Everything posted by Enthalpy

-

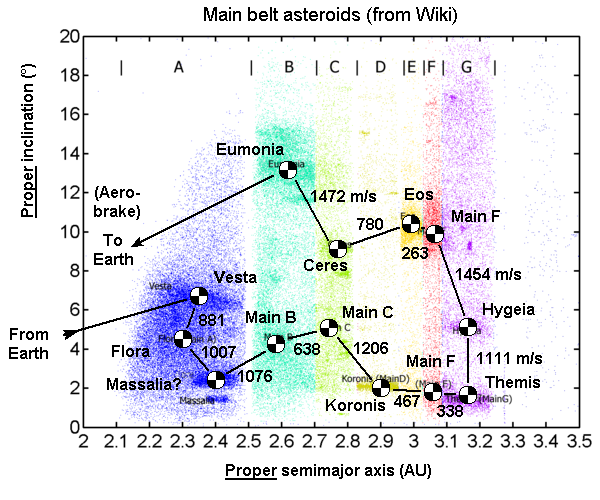

Solar Thermal Rocket

At the main belt asteroids, Dawn observes the surface of Ceres and Vesta, other probes passing by have imaged half a dozen small bodies more, and telescopes give optical spectra from the surface of whole bodies. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asteroid_belt A mission to analyze them in situ and bring samples back would benefit to science, potentially to the extraction or production of propellants for farther trips, and hypothetically to the extraction of precious metals brought back to Earth. A return trip passing by many main belt objects needs a huge delta-V and a decent thrust made possible by the sunheat engine. It begins like the asteroid mining mission here above: an Ariane 5 or Atlas V 551 delivers the oversized 18.5t craft in orbit. Solar, chemical and solar pushes put the probe in transit to the main belt - 10.5t because the first target orbit in the Vesta family is at 2.35AU only but inclined 6.7°. Pushing 4560m/s there, in 132 days with 8 engines, leaves 7.3t at the first asteroid. Venus flybys may improve. The asteroids' actual "osculating" orbital elements look pretty random, but Kiyotsugu Hirayama saw that Jupiter lets them fluctuate. He computed "proper orbital elements" as mean values, and then the asteroids make clearer families supposed to result from shattered bigger bodies. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asteroid_family Sampling a few bodies in each family, plus some outside all families, seems a good plan. I estimate the mission delta-V based on the mean "proper" orbital elements, but the actual "osculating" elements differ much, so among hundreds of family members, a wise and well equipped mission planner would pick more favourable ones. To evaluate individual transfers, which can't await the best date to change the orbit inclination, I combine quadratically the polar component of the speed difference with only half of the ecliptic component and leave the other half untouched. Stopping at intermediate objects is for free, and because I've been pessimistic above, I neglect the orbit fine-tuning and the operations near each object. A well chosen set of target objects would change radically the mission duration and delta-V. The unoptimized sketched tour costs 10 693 m/s from Vesta to Eumonia families, leaving 3.1t there. Landing on bodies up to km size is for free and a spring lets lift off. Ask someone else how to analyze, scoop, dig, bore samples there. A Yag pumped by concentrated sunlight and a hydrogen gun shall perform remote analyses at bigger objects. I already described light samples boxes and sealing apparatus there http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/85103-mission-to-bring-back-moon-samples/?do=findComment&comment=823276 The science instruments can be discarded before heading to Earth, one optional hydrogen tank there too or a bit earlier, the structural truss early if possible. The craft brakes within the asteroid's orbital plane by 4724m/s in two kicks well spread over two revolutions in order to synchronize itself with the Earth and makes a 200m/s fine tune. Other transfers would be faster. If nothing has been discarded, this leaves 2.1t heading to Earth for aerobraking, say over Antarctica. The insulated cooled tanks, the structure and the engines shall weigh 0.9t, equipments 0.3t, experiments 0.3t, leaving 0.6t for the reentry capsule(s); dropping unneeded mass early would increase that. The 600kg comprise 29% structure, 21% heat shield, 13% parachutes, 7% boxes and 30% = 180kg samples from dozens of asteroids all over the main belt. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Electric helicopter

Many companies and groups have flown drones and quadcopters from a fuel cell and hydrogen stored as a compressed gas or a liquid, as you guessed. As one example, Energyor Technologies Inc. from Montreal flew a quadcopter for nearly 4 hours in 2015 - videos available on the Internet. They imagined oilfield operations, powerline inspection... as their first customers. But build a bigger hexacopter (October 05, 2013 here), and this flight duration is fantastic for rescue and search operations. ---------- The explosion hazard with liquid hydrogen isn't as critical as I had believed, at least in air. Arthur D. Little Inc. experimented it in 1960 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7bFJK5kU_UQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RNzjksIImb8 The first video shows from 2min50 to 6min18 spillages of 1 to 5000 gallons ignited late, and in the open air they didn't detonate, but deflagrated instead. Other questions were investigated, for instance the evaporated spillage remains close to the ground over 200m and propagates a flame over 100m. But with liquid oxygen (second video), detonations do occur, said to be less bad than with kerosene.

