Everything posted by Enthalpy

-

Quick Electric Machines

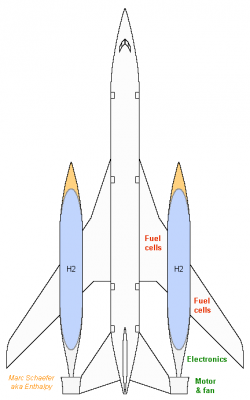

Hydrogen and fuel cells bring less to a supersonic airliner. Fuel cells are too heavy in 2015 for this power, and hydrogen volume creates more drag at high speed. This example is to cruise at Mach 1.3 - but M=0.85 over the continents. Despite the swept wing, I've kept the lift-to-drag ratio L/D=9.3 from Concorde at M=1.3 and added Cd=0.23 drag from two D=4m liquid hydrogen tanks, so L/D=7.6. (Click to see full-sized) The airliner with D=5m body shall weigh 255t with tanks half-full, needing 329kN and 127MW for 387m/s at 17000m. The 85%, 98% and 99% efficient fan, motor (speed makes it easy) and electronics take together 154MWe from the fuel cells. Present car cells weigh 100kg/100kW, so the plane's 154t fuel cells are prohibitive - this is hence prospective. >3 times lighter fuel cells are needed; they improve quickly and have further potential, but through a big effort. The drawn tanks contain 40t together, from which 60% efficient fuel cells permit to fly 7300km at M1.3. Hydrogen needs less mass than kerosene, but the volume wouldn't let carry so much more at high speed. If pyrolyzing to 2*H2, CH4 would cost slightly less than kerosene for the same flight presently; since propane and butane are still torched at oil wells, they too could provide much hydrogen, in addition to propene for plastics and butene for alkylates. Design options and variants: The tanks and cells spread the weight nicely over the wing. The cells can move to the fore and aft to balance the airframe. The tanks need compartments. Between the three hulls is a nice location for stacked wings whose interaction minimizes the wave drag. The F-111's variable-sweep wing would bring low drag at all speeds and improves take-off and landing. In constrast to slower aircraft and helicopters that can fly right now with hydrogen and fuel cells, reduce their noise, gain autonomy and range, operate promptly, save taxiing fuel, supersonic aircraft need more power and must await lighter fuel cells. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Quantum transition software

Hi LoggerTodd, welcome here! If you input all the energy elevels (there are many!) of an element, just a matrix of the differences will tell you the transitions of this element (in the same state, for instance lone atoms). A spreadsheet can do that. It's rather the other way (spectrum to energy levels) that was historically difficult, hi Bohr and the others. One must add some selection rules to filter out the forbidden transitions. This can be done simply from the quantum numbers of the energy levels. Is that more or less your query? Tables of transitions exist as well. Not for every compound, but for the elements certainly. Maybe in the Handbook of Chemistry and Physics.

-

Photocurrent Bias

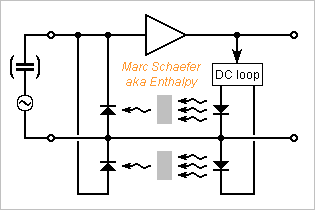

Hello everybody! Some sensors need a huge input impedance: if highly resistive, if capacitive, at low frequencies - reasons vary. Commercial resistors exist up to 22Mohm, uncommonly 100Gohm, and high values integrate badly on a chip; instead, I propose to polarize the amplifier by photocurrents. The loop can provide a feedback at frequencies lower than the signal, or include the signal frequencies, or set a zero when not sensing the signal - or other uses and their combinations. Over a resistor, photodiodes have the advantages of a huge impedance up to some 0.2V, especially if used in the photovoltaic mode (=without external bias) which has zero residual current. This reduces the noise, especially where capacitances and frequencies are small. Over a zero switch, photodiodes advantageously inject no switching charge nor leakage current. Discrete photodiodes exist with a capacitance <<1pF. Within a chip, photodiodes can be made even smaller, adding very little capacitance to a Mos input, and protecting against static charges. In both cases, an optical attenuator can match their sensitivity to the range of light sources. If >0.2V are needed, the diodes can be in series, more can be connected - but two diodes with a bigger bandgap and small leakage would be preferable. I didn't try that one, but it can only work. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Gas Generator Cycle for Rocket Engines - Variants

