 100gf) so the pads are 5kN/m stiff. The covers weigh estimated 3g, so at the Eb and Ab holes they resonate around 200Hz, and above that damped resonance they behave like a mass. The other covers are pressed down by fingers that add mass and the resonance is lower. So for all the tube resonances within the playing range, the covers transmit to the tube little of the oscillating force exerted by the air column's pressure. The covers don't balance the force exerted directly on the tube. The tube receives a net lateral force. As well, the pads are far less stiff than the tube. A side force at a second mode's antinode bends a beam 123+123mm long which is 1.2MN/m stiff. The pads can at most limit the tube's resonance. ========== For instance the third bending mode around 854Hz has a half-wavelength of 93+93mm so it's 2.8MN/m stiff to a force at an antinode. The flute has two covers near both antinodes of the bending mode and the air column. In front of two D=13mm holes, 1Pa pushes 0.27mN which would move the tube by 95pm without resonance. As the covers don't follow, the tube's movement adds pulsating 2.5*10-14m3. We can compare with 0.42m air column containing 120cm3 where the 1Pa induces 4.2*10-10m3 compression as a mean over the arches. With the resonances, the effect is significant. Just Q=20 for the metal (damped by the pads, the hands and more) produces 5*10-14m3 instead, and at the resonance it's a loss rather than a capacitance. If the other losses at the air column leave it Q=200, the tube's vibration drops it to Q=160, a significant and perceptible difference. ========== Silver, while less stiff than German silver, damps the vibrations far better. If tapping a headjoint with a light plastic part, it sounds "poc poc" instead of "ting ting". This reduces the tube's vibrations hence steals less power from the air column's resonance. According to this model, a silver headjoint brings some damping to a resonant main joint. But to a silver main joint, the headjoint material matters little, as I observed (here on Nov 07, 2017) http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/111316-woodwind-materials/?do=findComment&comment=1022242 Silver keyworks damp their own resonances, which must be excited by the tube's transverse movements - but by how much? Dalbergia melanoxylon (grenadilla) offers E=20GPa along the fibres and rho=1310kg/m3, so the tube resonates at nearly the same frequencies as German silver. Its intrinsic losses (tan=0.6%) outperform German silver but probably not sterling silver. The usual thicknesses make the tube about as stiff as with metal. But thick wood improves the oval deformation I described here on Nov 13, 2017 http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/111316-woodwind-materials/?do=findComment&comment=1023070 Dalbergia retusa (cocobolo) brings only E=11GPa for rho=950kg/m3, so it has more resonances than grenadilla, and these are stronger, as tan=0.9% can't compensate the lack of stiffness. Buxus sempervirens (boxwood) has only E=9GPa for rho=930kg/m3 but tan=1.5% is better. It made clarinets before exotic wood became available. Unloaded plastic has bad E=2GPa for rho=1050kg/m3. Expect 3* as many flexural resonances as with grenadilla. Only damping helps, hence the choice of ABS or PP. PMMA cumulates bad damping, as already heard at an oboe. Stiff and damping materials give reed instruments more blowing resistance and make them louder. All is consistent with the usual claims about woodwind materials. Cu-Mn alloys bring high damping, are cheaper than silver but unusual and they resist corrosion less. Worth a try. Reinforced plastics can offer 18GPa for rho=1200kg/m3 with 30% of short graphite fibres. As good as wood, and better in the transverse direction. The difficulty is to damp the vibrations, which graphite fibres don't. Aramide fibres would but they're difficult to machine. Hence my hope with polyketones, or maybe ABS. ========== I'm convinced that some luthiers know much more about theoretical acoustics than university science does. Anyway, I haven't seen the model I propose in academic books nor papers. This explanation has been sought for a century and a half. Now that I know an explanation, I'll surely notice the effect far better. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Materials

The flexural resonances of the body explain decently the material's influence on a woodwind. The air column's oscillating pressure creates a force on the tone hole covers, but their pads are soft and don't transmit the force to the body. This holds above the covers' resonant frequency, which is well within the playing range for a flute. Then the radial force on the tube is unbalanced where the cover doesn't transmit its fraction. The resulting lateral force lets the body vibrate. It has many resonant frequencies within the playing range of a flute, and if the metal resonates strongly like nickel silver does (as opposed to sterling silver), then its movements versus an immobile cover create a volume oscillating in phase quadrature with the pressure - a loss. Notice that the own movements of the covers versus the tube create losses too, better known already, which isn't my point here. This parasitic volume is smaller than the admittance of the air column, but it contributes much to the otherwise small losses of the instrument. Quantitative explanations should come for a Boehm flute. I expect this process to matter for all woodwinds. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Quick Electric Machines

No hard limit. It's a matter of diameter, of an angular speed convenient for the other items on the shaft, and of optimization rather than clear barriers. Magnetic materials can operate at kHz, MHz, even GHz (though less useful at many GHz). But over few kHz, the good materials use to be brittle, which I'd dislike at an aeroplane. One can misuse iron laminations at higher frequencies, but at some point the higher frequency becomes a drawback then, not an advantage. Power electronics can still switch efficiently at 100kHz for instance, but in the MW or GW domain, lower frequencies are better. Then you want to switch must faster than the produced waveform that powers the machine, which puts a strong limit. My waveforms are a new solution to this https://www.scienceforums.net/topic/110665-quasi-sine-generator/?do=findComment&comment=1041409 Electric machines improve with the peripheral speed, which is limited by feasibility (in a dam), centrifugal force, and possibly the speed of sound and aerodynamic losses. Presently, a sleeve of hardened steel circles the fastest rotors. I proposed to wind graphite+matrix filaments instead. 50-100m/s is common in 1GW turbogenerators, 200m/s is reasonable with permanent magnets, while variable reluctance can be much faster. A small centrifuge can rotate much faster than 400Hz, but a D=1.3m turbogenerator rotor at 100m/s only achieves 25Hz.