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

At least two companies want to mine the asteroids for precious metals. While I have no knowledge hence opinion about the wealth available there, I claim that the sunheat engine can bring a heavy load there and back to Earth. Near-Earth-Objects would be more accessible, even to chemical propulsion, but may not be varied enough to offer useful resources, so the goal shall be in the main belt. I take an arbitrary asteroid at 2.8AU from the Sun in the ecliptic plane. As we ignore if water is available near the wanted ore, the script I propose uses no propellant gained there. ----- Escape ----- An Ariane 5 or Atlas V 551 shall put 18 500 kg on a naturally tilted 400km orbit, beginning as described here on Jul 27, 2014. Eight D=4.572m sunheat engines raise the apogee to 60 000 km and detilt the orbit as needed; this takes approximately 1 year and, the long pushes at perigee being 90% efficient, leaves 14 640 kg. Then, an oxygen-hydrogene engine adds 565+1096m/s at perigee to escape Earth and provide 5000m/s asymptotic speed to the remaining 10 190 kg. Escaping with the launcher's upper stage looks seducing but its tanks aren't insulated for one year, so the craft needs an insulated oxygen tank with cryocooler and a chemical engine. A car fuel cell or a lithium battery rotating electric pumps can make a small engine very efficient, but I've taken Isp=4590m/s only. After escape, the chemical engine and the cooled oxygen tank are discarded, leaving 10 000 kg in transit. ----- Transit ----- The sunheat engines add in 8 days 1373m/s near Earth for a Hohmann transfer and 4887m/s in 168 days near the asteroid. A spiral transfer is nearly as good, so even unfavourable inclination changes at mid-course are affordable. 500m/s more account the path corrections. This leaves 5804kg near the asteroid. Here the craft could discard a hydrogen tank and, if not done earlier, the external truss. Not vital for the mass, but it can ease the landing. ----- At the asteroid ----- The sunheat engines operated normally would land and lift the craft from a dense D<600m asteroid only, but the craft can also eject luke-warm hydrogen, and even better, it can have a spring. One small nitrogen spring lifts the craft from an asteroid of several km size. The hydrogen consumption is negligible if any. A first mission ends there, having brought 4.5t of mining equipment that begin operations. What and how, ask someone else. The following missions load 1t of precious metal purified in situ and lift off with 6804kg. ----- Return leg ----- The sunheat engines brake 4887m/s in 134 days near the asteroid. Later, they apply a 500m/s correction. This leaves 4410kg heading to Earth. One or several reentry capsule carry the precious metal and total 2700kg. Their structure makes 29% of the mass, the heat shield 21% for a reentry at 12 877 m/s (slightly more than Apollo), the parachutes 13%, and the cargo 37%. The 1710kg ferry can burn in the atmosphere or change its path. Refilling it seems more complicated than useful. ----- Ferry ----- 10 450 kg hydrogen fit in 155m3, too much for the usual fairings. Instead, a truss at D=5.4m can hold a D=4.8m H=12.5m balloon, plus the oxygen, all engines, the capsules, the equipment, making it somewhat taller than usual - or broader. Made of graphite, the truss weighs 250kg, the tank 260kg, it foam 64kg and the 20-ply superinsulation 108kg, while the aerodynamic shell elements are discarded when exiting the atmosphere. The chemical engine and oxygen tank are accounted elsewhere, so 1710-682=1028kg include the cryocooler, the equipment and undetailed items. Maybe the ton of cargo can increase a bit. The hydrogen tank would leak 60W from 300K to 20K. The cryocooler may need 3kW electricity when the sunheat engines idle. As a cheap source, the 8 concentrators can feed 180kW light on small solar cells. This drops at the asteroid, but the heat leak too. Alternately, an uncooled hydrogen tank may perhaps suffice, if its external skin is colder and its insulation better - to be thought with calm. ----- Economics ----- Chemical engines bring nothing back from the main belt, electric thrusters only gram samples, but the sunheat engine one ton cargo. Gold and other precious metals sell for 40M$, half the launch cost, and the craft costs too. Still imperfect, but that's a first try. Venus flybys improve the masses. The main belt begins at 2.2AU. Falcon 9 Heavy claims to launch for 90M$ 3.4* the payload, which would bring 140M$ gold back. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

What would you change about the new SFN?

Found it, thank you!

-

What would you change about the new SFN?

I didn't find how to insert pre-formatted text, or equivalently for my purposes, obtain a fixed-width font. The equivalent of html <pre> </pre> tag, or to courier new. It would be useful to align lists of numbers, for instance there at the end of the message: http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/76627-solar-thermal-rocket/?do=findComment&comment=1011042 Or is it already available somewhere? Thanks!

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

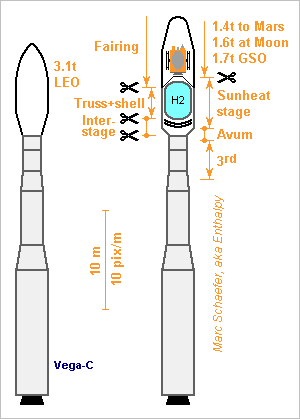

The coming Vega-C would benefit from a sunheat stage: from estimated 3.1t in 400km 5.4° Leo, the sunheat engine would bring 1.7t directly in Gso, 1.6t in 300km Lunar orbit, 1.4t in transfer to Mars. As much as Soyouz from Kourou: game changer. Just 6 sunheat engines, easier to deploy, would spiral to Gso in 26 days plus eclipses - a Gto step would gain 90kg payload but take 130 days, while 2 spiralling sunheat engines gain as much in 78 days plus eclipses. 8 sunheat engines can raise the apogee in approximately 6 months if making less efficient long burns in the very last orbits, and eventually put 1.6t on a 300km Lunar orbit, or 1.4t in transit to Mars where the probe can aerobrake. That's more than Spirit and Opportunity (1063kg) got from the Delta II Heavy: cheaper science! While the launch company could operate the sunheat transfer to Gso, this needs long-term navigation sensors available at the payload, and space probes' operations are longer, so the spacecraft team will more likely operate the sunheat stage. The stage is nearly identical (1274kg LH2, 4 to 8 engines) for these three goals and may be supplied by a third player. 1973kg LH2 would transfer 0.7t directly to Jupiter and 0.8t to a low Martian orbit (figures suggest the tank insulation avoids a cryocooler). Bigger tank bigger for all, or only for them, or scale the payload down. This tank doesn't fit in the Vega-C fairing, hence is a separate stage. An interstage, guided by rolls at separation like for Zenit, gives room to deploy the concentrators. The stage needs a different fairing and trickle hydrogen before the launch. Vega has none up to now, but Ariane 1 had it on the reused ELA-1 launch pad. Here's an estimation of the stage's dry mass, built as described there http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/60359-extruded-rocket-structure/?do=findComment&comment=761740 and followings. 40kg Ballon of steel sheet 92kg 50mm foam for 15min without trickle hydrogen 52kg 20 plies MLI for months in vacuum between uses 4kg Polymer belts holding the tank 70kg Truss of welded AA6005 tubes 96kg Eight engines D=2.8m 30kg Engines' deployment and orientation 50kg Undetailed 0kg Shell already thrown away, interstage too 0kg Equipment bay is in the spacecraft -------- 434kg Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