Hi Jim! Your English works, no worry - and it isn't my mothertongue anyway, so I'm just happy that we share a language. 350 bar is a standard pressure, and you could store pure oxygen, provided you keep much of the CO2 and H2O in the cylinder during exhaust and suck little oxygen at each cycle, to limit the temperature. Similar things are done on torpedoes. Piston engines are not used at full-size rockets because: They're too heavy! For instance the RD-180' turbopump on Atlas has 100MW shaft power (135,000 horse power). It weighs under 1 ton and is as tall as a person. This boat http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CSCL_Globe has a 70MW piston engine, cute picture there http://gcaptain.com/worlds-largest-containership-also-sets-record-for-largest-engine-ever/ that's how turbines and pistons compare... Or just have a look at a compressed car engine: the turbocompressor has about the same power as the rest, yet is tiny. Turbines are simpler and more reliable than piston engines. That was the basic reason for airliners to switch to gas turbines. Existing piston engines are too small for a launcher, so reusing a design is no option. For a much smaller rocket, it's better to put pressure in the propellant tanks, or to use an electric motor plus batteries. Electric motors are much lighter than piston engines and batteries are lighter than a pressure tank for air or oxygen. Then, pumps for propellants also are of centrifugal type because of the mass, and an electric motor fits their rotation speed while a piston motor doesn't.

-

Gas Generator Cycle for Rocket Engines - Variants

A deplorable accident reminds us that the F-16 (and seemingly others, as toxicity was feared after a Rafale accident) uses hydrazine in its emergency power unit. No compressor: the pressure-fed liquid (could be a solid) decomposes without oxygen to produce gas at a temperature bearable by a turbine. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emergency_power_unit#Military_aircraft I proposed here many monopropellants as a gas generator to rotate the pumps of a rocket without the bad hydrazine. A few should hopefully work and would feed the emergency power unit just as well - it's the same task. Upgrades!

-

Expansion Cycke Rocket Engines

The Press reports that a studied variant of Ariane 6 has a reuseable first stage, stronger to fly with 0 or 2 boosters where the Vulcain-pushed stage would take 2 or 4. This reused first stage would burn methane with oxygen. My two cents worth of comments: Cyclopropane is as efficient as methane at equal pressure but denser, so the turbopump achieves more pressure. Strained amines that don't burn at room temperature lose only 4s to cyclopropane and methane. Pmdeta must leave the jacket cleaner than kerosene does, cis-pinane maybe. Both are better available, more efficient, and safe. Cooling the jacket with oxygen isn't done now but it would leave the engine clean for reuse. It permits ethylene that outperforms cyclopropane and methane by 2s, and in an expander cycle, safe fuels. I'd already have proposed reuseable pressure-fed boosters for Ariane 6 if data about mass and dV were public http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/65217-rocket-boosters-sail-back/ with oxygen and Pmdeta, sailing back using the paraglider as a kite.

-

Gas Generator Cycle for Rocket Engines - Variants

On May 01, 2014, I proposed to recompose mainly ethylenediamine in a gas generator (good for a staged combustion as well) with some dissolved ammonia to avoid soot. Ethylenediamine is a bit volatile and corrosive, so I checked if 1,2,3-triamino-propane (a ligand known as Trap) could replace it. It can, but needs 2-3 times more ammonia than ethylenediamine does, so I doubt the triaminopropane mixture improves the vapour. Though, triaminopropane in smaller proportion could serve as an antifreeze in ethylenediamine.

-

Bathyscaphe Float

In contrast to potassium, lithium is said (I didn't try) to react not very brutally with water, and itself and the evolved hydrogen not to ignite usually. This would represent a limited risk in open space. Hard chromium is an other candidate as a liner: big elastic strain, thicker layer easily deposited. Though, because lithium is so soft, I'd prefer an electrodeposited nickel or nickel-cobalt layer, which accepts deformations, over the more brittle chromium and phosporus nickel.

-

Bathyscaphe Float

Weighing 534kg/m3, lithium would make a nice float, with a liner to separate it from the water. This sounds a bit bizarre, but after all we have already metallic lithium in batteries all around us. If the float consists of many lined elements, a failure in water wouldn't propagate to the whole float, and would result in a fire if near the surface, and have little consequences at depth. While being lighter than hexane and syntactic foams, lithium is also stiff - much stiffer than water. From 6000m/s sound velocity, the bulk modulus is 19GPa, so 114MPa water pressure shrinks lithium by 0.6%vol or 0.2% in each dimension. The elements can be spherical, without any void: cold isostatic pressing, radiography. They must receive a perfectly conformal coating, for which metal sputtering or evaporation looks feasible. Over this first coating, the liner can be: Malleable, maybe niobium or tantalum. This would resist a finite but big number of cycles, easily experimented on the ground. Hard, with a yield strength exceeding the 0.2% dimension change. At E=200GPa, both electrodeposited nickel-cobalt and electroless phosphorus nickel have margin. Maybe evaporation or sputtering can also make the desired thickness. I'd have a protection against mechanical aggressions, especially if the liner is malleable. Something like strong polymer fibres woven around the liner. While the performance of a lithium float is second to ceramic balls and pressure-aided graphite tanks, it's better than graphite tanks without pressure and syntactic foam, its resistance to pressure gives more confidence, and I prefer the risk of lithium to the one of a vessel with high permanent gas pressure. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Quick Electric Machines