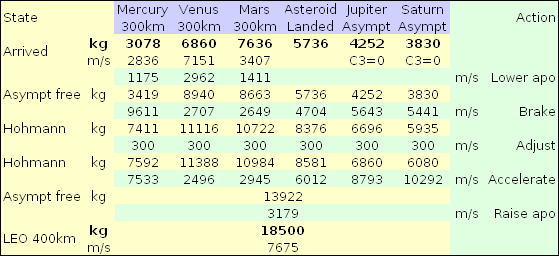

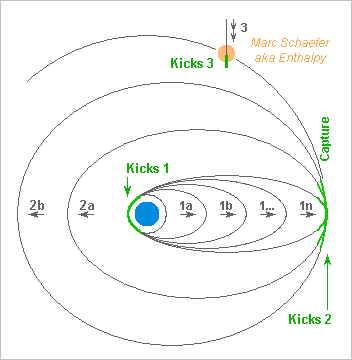

The following script goes from low Earth orbit to remote celestial bodies using only the sunheat engine and eccentric orbits. It's slower but more efficient than spiralling near the celestial bodies. It's slower but more efficient than escaping Earth with only a chemical engine using the Oberth effect, as I suggested there http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/76627-solar-thermal-rocket/?do=findComment&comment=807522 more so because present launchers are badly suboptimum for escape missions. It is less efficient than changing the apoapsis with the sunheat engine and using a chemical engine only for Oberth effect, as I proposed there http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/76627-solar-thermal-rocket/?do=findComment&comment=818683 but it saves the chemical engine ignited months after the launch. The script starts from a tilted 400km Earth orbit with 18500kg, the capacity of an Atlas V 551. Ariane 5 carries a bit more. The probe raises its apogee with many pushes around the perigee, long hence using 90% of the sunheat engine's performance. Symmetric operation at the remote celestial body. I neglect the small Oberth advantage at escape and capture, but don't include other small costs like tilting the orbital plane. Acceleration and deceleration to Hohmann speeds are done at full efficiency. The script is for conventional situations. Mercury's orbit is elliptic and tilted, neglected here. Reasonable planning would make one pass by Venus to gain much mass without wasting time. And a hectare Solar sail is already good at Mercury http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/78265-solar-sails-bits-and-pieces/?do=findComment&comment=763027 Aerobraking is an option at Mars and also Venus. The asteroid is small and at arbitrary 2.6 AU. Capture at Jupiter or Saturn is excellent with the sunheat engine. I don't detail it because missions want too varied orbits. Venus, Venus, Earth (and Jupiter) flybys would gain much. Capture by Uranus and Neptune demands a chemical engine, which can then serve to leave Earth, so they would use the previous script. The chemical engine gives 18% (asteroid) or 24-30% (others) more mass but the present script simplifies the craft. ---------- Erratum to the previous script on Jul 27, 2014 http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/76627-solar-thermal-rocket/?do=findComment&comment=818683 en route to Mercury, the mass in Hohmann transit is 8779kg not 6244kg, and the follow-ups increase by 1.41 too, including the arrived mass: 3835kg not 2719kg. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

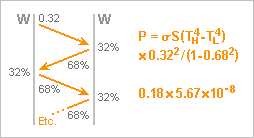

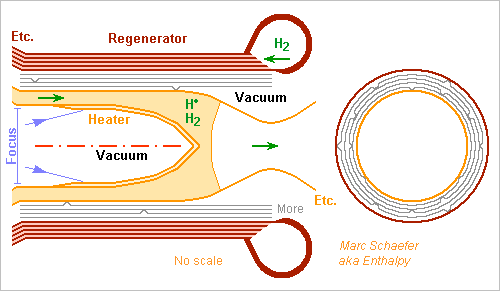

The regenerator's coating was to reflect 98% of the light emitted by the envelope of the chamber described on Jun 23, 2013 http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/76627-solar-thermal-rocket/?do=findComment&comment=753432 but tungsten that sublimes from the envelope would deposit on the regenerator, spoiling its reflectivity. And nobody tells me a word. Fortunately, hot tungsten can make a multilayer insulation. Imagine a D=56mm L=150mm eps=0.32 envelope (for Ariane-class D=4.57m concentrator that catches 22kW at 1AU) at 2800K: it would radiate 29kW, but we prefer 1kW transferred to hydrogen in the regenerator. The 1+16+1 layers need only these temperatures: 2800 2759 2716 2672 2624 2574 2521 2465 2404 2338 2266 2187 2098 1995 1874 1724 1519 1161K where the T<sup>4</sup> decrease uniformly - but the emissivity improves at cold. To separate the sheets, a few stamped bumpers limit the contact area. D=2mm contact and 500µm thickness conduct 8W to D=10mm with 50K drop: as little as D=15mm radiate. 3+3 bumpers should suffice, offset between the layers. Welding at the bumpers seems possible. I don't prefer the usual fabrics because thin wires sublime quickly. 2800K sublime 115µm of the tungsten envelope per month (years-long thrust needs rather 2620K) and this halfs at successive insulation layers. Condensation lets the sheets gain thickness as a mean, so they can be thin, especially the colder ones. From some 2000K down, fewer tantalum sheets with lower emissivity can replace tungsten. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

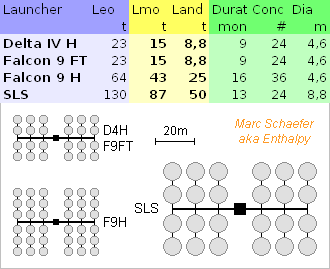

Some second-hand data about ISS' solar panels: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/1053725.stm http://www.nieworld.com/special/hotcold/qtoz/space.htm 1/4 ISS' area cost 600M$ and weighed 17t (without the trusses). It improved meanwhile, hopefully. As opposed, the sunheat engine can transport heavier freight to the Moon, matching the capability of heavy launchers supposed to be cheaper per kg. 23t satellized by Delta IV Heavy or Falcon 9 Full Thrust need 24 D=4.57m engines to reach the Moon in 9 months. 64t by Falcon 9 Heavy need 16 months plus one eclipse season, and 36 engines. A wider fairing would be useful. The Space Launch System foresees a D=10m fairing, so 24 D=8.8m engines need 13 months plus one eclipse season. The engines' arrangement is nothing definitive. The landed mass results from O2 and Pmdpta. Instead, a few RL10 to burn hydrogen are very attractive. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

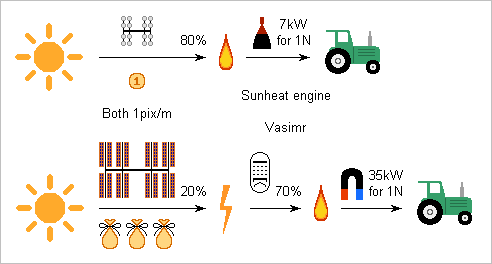

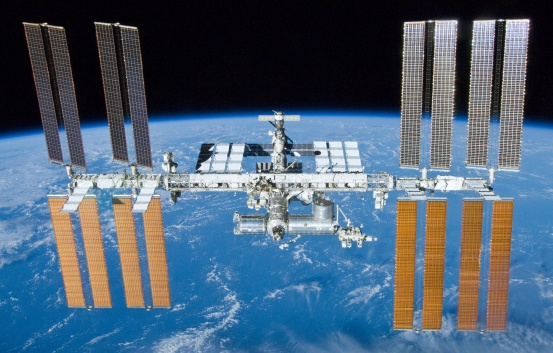

While the sunheat engine converts efficiently sunlight into kinetic energy, the Vasimr obtains electricity first, which is inefficient and costly, and it needs also more power (but less propellant) for the same thrust. Other electric engines tend to be less efficient and strong than the Vasimr. http://www.adastrarocket.com/aarc/VASIMR https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Variable_Specific_Impulse_Magnetoplasma_Rocket The collecting area is a thin mirror for the sunheat engine, but expensive and heavier Solar cells for the Vasimr. 20% light to electricity is a rough figure; better cells cost more per watt. The Vasimr converts well electricity into kinetic energy of the expelled propellant, but for Isp~5000s, it needs 5* more power and 1/4 as much propellant as the sunheat engine with Isp~1267s. The Vasimr can also use less electricity and more propellant for the same thrust, but it first spends ~100eV to ionize the argon, so tuning near Isp~1200s would waste most power. Near Earth, the sunheat engine would commonly use an elliptic transfer to save propellant and the Vasimr a spiral one to limit the collecting area. This reduces the Vasimr's advantage on propellant consumption from 1267s/5000s to 2.4t/5.3t in the previous freight transfer from Leo to low Moon orbit - and the heavy Solar panels reduce the payload. To illustrate the sunheat engine versus the Vasimr: Not for the same thrust, which would be unfair, but for the same time to bring freight from Leo to low Moon orbit, as described here on Aug 13, 2017. The Solar panels are 3/4 as huge as on the International Space Station, and the 16 Sunheat concentrators for 9 months are at the same scale. Here a picture from ISS; the central modules have D=4m. Solar panels have become cheaper than on the ISS, hopefully. For smaller areas, ATK claim their UltraFlex weigh 150W/kg, but on the ISS, the long beams holding the panels weigh tens of tons, excluded for a Moon freighter. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

Esa tries to involve Nasa in a manned base there, and my sunheat engine can transport heavy freight to the Moon. The comparison with other engines holds for other missions. An Atlas V or Ariane 5 shall put 16.0t in Earth orbit, just 400km high, approximately in the Moon's orbital plane. 28.5° inclination is good. ---------- Leo to Lmo with sunheat engines Successive kicks at the 400km perigee raise the apogee to 326Mm. This means 2931m/s, but the long kicks are about 90% efficient. A few kicks raise the perigee to 326Mm and adjust the inclination. 1026m/s, efficient. The Moon passes by. The craft brakes at 300km periselene to be captured and to lower the aposelene from 58Mm to 300km. This means 605m/s at 90% efficiency, plus 50m/s adjustments. The transfer needs 4955m/s performance. ISP=12424m/s let the craft weigh 10.7t on a 300km*300km Lunar orbit. Ten D=4.57m engines make the operation in 15 months, 10 of them for perigee kicks. I neglected the eclipses; launching at the best season void nearly avoid them at perigee. Hydrogen is used fast and often enough to avoid a cryocooler. Taking gas or liquid adjusts the tank pressure. http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/60359-extruded-rocket-structure/page-2#entry761740 ---------- Lmo to lunar surface Deorbiting from 300km costs 63m/s, braking before the surface costs 1880m/s, hovering 3*20s over potential sites and hopping 2*200m cost 160m/s http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/85103-mission-to-bring-back-moon-samples/#entry826166 for a total of 2103m/s. The main and attitude engines can burn at 100bar Pmdpta+O2 expanded in D=1.2m to 1.4kPa for 50kN and ISP=3763m/s=384s. This lands 6.1t on the Moon, including 131kg of Li-polymer batteries that rotate the pumps and are a precious payload too http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/73571-rocket-engine-with-electric-pumps/#entry734835 Liquid oxygen needs probably a cryocooler, while Pmdpta is storable on the Moon. http://www.chemicalforums.com/index.php?topic=56069.msg254340#msg254340 To restart from the Moon after a night, all propellant pairs need some thermal control. These don't freeze. -------- Alternatives to Pmdpta+O2 MMH and N2O4 achieve only ISP=3519m/s=359s with the same pumps and land 5.9t. They are toxic and can freeze. Pressure-feed would be worse. Time for retirement. H2 and O2 give ISP=4423m/s=451s and 99kN in a short RL10A, and attitude control thrusters exist already. It would land 6.6t but needs a hydrogen cooler it this technology restarts from the Moon. Fuel cells to power the pumps would land 0.2t more after a significant development http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/73571-rocket-engine-with-electric-pumps/?do=findComment&comment=737220 -------- Alternatives to the sunheat engines Starting from 7434kg in 28.5° Gto, one RL10A can reach the Moon, orbit there and land, with insulated tanks. It costs 474m/s to 326Mm apogee, 1026m/s to 326Mm perigee, 605m/s to 300km circular Lmo, 2040m/s to descend and land, totalling 4195m/s. Excellent ISP=4423m/s=451s land 2.9t, an incentive for the sunheat engine. Among the electric engines, the Vasimr has good thrust and power efficiency http://www.adastrarocket.com/aarc/VASIMR https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Variable_Specific_Impulse_Magnetoplasma_Rocket The VX-200 shall use 200kW electricity to push 5N by ejecting argon at ISP=49030m/s=5000s. The peak power is huge, so let's have the craft spiral from 400km Leo to circular 326Mm then to 300km Lmo. It costs 7675-1088m/s then 1554-302m/s, totalling 7839m/s. Beginning with 16.0t at Leo, the craft weighs 13.6t at Lmo, seemingly 2.9t better than the sunheat engine. 2364kg argon take 274 days (plus the eclipses) to eject, acceptable. But let's check its solar panels: at the International Space Station, each 34m*12m Solar Array Wing carries 16400 silicon cells of 80mm*80mm to produce 32.8kW during daylight when new https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Integrated_Truss_Structure#Truss_subsystems so 200kW need 6 Solar Array Wings. 500µm silicon make then 50% of 0.7t lost from the payload (ATK's UltraFlex claim 150W/m2 or 1333kg), and the wings occupy over 68m*36m and cost 6/8 as much as on the ISS. Even if accepting some nuclear reactor: 33% conversion into electricity demand to radiate 400kW; at 400K, it takes 2*138m2. The 10 sunheat engines need only 164m2 of sunlight concentrators of thin metal. The sunheat engine needs 7* less watts per newton than the Vasimr, it doesn't waste 4/5 in a conversion to electricity, and its collector area is cheap and light. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