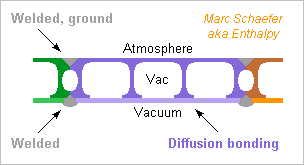

Vacuum or low-pressure vessels are often needed, so the already described extruded profiles, the cast shell elements, the sandwich shell elements (possibly by diffusion bonding) have uses beyond hydrogen storage. Few examples: Some alloys are better cast under vacuum. Vapour condensers and the turbine that uses them. This one may prefer an Al-Mg alloy or titanium.

-

Bathyscaphe Float

Hello everybody! Few vehicles have dived deep in the Ocean, with a crew or not. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bathyscaphe Very few: Piccard's ones to the deepest point of 11km around 1960, a handful much later to 5 or 7km, and recently to 11km Kaiko (lost in a typhon) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kaik%C5%8D Its successor Abismo http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ABISMO Nereus (lost by implosion) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nereus_(underwater_vehicle) The manned Deepsea Challenger http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deepsea_Challenger The float is technically difficult. A hull that resists the 114MPa water pressure is too heavy to float, unless it uses the best materials in an optimized design. http://mseas.mit.edu/publications/Theses/Alex_Vaskov_BS_Thesis_MIT2012.pdf What has worked up to now is: Piccard used a liquid at outer pressure, lighter than water to get buoyancy and lift the heavy crew sphere. Hexane weighs 663kg/m3 without the hull and lifts little, only cryogenic gases would improve. Syntactic foam. Tiny hollow glass spheres load an epoxy to make it lighter. Not very efficient. Nereus uses many hollow spheres of alumina. This ceramic is light, stiff, and strong against compression. The spheres weigh 233kg/m3 hence outperform the previous methods but don't receive universal confidence. A float with titanium or steel shell is no alternative. If breaking at 1.5 times 114MPa, it lifts nothing - it's a candidate for 6km depth only. Maybe silica gel or some zeolite covered with a metal film would resist the pressure, but not lift much. Very hollow solid molecules exist, I don't know their strength. A hull of graphite fibre composite is widely considered, but to break at 1.5 times 114MPa, it would be heavy. ---------- I propose to help a shell with a gas at high pressure. I suggested it there already http://unmoissouslesmers.blog.lemonde.fr/2014/10/07/sous-leau-le-temps-setire/#comment-221 (sorry for ze lãnguage) and meanwhile this idea doesn't seem already common, so here are indications if any necessary. Carbon prepreg is wound on a 0.5mm titanium liner, like tanks for planes and rockets are made. The composite resists 1141Pa compression and 1712MPa tension (other manufacturers give rather 2400MPa), reduced to the half as winding makes it isotropic. Helium at 67MPa helps the shell at depth (114MPa) but must be contained at the surface. According to Soave-Redlich-Kwong, helium's density is 82kg/m3 at +4°C and 67MPa HeliumSoaveRedlichKwong.zip and at +40°C but with the hull streched by 4.6%vol, helium's pressure reaches 71MPa. A 31mm thick sphere for arbitrary D=1m resists 71MPa tension and 114-67MPa compression with 1.5 safety factor (more against buckling) and weighs 142kg. Helium adds 35kg, the liner 6kg. The 524dm3 float weighs 349kg/m3. ---------- Without the gas, the carbon composite float would weigh ~689kg/m3, and with full 114MPa gas pressure ~572kg/m3. Hydrogen is too dangerous, neon leaks less but weighs a bit. Gas pressure would help a shell of 6-2-4-6 titanium also, but the float would still weigh ~634kg/m3, and buckling demand difficult integral stiffeners. Steel is as good but makes the stiffeners more difficult. As a child I wanted to put pressure air in boats so they carry more load. Good idea after all. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Solar fusion, neutrinos and age of solar system