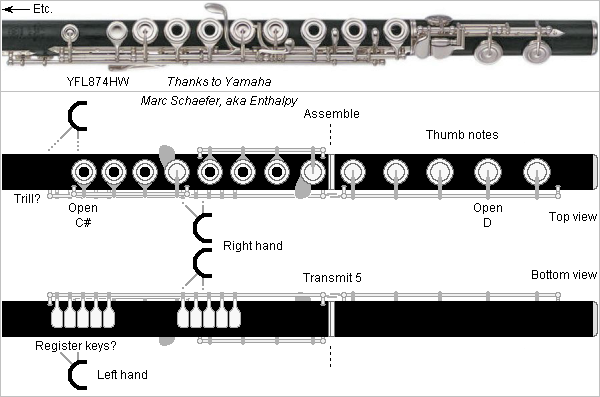

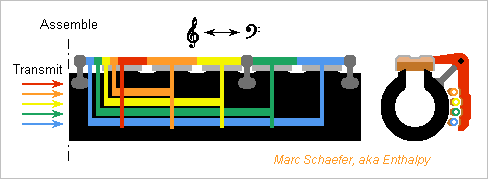

Woodwind Fingerings

This how a flute can look like with the fingerings and keyworks proposed on Jul 02, 2017 11:21 pm. The reference is a YFL874HW, with the strongest low notes of all the flutes I tried. The covers for the eight upper fingers are independent. Drawn with vented covers, in case they bring something. A pair of trill covers can outperform the lowest covers. My fingerings bring the hands nearer to the head, an advantage especially with alto flutes. The musician holds the instrument at the metacarpus to move the thumbs freely; good handles remain to be found. The five lowest covers are open at rest and synchronized as proposed here on Jul 02, 2017 3:37 pm. An alternative would ease the synchronization and the transmission between the joints, with the 2-3 lowest covers open at rest on a shorter footjoint and the others closed at rest on the main joint but often pressed open by the thumbs. As this alternative would have the thumbs release a key when other fingers press some, I prefer the drawn first option, which also enables hypothetical register key(s) opened by the thumbs, with a cover at the headjoint used for instance above the third A. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Fingerings

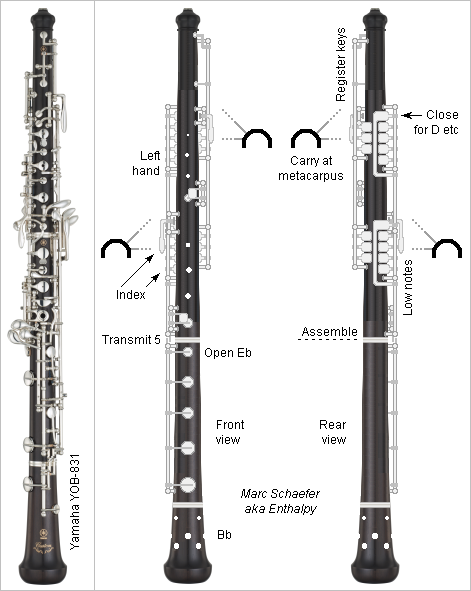

The oboe's visual impression here above gives a sensation of easy prototyping, but developing a woodwind, more so an oboe, is accessible only to excellent professionals. A prototype needs: A tube. That would be the easier part. If you don't have grenadilla dried for 20 years, take a plastic like ABS. Allegedly less good, but it may suffice for a trial. It needs a bore too, by a special-made reamer: obtaining it from a reamer company is cheap but you'll get one single shape, hence the oboe will intonate horribly and fail at the third octave. Alternately, use 3D printing for the tube: flexibility to try shapes, but the material will probably spoil the sound. Keyworks. Much easier: they can be of brass and ugly for a trial. They need pads which can be bought as sets for oboe. The pads must be placed properly at the covers, but all instruments workshops do it, and many musicians too. Bits and pieces from old instruments can serve too, in combination with banal brass rods and tubes. Most instruments workshops can tinker that. Skills, and that a big problem. An oboe needs (non-negotiable) tiny tone holes at bizarre locations, plus chambers at the tone holes, and so on. This needs months of experimentation by the acoustician of an instrument maker. The bore must be adjusted simultaneously. I have only a part of this skill and lack experience. Maybe one or two dozen people have it on this planet, and not at the universities. Software helps but won't replace experience there. So a "quick" experiment with an oboe, where you can plug some tone holes and bore new ones, will only tell if the fingerings are convenient on the two first octaves. It won't tell whether the instrument sounds better on the two first octaves, and even less on the third one, which won't work at all at the beginning. Though, it is my other goal to improve also the sound of the instruments. ---------- A flute would be much easier to experiment. Its tone holes are at the expected positions, its fingerings for the third octave are logical, and modifications to the hole positions act as expected. No big change to the bore is necessary. Many tone holes can stay where they are for a first trial. I expect even the third octave to work (imperfectly) right from the beginning. It could be as "simple" as: take an existing metal flute, braze the C joint to the main joint for the first trial, suppress the thumb C and the small C# holes, add big C and C# holes at the top, simplify the three G and G# holes (or leave these), move the D# hole at the C joint. Make keyworks, mainly from bits of existing flutes. Try the instruments on the three octaves, make an intonation curve, adjust the hole positions accordingly. An amateur can't do that usually, but some flute workshops can. I knew one man (he was 40+ in 1994) in Paris who did it - he let me try the sole and only flute worldwide that intonates properly, including the high G#, because he had moved the tone holes. He, or colleagues as good as him, could make a flute with my fingerings. Hence the quotes in "simple". In contrast, developing an oboe with my fingerings, with a good sound, needs an oboe company, and probably not any company. Simpler trials will only tell if the fingerings are easy on the two first octaves. The bassoon, which needs better fingerings more badly, is even more difficult than the oboe. If it can switch the octave around the C and still reach the high notes, fine... But I don't think so! Presently, it switches the octave at F, a quart higher (hence the many thumb keys), and the Heckel system has even 3 more tone holes, very high on the tube, for high notes. I'm still thinking at it. If I find promising fingerings, they will be badly difficult to implement: design a new instrument with tiny holes and intensive third and fourth octave cross-fingerings. Experience gained at the oboe may help. ---------- Among the oboe-like instruments, a saxophone would be a much easier test vehicle for my fingerings. Its big tone holes are more or less where one expects them, and the influence of their size and position is reasonable. Better: if you keep (at least for the trial) the D to F# keys for the upper register, you can neglect the cross-fingerings. Then, you can just keep the tone holes in a first attempt, make the covers open at rest, and tinker keyworks according to my fingerings. The instrument will intonate badly (more so the short C) and have unequal sound quality, but this version already tells if musicians feel comfortable with the fingerings. A second attempt would correct the sizes and positions of the tone holes, especially the ones that were previously followed by a closed cover. The regularly varying sizes and positions shall provide an even sound quality and ease of emission. More important than easier fingerings on a saxophone, whose throat C-C# are very dissimilar, and low Eb-D-C#-C too. This must be easier at a soprano saxophone, as it fits no assembly between the Eb hole and the too high "D cover" (that emits the E). Synchronizing the thumb covers is also easier at a straight instrument. At this second attempt, the tone holes can already be aligned at the body's upper face to simplify the keyworks. Starting from an existing instrument must be possible but not necessarily easier. The third operation is to make the instrument intonate properly and try to reduce the sound quality mismatch at the octave boundary. Then, one may check how interesting cross-fingerings are for the upper register. More interesting at lower saxophones, as their natural range is wider. My fingerings give full flexibility to their combinations, but a saxophone isn't very good nor logical at cross-fingerings, partly because of the wide bore, and I believe because of the chamber volume in the mouthpiece. The tubax, low sarrusophones and low rothphones would need heavier redesign of the keyworks but benefit more from flexible cross-fingerings at the upper register. The tárogató has smaller tone holes than the saxophone but far bigger than the oboe, and it uses only cross-fingerings at the upper register: it's an intermediate case.

-

Woodwind Fingerings

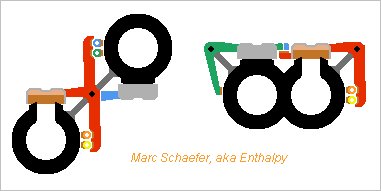

Here's a visual impression of the keyworks applied to an oboe. It looks simpler than the usual keyworks (YOB-831, Yamaha over Wiki), more so as I carefully forget to detail the transmissions and the 3-5 pairs of concentric shafts. The example has two local tone holes per index, an option suggested on Jul 23, 2017: easier drawing not done previously. The musician carries the instrument at the metacarpus to move the thumbs freely. The here undetailed gear shall be snappy to extend or assemble. The small fingers may not need hole covers. I draw 3 register keys for no reason; the same side at both hands looks simpler to build. Notice the D key usable together with the register keys. Synchronizing the lower tone covers was described in Jul 02, 2017's first message. Levers pass the movement from the low thumb shafts to the high cover shafts; as the gear ratio varies among the shafts, a key closing more covers better has a longer stroke. Instead of the oboe's extra lowest cover, I suggest the many holes added by Stowasser to the tárogató's bell - here with two diameters and locations for efficiency. Their adjustment is finer, they permit a shorter (and narrower?) bell part without key transmission. The example has a longer upper joint but a shorter lower one. The holes' positions and diameters must be redefined, since a goal was to suppress to closed holes below the closed-open transition. Now the distribution can vary smoothly for consistent sound quality and response. Double reeds demand narrow tone holes; keep the chambers to dampen the unpleasant highest harmonics; consider several holes per chamber like the bassoon has. One design strategy would decide whether the cross-fingered registers play a full or half note above the flute logic, then design the holes and the bore taper for intonation. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

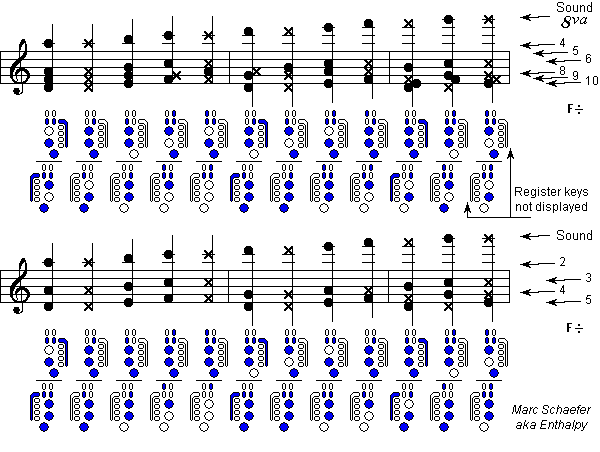

Woodwind Fingerings

Here's an even more correct version of the upper registers fingerings for the oboe family and similar. Hard to draw without mistakes, but never mind, musicians have years to learn and train them. We see that the four highest tone holes (moved by the indexes here) are seldom open simultaneously. The first note needing it is the F three octaves and a quint above the instrument's lowest note, hardly accessible to a soprano, and the (not represented) next one is the C at four octaves and a prime, reachable by few basses and CB. This suggests the next keyworks for the oboe family and similar: saxophone and tubax, tárogató, sarrusophone and rothphone, heckelphone. The four covers shall be closed at rest (eases tightness) and have individual keys for cross-fingerings, plus three keys that open several covers by one finger action for the lower registers. This keeps the alternate action of both fingers on one key at a time, but needs 7 keys for these fingers. Maybe in two rows as on the Boehm clarinet, and indexes shall move a lot. At instruments that reach it, the F requires two indexes, and one shall jump to an other key for some note sequences - or foresee an 8th key to open these two covers. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Fingerings

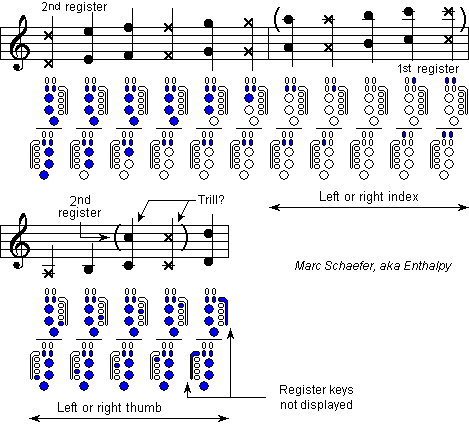

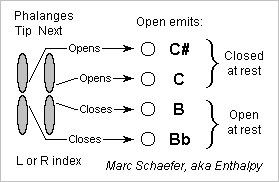

"One key per hole and one finger targeting sometimes several, possibly at different phalanges", as mentioned on Jul 08, 2017, may be better than the six keys moving four platters. When cross-fingerings need both indexes, these can't alternate between the notes; switching betweens the phalanges seems easier than sliding a finger among several keys or key pairs. Applies again to the families of the saxophone and tubax, oboe and heckelphone, sarrusophone and rothphone, tárogató. The flute family keeps its simpler system of Jul 02, 2017, and the clarinet and bassoon families need something else. Here's an example of fingerings for but four octaves, meaningful for contrabasses but plethoric for sopranos. While low instruments with wide tone holes tend to follow this flute logic, the oboe and tárogató intonate the upper registers quite higher; for them, the example merely shows that the system is flexible enough. Below the emitted higher register note, I indicate its sub-harmonics, corresponding to open note holes. Following Obukhov here, one note marked with an x is half a tone higher. Clarinettists happily use the distal and middle phalanges of the left index. For completely independent keys, I feel the height of one must be adjusted to each musician, as is done on some saxophones. The thumbs must press the low D key together with more register keys on the example, hence the elongated shape. The indexes could act separately, each on two tone holes at the top of each hand. The simpler keyworks offer less flexibility at the lower registers. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Bore width of wind instruments

Hello, dear music lovers! I often read that a broader bore gives wind instruments a mellower sound. This comparison holds for the bugle and tuba versus trumpet and trombone, but I claim it should not be extended to woodwinds, especially not to double reed instruments. Make your opinion with two bassoons, both playing very well Saint-Saëns' sonata French system Heckel system More artists have played the sonata, and in every case the Heckel bassoon is prompt to become tinny. The instruments diverged in the 19th century. The French bassoon continued to evolve, but less so than the Heckel system, which was a more radical development from the older instruments. The Heckel system has a broader bore, and its tone holes get wider at the low notes, but it has kept the very long tone holes. The hole system, keyworks and fingerings differ enough to demand re-learning the instrument. The big drawback of the French bassoon: it isn't loud enough! Insufficient in an orchestra. Julien Hardy luckily played with a civilized pianist. And for a solo over a symphonic orchestra: no chance. So it has but disappeared.