I suggest to compare the masses of neutral atoms of hydrogen and helium, without detailing the reactions in between, since this is the net effect of fusion. The only imprecision is between neutral atoms and plasma, approximately 4*13,6eV versus 24,6+54,4eV: only 24,6eV as compared to MeV, and the kinetic energy of the species, 1keV at 10MK. 4 neutral hydrogen atoms of 1.00795u become 1 helium of 4.0026u, releasing 0.029u of 1.66e-27kg, that's 4.36e-12J per helium atom. Agreed. 3.9e26W need more than (because neutrinos evacuate a part) 1.5e14mol/s helium creation. That's 1.9e28kg/Gyr (billion years). All from Wiki, the core weighing 34% of our Sun's 2.0e30kg being composed of 60% He instead of initial 27.4% has created 2.2e29kg of helium. This would have needed 12Gyr, not 4.6Gyr, agreed as well. ---------- Explanation attempts: Neutrinos evacuate a significant portion of the fusion energy? 60% He is a proportion at the center, not a mean value over the core? The 60% and 27% at Wiki are wrong or undetailed? Nobody measured them. I suppose their difference results from computations like yours, just more differentiated over the depth.

-

Quick Electric Machines

For the vacuum vessel of a hydrogen tank, cast shell elements make naturally a single wall. I prefer sandwich double-walled shell elements, as they resist shocks and deformations far better and offer redundant airtightness. Diffusion bonding permits it; not as cheap as casting, but aeroplanes afford it. Among other providers, a doc with nice examples, sandwiches on page 9 and 10: http://www.formtech.de/download/formtech-short-presentation.pdf and here is how the vacuum vessel may look like: The external skin with stiffeners in several direction, for instance as an isogrid, is cast or rather machined. It can provide the smoothly curved outside aerodynamic shape, while its inner face is machined flat for bonding. The inner skin is a sheet here, though ribs are possible. Diffusion bonding makes a sandwich shell element of both, with manageable size and shape. Then the elements are assembled by Tig, Mig or other welding to make a shell. Milled keys bring accurate positions when welding. Alternately, two thin skins and a (bidirectionally?) corrugated spacer could be superplastically formed before diffusion bonding, if the shells are accurate enough for diffusion. Seemingly, magnesium alloys still don't resist deep bumps. This would leave aluminium (AA5083) and titanium (little alloyed). Cylindrical tanks at rockets can keep my cheaper extruded profiles. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

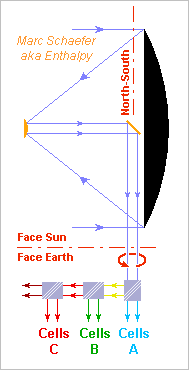

Solar Thermal Rocket

It goes without saying, but maybe better if I say it: concentrated sunlight, split over wavelength bands, has uses not only at Europa. Here electricity production for a geosynchronous satellite: As usual, the satellite's body revolve once a day around the North-South axis to face the Earth, and at its North and South faces, some parts revolve once a year to face the Sun - but here the solar cells can turn with the body. It needs no slipring to transmit the electricity, only a Nasmyth path or similar. Solar cells of varied bandgap can be separated. No difficult new technology, and we can have more different materials. That's much cheaper and efficient. They get their best band through filters. The smaller cell area saves costly semiconductor and work. Concentrated light improves the efficiency further. Heat stays bearable thanks to the good conversion. Fluid cooling is an option. The unconverted light, typically mid-infrared, may power a turbine, or be dumped. The concentrators should be lighter than solar panels of same area, and more so of same power. At 50% efficiency, two D=4.57m concentrators (to fit flat in the fairing) provide 22kW electricity. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Expansion Cycke Rocket Engines

If an engine flows the oxygen instead of the fuel in the jacket to cool the engine wall, for instance if this oxygen rotates the turbine, then the engine can burn ethylene or other fuels unsuited for high temperature. Ethylene is flammable (detonation speed between methane and acetylene) but it brings performance second to cubane only. Here a comparison at the pressures estimated on 30 March, 2014 for a first and a second stage. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Quick Electric Machines

To prototype a vacuum-insulated hydrogen tank as described here on 14 April 2013, one doesn't have to pay the special aluminium profile right from the beginning. Existing aluminium profile is heavier but demonstrates the balloon in an evacuated shell. One example of existing profile, among many from varied suppliers: http://www.bso-gmbh.de/pdf/produkte/alu-profil-nut-8-40x160-4n-leicht.pdf its flat face is easy to weld and 160mm width limits the weld work. ---------- The production shell, sphere-like or more ellipsoidal, can also consist of cast elements, for instance two shell parts with seals and bolts, or 20 triangles welded as an icosahedron, possibly subdivided in smaller triangles, and the many variants http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Icosahedron http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pentakis_dodecahedron http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Truncated_icosahedron cast elements commonly have integral stiffeners. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