-

Hear a tárogató

Original Tárogató music, neither folklore nor lengthy sheet with the superfluous reverberation: http://www.paschart.ch/music/instruments/tarogatos.html the two other instruments could be tenor tarotatok.

-

Woodwind Fingerings

Being narrow contrabasses, both Tubax (which are morphed saxophones, longer and narrower) must have a huge natural range. http://www.eppelsheim.com/en/instruments/tubax-eb/ http://www.eppelsheim.com/en/instruments/tubax-bb/ Their saxophone fingerings hamper exploiting it as they prevent many open-closed combinations that reach the high notes. The fingerings I last proposed (Jul 08, 2017) improve that. The same holds for the low sarrusophones and rothphones. I would keep independent register keys on such instruments, with no automatic works. A wide set of them, operated equivalently by both thumbs when they don't play the five low notes. But for C-D trill, a single thumb must press at once the cover for D and the (lower) second register key. Tone holes not too large make cross fingerings more efficient. Tube bendings should be wide. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Fingerings

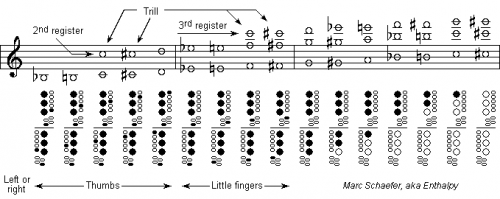

The last fingerings I proposed look excellent for the flute - simple, flexible - and the drawbacks small - high A, middle D and two trills less than perfect. But these fingerings fit the oboe, saxophone and others less well: The middle C on the second register isn't normal on the oboe and is bad on the saxophone; These instrument go usually to low Bb; which justifies my fingerings of Jul 01, 2017 for them. A first improvement is to attribute (approximately) four notes to the indexes rather than the little fingers, because They are stronger, faster and more mobile; They move easily in the opposite direction to the other fingers. This eases cross-fingerings. A second improvement, independently of the involved fingers, is to put the related group of toneholes near to the throat, not to the bell: (Approximately) two covers can then be closed and two open at rest; Moving them takes less force and is more quiet; The keyworks are simpler and easier to adjust; It's easy for the musician and keyworks to open one hole and close a lower one, as needed by high registers cross-fingerings; On small instruments, the hands' location is more comfortable. This example moves four covers from Bb to C# with six keys. Some keys address only cross-fingerings: open C# leave C, or close Bb leave B. Other combinations are possible, including one key per hole and one finger targeting sometimes several, possibly at different phalanxes. Only experiments can tell. ---------- The two lower registers' fingerings with both improvements can become: (click for full size) I won't risk any forecast about cross-fingerings for higher registers on these instruments. Holes can be opened independently from C# down to Eb now - four notes more for big flexibility. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Fingerings

Amazing. I only don't see why it should be called "flute", but to my opinion, synthesized music doesn't need to reproduce existing instruments. By the way, this sound is periodic, as about any one from a synthesizer, so it has no chance to imitate a flute, a sax, a violin... whose sound is inherently non-periodic. The misconception (sound quality = harmonics) dates back to Helmholtz and is carefully propagated to new student generations since then. With a periodic sound, one can more or less imitate a clarinet or an oboe.

-

Woodwind Fingerings

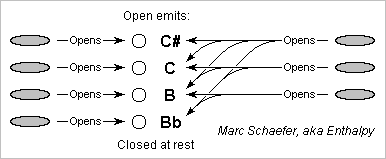

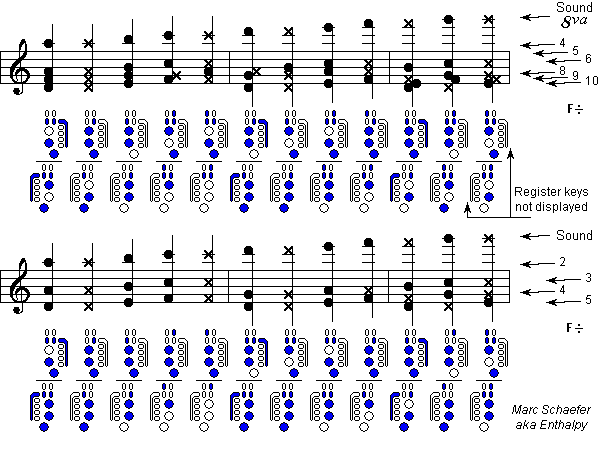

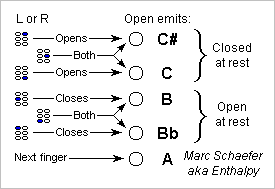

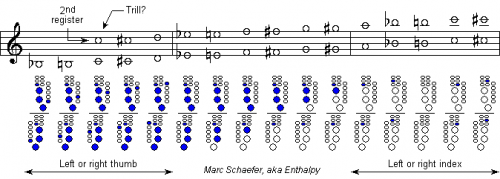

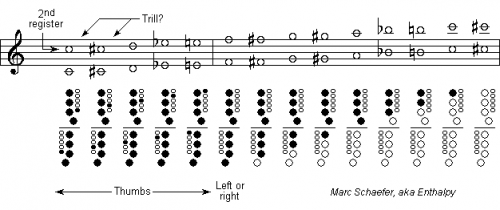

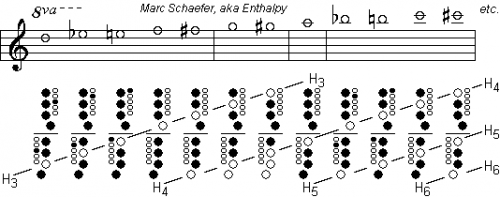

The flute should benefit from my fingerings (hopefully). Since Boehm's excellent improvements, every design detail thrives to minimize the losses: huge tone holes, no register key, at least two consecutive tone holes open at the main closed-open transition... Any departure results in a weak and dull sound. For instance the C# hole, which is located at D and is an oversized register key serving for just three notes, is far too small as a C# tone hole and makes horrible notes. F# are played with the ring finger, making difficult transitions with E. Eb must be opened but for D, whose transitions with any note are difficult. Cross-fingerings make the complete 3rd octave, and the combinations they need exclude many useful variations, for instance F# closing G# as on the saxophone. And as the 3rd G# uses a wrong tone hole ( C) it's badly low - I've played two exceptions only. As a consequence, the flute has cumbersome fingerings, and about any small improvement is excluded. But I hope a big one is possible - tabula rasa. ---------- Here the little fingers act like the six others to provide a half-tone each instead of four together. The thumbs make 5 more notes, as most flutes go to low C, and have no register key. The flutist shall hold the instrument (very precisely as a flute) at his palms with handles like a bassoon; this needs careful design. Click for full size: Fingerings are uniformly easy on the two first octaves. Trills at the lower end of the 2nd octave are questionable, since these notes aren't good on the Boehm flute. Maybe an added low B improves that, or a tiny register key serving for these C C# D only and opened by a thumb key along the three note keys for simultaneous use - or add the usual trill keys near the throat. ---------- Being completely independent, the high 8 note holes give full flexibility to cross-fingerings at the 3rd octave and above. Written one octave lower than it sounds. Click for full size: Simple logic (H3, H4, H5, H6...) applies fully to the Boehm flute and I use it here too. D Eb E F F# (optionally C#) open one hole at the 3rd pressure node and all holes beginning at the 4th. The thumbs note holes are not displayed, only the keys. G G# could also open just the holes at the 3rd and 4th pressure nodes and all holes beginning at the 5th. Not done on the Boehm flute, may ease the pp. G# must intonate perfectly, big progress. A can only open the holes 3rd and 4th+ nodes and should be nearly as good as G on present flutes, not as good as A which opens the 5th hole too. Bb B C should improve as they open the proper 4th 5th 6th+ holes. Not needing the trill keys, they make easier transitions with other notes. C# is the last accessing the 4th node but the first accessing the 8th (or 7th) one. Most present instruments can play an F with uncertain stability and intonation. My fingerings improve that, hopefully. ---------- The development of such a flute should be a reasonable effort, as the holes positions and sizes could nearly be kept and their adjustments are intuitive. The C joint is 3 holes longer, the main joint 3 shorter, the head is kept. The rest is keyworks. Beyond the flute, only the clarinet has logical cross-fingerings, but isn't a candidate for such fingerings. The oboe family and tárogató play the upper register with cross-fingerings, so this design for the flute should benefit them as well. Shift all holes and fingerings one note lower to emit Bb, or add thumb keys, plus register keys. Though, the small tone holes, which are vital to a double reed's sound quality, and distinguish the tárogató from a saxophone, make cross-fingerings unpredictable. So a design would need both to define the best cross-fingerings and let them intonate properly, which takes more time. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Fingerings

The thumbs and little fingers must close many tone hole covers at once, and perfect tightness demands accurately synchronized keyworks. ---------- On the saxophone, the F, E and D covers close the F# accurately, with years-proof adjustments through cork thickness, so a small adaptation shall fit my purpose: The tubes' diameter gives stiffness over a good length, the other subparts are cast and soldered, as usual. Lower covers act directly on higher ones, not as a daisy-chain: stiffer and more accurate. Assembling the instrument's joints can be done naturally at the ends of the little fingers' section and thumbs' section. Key overlaps can transmit the movement between the joints as on the clarinet, and pressing the covers down (blue key on the sketch) when assembling spares the corks. The keys for the right little finger can have a common axis nearly aligned with the covers' one, optionally shared with the keys for the left finger. The keys for the thumbs would rather have an axis at the bottom left or right, transmitting the movement to the lower joint at an instrument's side. It seems logic to have the axis at one side for the little fingers' covers and at the other side for the thumbs' covers. Individual finger keys could have acted on several covers at the transmission between the joints, but I expect mounting inaccuracies to create leaks then. It would also demand to press all covers individually when assembling: less easy with big instruments. ---------- If the instrument's section bearing the little fingers' or thumbs' section makes a U-turn, like the boot does on a bassoon, synchronizing the covers seems easy too: Such keyworks look quiet, simple and affordable, and on some instruments (oboe?) the other holes operated by one finger each can be open, with no cover at all. Could that make cheap instruments? Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Fingerings

This first drawn example addresses woodwinds that cover naturally some 2.5 octaves: oboe family, saxophone, tárogató, sarrusophone and rothphone... https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/T%C3%A1rogat%C3%B3 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarrusophone https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rothphone it doesn't apply as is to the bassoon nor clarinet family. The existing fingerings of the saxophone (the sarrusophone and rothphone have the same) are rather convenient but need complicated mechanics, and the holes closed below the height-defining one make the sound quality and intonation unequal. Additionally, the traditional tárogató has less convenient fingerings and the oboe family requires more complicated mechanics. ---------- So that's my proposal, here with 4 plateaux operated by the little fingers and 5 by the thumbs: (click to enlarge) The musician can use the right or left little finger for any of the four notes, and the right or left thumb for any of the five thumb notes. As on the Boehm clarinet, it lets alternate the right and left hands on successive notes. ---------- The little finger keys close 1, 2, 3 or 4 plateaux at once, but at least the fingers don't have to slide between the keys. Big saxophones may better transfer one plateau to the thumbs. Tightness requires accurate mechanics, to be described later. Trills require only to extend the second and third registers by a full tone. For the medium C-D, one thumb must hold the speaker key and the D key while the other trills the C, so either the speaker and D keys must be close enough, or an additional key acting on both is provided. My proposal has just one tone hole for each note. This reduces some losses, and spreads evenly the extra volume of the closed holes, whose effect is easier to compensate, including at the harmonics. ---------- The drawn third register is theoretical! Early saxophones and sarrusophones had foreseen it that way, using the lower speaker hole with the upper tone holes. For supposedly good reasons, they now have extra tone holes to play the high notes on the second register and make trills too. This can combine with my proposal. The note height of the third register and above follows no simple logic with the narrow tone holes of the oboe, bassoon, tárogató, for which the drawn fingerings are inaccurate. Nearly all use cross-fingerings instead, where an isolated tone hole is open at a pressure node (sometimes at several) well above the main transition between closed and open holes. This spoils the lower modes and reflects better the desired mode. My design's highest six tone holes are independent, which gives full flexibility to cross-fingerings, and all the holes open below the main transition ease the emission. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy ---------- Hi DrP, I'll come back!

-

Woodwind Fingerings

Hi DrP, nice to see you here! The very nature and usefulness of a forum are the contributions that don't go in the expected direction, so "isn't what you were looking for" is absolutely fine. A somewhat similar attempt was at the octo-basse, an oversized bowed string instrument made by Vuillaume. As the musician couldn't reach the top of the strings, he played the notes' height on a keyboard, and a mechanical transmission pressed the strings at the corresponding length. No electricity needed. And believe it or not, the Montreal symphonic orchestra has recently bought such an instrument. https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=octo-basse