A mission to Jupiter's moon Europa, where wild scenarios put a water ocean below the ice crust http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Europa_(moon) benefits from the improved role sharing among the solar and chemical engines, but weaker sunlight there needs time. The already described improved Earth departure sends 7932kg to Jupiter - though I'd have nothing against Venus, Venus and Earth flybys. The probe arrives with asymptotic 5643m/s. The chemical engine brakes by 803+618m/s at 670.9Mm from Jupiter's center - Europa's orbit radius - where the escape speed is 19431m/s. This leaves 5810kg with 10000Mm apoapsis nearly in Europa's orbital plane. The solar engines lower the apoapsis from 5073m/s to 541m/s over Europa's (approximately) circular orbit. Eighteen D=4.572m concentrators push for 3 days around the periapsis so the process takes around 3 years; make science meanwhile. The long push is 80% efficient, so 3683kg head to Europa. Gravitational assistance by Jupiter's four big moons should have brought observations and saved time and mass, but isn't easily accessible to hand computation. The chemical engine brakes by 73+144m/s at 100km over Europa's surface for capture, or 1661km from the center, where the escape speed is 1963m/s. This puts the apoapsis at 10Mm, below the Lagrangian distance, with the preferred orbit inclination, leaving 3512kg. The solar engines circularize the orbit. They provide 431m/s in three months, leaving 3392kg at 100km over Europa, better than 899kg previously http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/76627-solar-thermal-rocket/page-2#entry769456 This includes all the propulsion (about 800kg). The mass can comprise an orbiter, a lander and a diver. ---------- The concentrators have uses beyond propulsion, at Europa and elsewhere, not only as a radiocomm antenna or to warm the spacecraft. Each concentrator catches 827W, or together 15kW. Filters can direct the best frequency band to each use; consider my evanescent wave filter http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/74445-evanescent-wave-optical-filter/ Concentrated filtered light can pump a laser for data transmission and an other to analyze the surface of a celestial body (besides a hydrogen gun). Solar cells get efficient with strong light that doesn't heat them unnecessarily; varied semiconductors would get each the best frequency band. 40% conversion from small cells would already provide 6kW electricity, nice for a radar and for radiocomms. A turbine would deliver more http://saposjoint.net/Forum/viewtopic.php?f=66&t=2051 ---------- More moons deserve their own space probe, like Saturn's Enceladus. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enceladus_(moon) Weaker sunlight there would make the circularization really long, but some answers exist. The concentrators can make electricity over the whole orbit, stored in a big battery, used at periapsis in the solar engines in a hydrogen resistojet mode. Not very good at Jupiter, but interesting at Saturn. The solar engines can trade efficiency for strength. More concentrators, or even (gasp) a lighter probe. Moon flybys are probably the key to success. The solar engines bring the fine orbit correction and the capacity to adjust the periapsis and the inclination. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

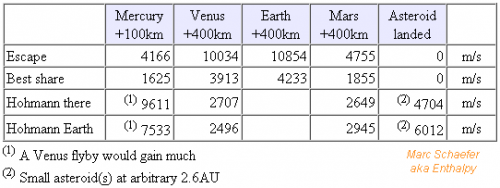

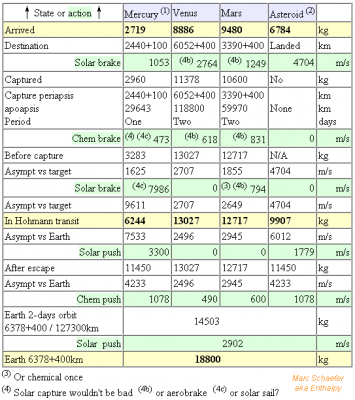

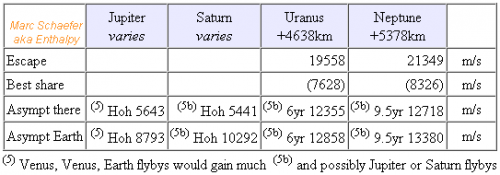

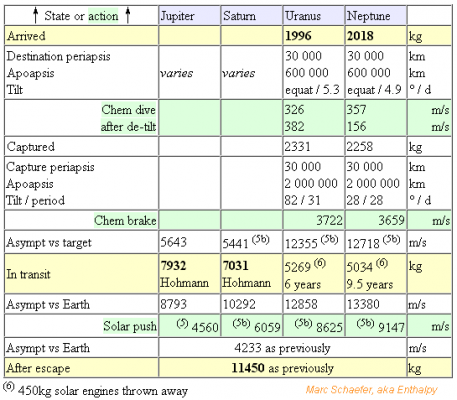

I suggested there how to share the job among a chemical engine that lets a craft escape a planet and solar ones that accelerates it further http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/76627-solar-thermal-rocket/page-2#entry807522 This improves further if the efficient solar engines first raise the apoapsis and the strong chemical engine uses the Oberth effect to escape only - or when arriving at a planet, capture chemically to an eccentric orbit, then circularize by the solar engines. This is an optimum without inert masses, for this more general elliptic orbit: At Earth for instance: an Atlas V 505, an H-IIB or an Ariane 5 can put 18.8t on a 400km orbit (Ariane 5 Me can more... Wider fairing please!). 15 D=4.572m solar engines bring 14503kg to a 2-day orbit with 127300km apogee; this takes 9 months, good for a space probe. An RL-10 kicks 11450kg to asymptotic 4233m/s - or a lighter and more efficient 15kN engine possibly with electric pumps, more careful with the payload, usable at the destination as well. For 2902m/s performance to the elliptic orbit, the solar engines (at 90% isp because of long pushes) bring 1.46* more mass than an RL-10; the advantage increases because the inert mass of a two-stage launcher penalizes an escape mission; and the combined scheme also saves mass at the destination. ---------- At telluric bodies, probes shall usually land or go to low orbit, and sunlight suffices for the engines. In some cases, the chemical kick gives the whole transfer speed. We can send these masses by the improved scheme - now we're getting somewhere. ---------- At Jupiter and Saturn, the final orbit depends on the mission, which must give time to the solar engines. I decribed there a mission to all of Jupiter's equatorial moons http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/76627-solar-thermal-rocket/#entry756421 instead of multiplying all masses by 0.78 following the wrong estimation of the launcher's capability, 7932kg in transfer permit to multiply them by 2.05, so the mission ends at Io with 800kg instead of 304kg. The mission to all of Saturn's equatorial moons, launched by an Atlas V 505 instead of Delta Heavy, http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/76627-solar-thermal-rocket/page-2#entry773439 ends at the A ring with 980kg instead of 689kg. The transfers need such speeds if no flyby helps - optimum to Jupiter and Saturn, accelerated to Uranus and Neptune: The improved scheme sends these masses - in transit for Jupiter and Saturn because the missions vary too much from there on: If a mission needs short pushes there, a hydrogen resistojet and a battery may perform better than direct heating by sunlight. ---------- At Uranus and Neptune, the solar engines would take too long. Chemical engines impose then eccentric orbits. The masses in the table are for twin missions in direct transfers, more accelerated to Uranus, similar to http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/76627-solar-thermal-rocket/page-2#entry757109 http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/76627-solar-thermal-rocket/page-2#entry757109 (multiply all masses there by 0.78: then 600kg in orbit, the new scheme improves to 2000kg) The probe arrives at the point that puts its apside line in the planet's equatorial plane and brakes near the planet. This may put the periapsis in daylight or not. In a first phase, the probe observes the planet from there and looks for new moons. Then the inclination and the apoapsis are reduced in small steps to overfly the irregular non-equatorial moons as possible. When in equatorial orbit, the probe observes the lower moons. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

The continuous faint push of the solar thermal engine makes bad use of the Oberth effect http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oberth_effect Pushing near a planet is much more efficient, so that a strong short kick (possibly at slower exhaust speed) can be advantageous. The solar thermal engine can be operated with a higher propellant throughput for that, accepting less hydrogen dissociation and a lower temperature. It brings a modest advantage. An other option, combinable with the previous one, is to release some heat not obtained in real time from sunlight. For instance molybdenum absorbs 375kJ/kg to melt at 2896K, niobium 288kJ/kg at 2750K, or hafnium... Ceramics or salts may bring more options. How tungsten resists these is very unclear to me. As much heat as 1000s from a D=4.57m concentrator takes 60kg molybdenum near Earth, but just 2.2kg near Jupiter, where the usefulness is clearer. Or add heat from electric current, as in a resistojet. A safe Li-polymer battery store 475kJ/kg, other chemistries more - and better, spacecraft have already a battery. Electricity from sunlight is less efficient, so the continuous push better results from sunlight-to-heat, but lightweight and shared storage is attractive for kicks, especially near Jupiter or Saturn. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

When pumping lasers with sunlight, say at a Europa mission, my filter might also direct to the lasing ledium only the useful wavelengths, to limit heating; it must be inserted where light is parallel. A good 200mm mirror would concentrate light to a 100mm spot from 20km altitude - if only the pulsed laser produced a perfect beam. 150W mean optical power evaporate Europa's surface thanks to the short pulses. If analyzing the shallow surface isn't enough, one could build a hydrogen gun on the space probe, to shoot dense bullets like 1g at 3km/s. These will penetrate deeper in ice, and the probe can shoot 10,000 of them of varied composition to map the moon. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

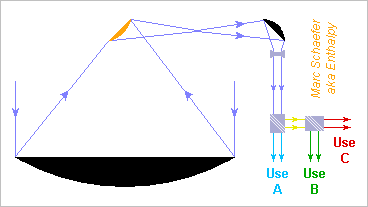

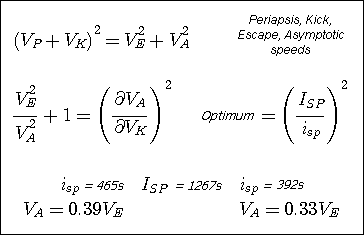

The sunlight concentrators can fulfill more purposes at Europa or elsewhere: As the reflector of a high-gain datacomm antenna. To concentrate sunlight on an electricity generator: http://saposjoint.net/Forum/viewtopic.php?f=66&t=2051 To pump with sunlight a laser, maybe Cr:Nd:YAG. The laser beam might evaporate points of Europa's surface for remote analysis. To pump a laser that transmits data. Consider my filter at the receiver at Earth http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/74445-evanescent-wave-optical-filter/ Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy ==================================================================================== Here's how a chemical engine and the Solar thermal one can share the performance to escape a planetary orbit and achieve an asymptotic speed, with more details than http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/76627-solar-thermal-rocket/#entry754921 A chemical engine can provide a brief kick near a planet which brings much asymptotic speed according to Oberth http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oberth_effect the optimum share is when a relative variation of the begin-to-end mass provides the same speed variation from both engines, including the multiplying factor by Oberth effect. isp=465s for the hydrogen+oxygen RL-10B and heirs, isp=392s for a kerosene+oxygen engine for GTO and escape missions http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/73571-rocket-engine-with-electric-pumps/page-2#entry772828 give an optimum share at 4298m/s (18.3km2/s2) and 3530m/s above Earth's gravity, 1934m/s and 1589m/s above Mars', but: This neglects all inert masses. Two-stage launchers prefer less. This optimum is very broad. 1934+500m/s from Mars loses 0.4% mass overall, 1934+1000m/s 1.7% - room for other constraints or preferences. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

If someone can propose a film as the concentrator, I have absolutely nothing against, sure! Sunlight must be concentrated from a D=4.57m reflector to a focus like d=20mm. While heating does not need an optical quality reflector, it does need a resulting Sun disk nearly the minimum size - if not, the too big hydrogen heater would lose more power through its radiation. I couldn't think of a film setup accurate enough, hence the ultra-thin nickel with stiffeners, as for dish antennas. Deployable film reflectors exist for radio dish antennas, but their wavelength is less demanding. I also like that 4.57m concentrators (or 10m launched by the SLS) allow to test individual engines on Earth in existing vacuum chambers. The heater has about the same 2800K as the filament of a light bulb and radiates almost as effectively... It loses only a fraction of the incoming light power because the Sun is even hotter - but for this comparison to hold, the thermal design must be optimized. That's the aim of my reflective-coated regenerator insulated by vacuum and of my ruminator. As well, optimum operation at Jupiter makes an imperfect heater at Earth, for instance. Either have two specialized heaters, or optimize for the more demanding location, and cut-out the excess sunlight. For Jovian missions, I found the acceleration near Earth quick enough. ---------- A nuclear thermal engine heats and expels hydrogen just like my Solar thermal engine does. The Solar has born advantages to achieve a higher Isp: - It can use just tungsten because no neutronic properties are required. Hotter hydrogen is faster. - At 2800K and only 30mbar, 23% of the injected H2 split into H, absorbing much more heat from a limited temperature. During the expansion, a good fraction of this heat converts to kinetic energy. This was not considered in ESA's design. A reactor would also try to push strongly, and the corresponding chamber pressure prevents hydrogen dissociation. The pressure is constrained by the expansion possibility. In my present design, the mean free path at the exhaust is a few time smaller than the nozzle diameter, so hydrogen behaves like a gas. Less expansion would waste heat not converted to kinetic energy, while more chamber pressure would reduce the dissociation and the isp. I had failed this estimation previously (2010) when I got isp~2200s. A "boosted" operation mode, where more hydrogen gets heated by as much sunlight, increases much the thrust and wastes little isp. It seems useful during certain operations, but at least for the trips around all equatorial Jupiter or Saturn moons, I found no advantage to it. For a capture by Mars or Mercury maybe, since one m/s is worth more near to the planet than far away. I too believe that my engine is rather easy to develop, but as an old engineer, I know well enough that a convincing system design is just the requisite before running into the worries of development.

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

Thanks for your interest! The thrust can be fully oriented independently of Sun's direction by using secondary mirrors, which will probably be present for optical reasons anyway. I suggested a setup there http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/76627-solar-thermal-rocket/#entry752817 but it's merely to suggest that vectoring is possible and rather easy. An optics designer would improve that. I have of course nothing against fibres! Just that last time I threw thoughts at them, what is possible and what isn't were unobvious. I suppose they won't replace the concentrator. As well, the vast collecting area is a design constraint and I wouldn't like to waste even 30% of it, a usual filling factor for fibre bunches. - It's easier at Mercury, sure... - The very efficient use of Solar power converted to kinetic energy is a huge advantage of the Solar thermal engine. Ionic engines for instance would outperform the ejection speed and thus save gas mass, but 30% light to electricity and little converted to kinetic energy makes their Solar panels really impractical for a significant thrust. A nuclear reactor making electricity would require a bigger radiator than the Sunlight concentrators here, while a reactor heating hydrogen wouldn't reach the 2800K for hydrogen dissociation that enable the 1267s isp. In the manned Mars mission script, I need thrust like 100N, and the concentrator area is still feasible (...not small) for the Solar thermal engine. My design for the heater doesn't need transparent materials. It's just tungsten that absorbs light at the vacuum side and heats hydrogen at the other (sure, light at limited incidence and gas at fins) http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/76627-solar-thermal-rocket/#entry753432 "Focus" there designates an immaterial location, the entrance of a hole full of vacuum. Tungsten would be exotic in a car or a PC. For a launcher or satellite, tungsten and its machining are less exotic than niobium alloys for instance. ESA had tried to design such an engine, but had a window and an exchanger made of a rotating bed of ceramic pellets. These were serious feasibility worries and performance limits (isp=800s) at their design. By removing these difficulties, my design looks feasible, and even rather easy. I believe it can become a big thing in space transport, not just a Mercury, Mars or Europa, but also for the geosynchronous orbit. The ruminator and some regenerator details are nice features. As usual, I didn't check if some Sapiens had invented them before. What I'm less pleased with are the concentrators. Made of electrolytic nickel (plus coatings) like satellite dish antennas, they should weigh like 1kg/m2: less would be useful. Though, I wouldn't like to increase them beyond the fairing's diameter. D=4.57m is easy to store and deploy even in big numbers, and the engines can be tested on Earth.

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

As Nasa calls for bids for a mission to Europa, Jupiter's moon supposed to have an ocean of liquid water, I should like to remember the script I proposed in post #25 http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/76627-solar-thermal-rocket/page-2#entry769456 based on the Solar thermal engine whose current description begins with the present thread http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/76627-solar-thermal-rocket/ The existing script is absolutely straightforward and quick, directly from Earth to capture by Jupiter then Europa - something enabled by the isp=1267s from the Solar thermal engine. Though, gravity assist would bring a probe bigger than 900kg to Europa: slingshot at Venus, possibly Earth and Ganymede. I won't explore this scenario soon.

-

Gas Generator Cycle for Rocket Engines - Variants

In gas generators that recompose a liquid, added ethylenediamine and ammonia have drawbacks (toxic vapours, viscosity, melting point) hard to guess on the paper. A more seducing option is to combine the dinitramide with a cation heavier than ammonium. Methyl-, trimethyl- and dimethyl-ammonium dinitramide improve the performance and keep a reasonable pH. Dissolved in water for 700°C or 1100°C, they expand to 1550 and 1850m/s, while from 700°C, added ethanol must thin them, and from 1100°C, gains 100m/s if the mix isn't too thick nor flammable. Guanidinium isn't so good, but di- or tri-aminoguanidinium nitrate replacing 10% dimethylammonium dinitramide avoids alcohols and keeps 1900m/s from 1100°C. Tri- or di-aminoguanidinium dinitramide must be more soluble and efficient, if practical. These aqueous gas generators are second to toxic hydrazine but outperform the explosive hydrogen peroxide by far. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy