Everything posted by Enthalpy

-

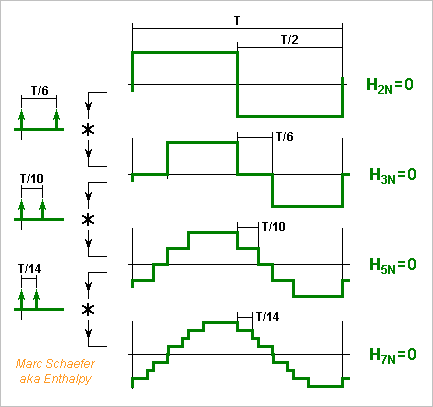

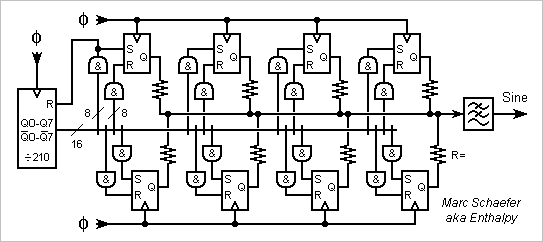

Quasi Sine Generator

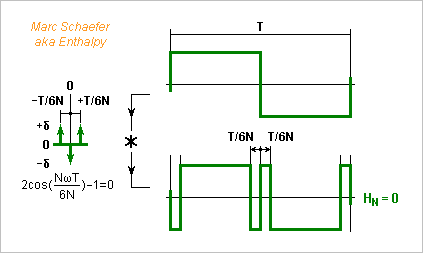

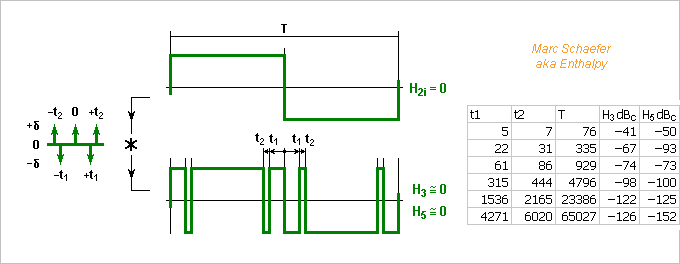

The previous method uses intermediate output voltages to suppress some harmonics. Alternately, the waveform can have more transitions between just two output voltages. This needs only one accurate output and no matched resistors, but reinforces other harmonics and has some limitations. I suppose much of that exists already. ========== To suppress one harmonic, three transitions per half-period suffice. Understanding it as a convolution with a three-Dirac signal spares some integrals and helps thinking further. Convolving multiplies the spectra. With the Diracs T/6N apart, the Nth harmonic cosine in 0.5 there, so its sum over the three positions (the Fourier integral) is zero. The sine is zero by symmetry, so is the power of the harmonic in the convolving signal, and in the output signal too. The transitions are placed accurately by a counter, for instance by 18 to suppress the 3rd harmonic, and the circuit fits nicely in a PAL for instance - with a separate CMOS flipflop for the output, fast to propagate the rising and falling edges with nealy the same delay, and having its own clean power supplies. With a simpler analog filter, it suffices already to measure the second and third harmonic distortion of an audio amplifier, detect the nonlinear antitheft magnetic filaments in goods at a shop, and so on. ========== Can we convolve several times by signals that suppress different harmonics? For the maths, we can combine the convolving signals first. Suppressing one harmonic more takes 3* as many transitions. An output signal of two values needs alternate +Diracs and -Diracs at the combined convolving signal, which happens if the suppressed harmonics' ranks differ by more than 2, annoyingly. For instance the ranks 3 and 5 need more output values hence summing resistors. Could the starting signal be unsymmetrical, like positive for T/3 and negative for 2T/3, to contain no 3rd harmonic? This helps little. One 3-Dirac convolution could then suppress the 2nd harmonic but not the 4th: if meant against rank N, it suppresses also the ranks 5*N, 7*N, 11*N, 13*N... and ranks 2 and 4 are too close for two 3-Dirac convolutions. Can 3-Dirac convolutions combine with the previous multi-level signal? Yes... Think with calm at what rank to suppress by which method so no new output level is needed. Combined solutions use to mitigate the advantages but cumulate the drawbacks. ========== Better, we can convolve the square by a signal with more alternated Diracs, putting more transitions at the output signal to cancel more harmonics. I take here the ranks 3 and 5 as an example (as the initial square already squeezes the ranks 2, 4, 6...) and extrapolate the observations to other ranks or more ranks. The seemingly harmless equation for the angular positions a1 and a2 of the -Diracs and +Diracs at the convolving signal are: 1-2cos(3a1)+2cos(3a2)=0 for H3=0 1-2cos(5a1)+2cos(5a2)=0 for H5=0 I found no analytic solution quickly. The deduced 5th grade equation with few nonzero coefficients may exceptionally accept analytic solutions, but these wouldn't help design an electronic circuit. Instead, I solved numerically a1~0.0656804005273 and a2~0.0925768876666 turns (of one fundamental period) with the joined spreadsheet. Programming, or Maple, or supposedly Mathcad, Mathematica and others would do it too. Squeeze35.zip (unzip, open with Gnumeric, Excel 97...) These parts of a period are not fractions, at least up to 66 000. Fractions can approximate them, and I picked some favourable ones from the same spreadsheet to put on the previous Png. The best denominators (clock pulses per period of output signal) against one harmonic are bad against the other, but I believe circuitry that places the transitions accurately needs one common counter, so I chose denominators decent against both harmonics. Such denominators are big: 4796 to exceed the signal purity of a Digital-to-Analog Converter. 23386 is manageable since the output signal is limited by the propagation time mismatch roughly to the audio band: clock around 23MHz for 1kHz output, and unusual but feasible 460MHz for 20kHz; the signal purity resulting from this approximation only, -122dBc before filtering, is excellent. The circuit to squeeze two more harmonics than the square signal does is simple, notably for programmable logic. The 65027 denominator needs a 16-bits counter with complementary outputs of which the And gates pick 16-bits configurations. Squeezing more harmonics, with more transitions per output period, would take more And gates. Denominators are supposedly less efficient or much bigger. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Fingerings

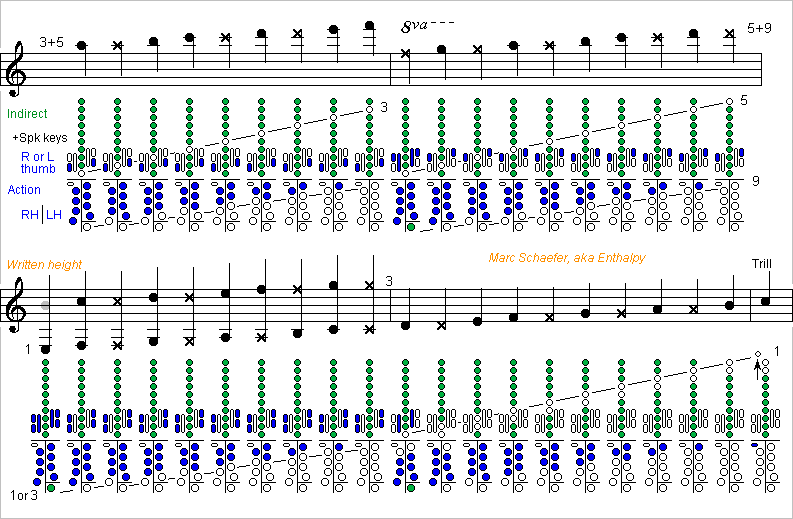

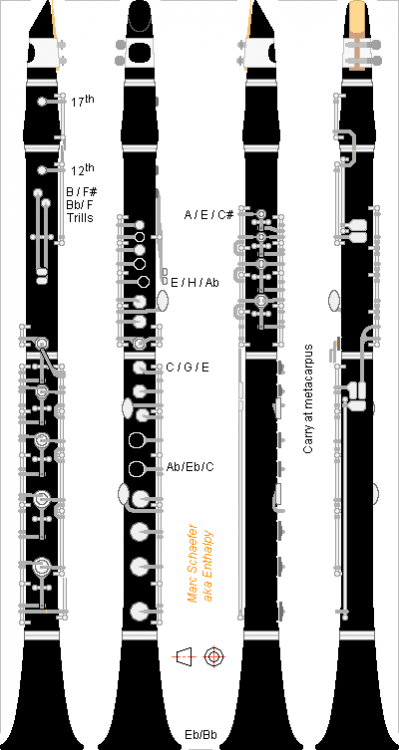

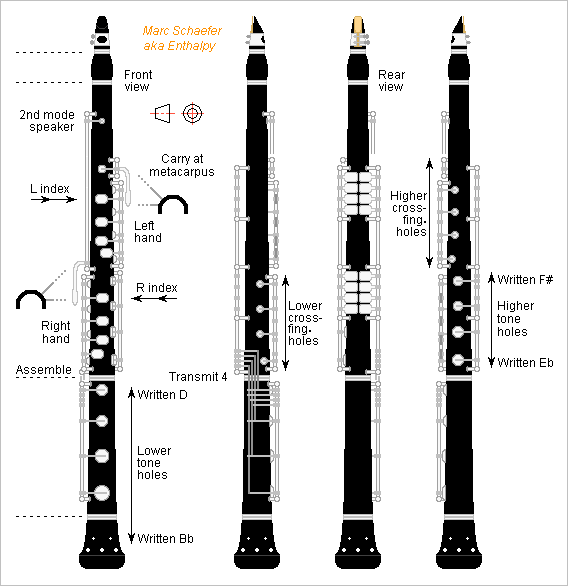

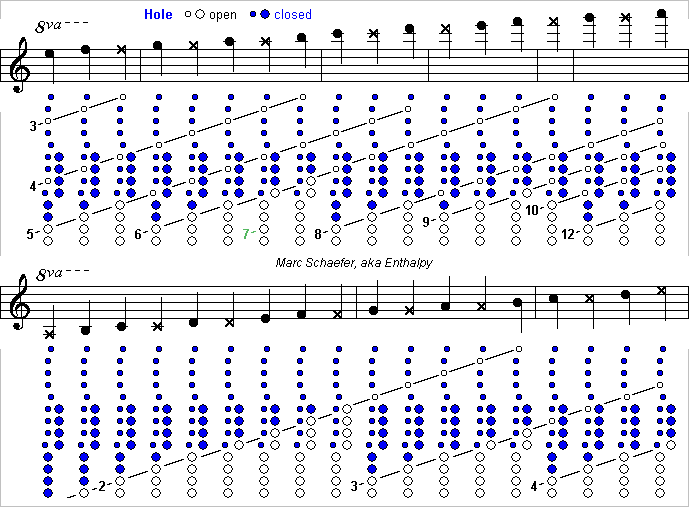

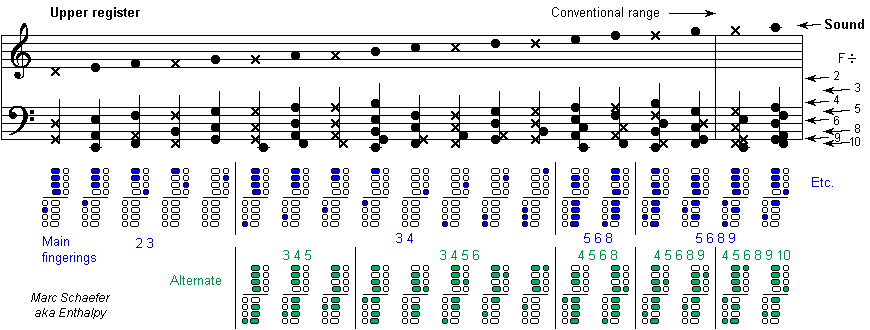

Here's a different attempt: a clarinet with automatic cross-fingerings. Other people proposed automatic cross-fingerings before. I suppose this instrument part wasn't from a flute http://memory.loc.gov/diglib/ihas/loc.music.dcmflute.1244/default.html but from such a clarinet, because (1) its 18 tone holes +end fit a clarinet (2) open holes some 9 positions apart make sensible cross-fingerings at a clarinet, not at a flute (3) the speaker key isn't desired at a flute but is at the usual position for a clarinet (4) a flute needs more flexibility to play the third octave (5) the missing length fits a barrel plus mouthpiece. This could also resemble a clarinet McIntyre system generalised to both hands, but movements resulting from two adjacent fingers suggest automatic cross-fingerings. I wish I could try the movements or have pictures from different angles. Opinions welcome! Here are already the fingerings I propose: The upper fingers close directly 8 tone holes, the thumbs on one more near the bell, all spaced by a halftone. The corresponding covers or rings act on more tone holes that I call "consequent": if the next higher hole is closed, an open finger hole permits to open two consequent holes 9 and 10 halftones higher. Mode keys at the thumbs choose which consequent hole to open, or both, or none. One open consequent hole 10 halftones higher vents the mode 5 in addition to mode 9 by the first open finger hole. This improves the reflection to play the highest register. One open consequent hole 9 halftones higher vents the mode 3 in addition to mode 5 by the finger hole. Upper second twelfth. Both closed to play the mode 3 by the finger holes. Lower second twelfth. Both open to play the mode 1 vented there. Upper first twelfth. Both closed to play the mode 1 vented at the finger holes. Lower first twelfth. At usual clarinets, the tone holes get narrow at the throat. They could be slightly wider as cross-fingering holes, and they should be to emit a clear upper first twelfth here through just two open holes. Though, narrow holes also increase the losses to match the reed and mouthpiece when the air column is short. I propose to put several smaller holes under one cover to reduce the inductance but keep the resistance of the higher holes - on other instruments too. Register holes are not displayed but necessary. The 10 halfnotes interval for mode 5+9 can probably emit a bad mode 3+5 too, so a register hole(s) shall impose the mode, just as for the lower second twelfth. More buttons at the thumbs can combine or not the action on consequent holes and on register holes. The lowest finger cover is also used alone or combined with one or both consequent tone holes. I'd put the same buttons at both thumbs, like the pinkies have at the Boehm clarinet. Some trills need extra hardware that paperwork can't determine. But one thumb tone hole more, plus its consequent hole, would solve that cleanly. Between modes 1 and 3, for Bb-C. One more hole above the consequent holes, own key. Between modes 3 and 3+5. Two more holes above the finger holes, with two keys? Between modes 3+5 and 5+9, combine the previous trill keys? These fingerings fit small clarinets better: the Eb, the Ab (or better high Bb for the repertoire). They need one joint for both hands, better including the barrel for a register key there. They limit the range to high D#, nice for a small clarinet but not for a bass. They let move 1+2+2 covers per finger, hence not too big ones please. And as small clarinets rely more on cross-fingerings, automatic keyworks with optimum venting ease them. With adapted intervals like modes 2+3 and 3+4, similar fingerings and keyworks would fit conical reed instruments: soprillo and sopranino saxophones, higher tárogatók, higher oboes, sarrusophones and rothphones, plus the ones I forget. Difficult keyworks hampered all attempts, but a sketch should come - later. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Fingerings

Here's a possible aspect of a clarinet with the Dec 25, 2017 fingerings. I miss the elegant and simple keyworks of the Boehm system. At least playing shall be easier. Projection follows the European method. Many background items are omitted. Right angles are only for simpler display. There are errors, certainly. Click for full size. The 17th hole is at the barrel's top as Sax and Marchi-Selmer did for the clarinet, not at the mouthpiece as Eppelsheim does for the soprillo. At the barrel, it is far too low for the top of 5*F register, but the 12th hole helps there. The Marchi system opened both keys and had a dual opening 17th hole: the reasons are expected to apply here. More register keys are possible, automatic ones too. The joints are as long as on the Boehm Bb clarinet with low Eb. The raise key, at the right thumb, is split in two but meant for simultaneous use: tolerances and assembling get easier, with only one transmission. The third button at right thumb closes the lowest cover. Some undisplayed means let hold the instrument at the metacarpus. The left hand is one tone higher than on the Bb Boehm, the right is as on the A boehm; it can be higher to shorten the upper raise key, but then the keys of right ringfinger and pinkie interact. At an Eb clarinet, some left fingers could close pairs of adjacent half-notes without covers, and the right hand use three rings. Though, I doubt a 17th key spares cross-fingerings at a small clarinet. Shallower or less narrow tone holes at the throat would ease the 5*F register without cross-fingerings, and split holes hopefully keep throat notes soft; this applies to the Bb instrument too. Lower instruments are easier, if accepting the range to altissimo C#. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Materials

Hollow parts of thin metal let also design wider hence stiffer parts. For instance the arms that hold the biggest covers of the baritone saxophone twist easily, and some brands build two arms per cover; taller wider arms would improve and still be light. Long transmission tubes as well can be too flexible, especially on contrabasses, and wider thinner tubes would improve. The (piston or rotary) valves and slides of brass instruments may be worth a try too. Thinner metal, electrodeposited or catalytically deposited, would make the complicated shapes lighter. The parts must be ground and run in, but could still be thinner than the present brazed tubes. Can bells, other parts or complete walls be made by thin electrolytic or catalytic metal deposition? Complex accurate shapes are easy. But does some alloy (or sandwich of alloys, as already suggested here) make good instruments? Ni (and supposedly Co, Sn, Ag among others) can alloy electrodeposited Cu. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Materials

Keyworks for woodwind (and brass winds) are made by casting (maybe forging too) of copper alloys: cups for the covers, arms... When the covers are large, notably on the saxophone, solid parts can be heavy. I propose to make them hollow and thin-walled hence light. Electrodeposition is a simple process for that, while catalytic deposition may be considered. It works easily with nickel, cobalt and their alloys, and more metals and alloys are possible, copper-nickel being known. The walls of almost arbitrary shape can be deposited on shapes of cast lead alloy that is later molten away. Other materials are used, including wax covered with graphite powder. Thickness exists down to 8µm but can exceed the mm. The process is easy enough for hobbyist to make parts for model boats, so a small music instruments company can learn it. Added layers can prevent allergies and corrosion, as is known. A first application could be the saxophone's neck octave key, which is presently slow because it's heavy, and rebounds sometimes. The musicians can replace it by themselves, especially if the pad is in place, so a company could sell the lighter replacement for instruments of varied brands. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Fingerings

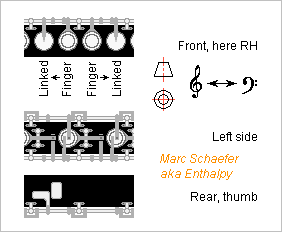

This is how the keyworks can raise the sound by a half-note on thumb action. Each of the eight upper fingers moves two linked covers to change the height by a full note. Additional holes make the half-notes; their covers are open at rest but often closed: when the thumb doesn't press the raise key; when the facing finger doesn't press its key; or when the next lower finger presses its key. The views use the European projection method. Rings can replace some covers, and some fingers can act at the higher tone hole position. The right thumb's button that closes the lowest cover is displayed but not its keyworks. The transition between RH and LH joints isn't accurate. All tone hole positions are open below the main transition. Zero or only one raising tone hole is open, if no cross-fingering is intended. Releasing one isolated finger for cross-fingerings would open two tone holes, or even three when using the raise key, bad - instead, additional speaker key(s) shall bring the altissimo register. Meanwhile I've read direct testimony that they do it on the Marchi clarinet and spare cross-fingerings. I've excluded some variants: The thumb must raise the sound when pressing. Release to raise would be inconvenient to play. But this demands springs acting against an other. The right thumb acts on both hands' tone holes, for easy transitions between the hands, and to leave the left thumb for the speaker keys. Opening all the raising tone holes below the transition would ease the keyworks, but the raise key's spring can't close eight covers. As described, it closes one, and the front fingers close the others - each front finger moves up to 4 covers. This system needs 1.5 tone hole per half-note. It seems to have more parts and links than a Boehm clarinet, but they are easily tuned, very uniform and mostly small and local. It saves most trill keys, the Boehm little fingers keyworks, has a single transmission between the RH and LH joints. The force needed from the front fingers must be optimized, and then this system looks very convenient to play. A clarinet drawing should come. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Fingerings

Here an attempt of fingerings for the clarinet family. The chart begins at Eb since most bass clarinets include it, and because a Bb soprano can then play scores for the A soprano. The tone holes are all open below the main closed-to-open transition. Timbre and intonation can be more even, and it solves the Boehm bass clarinet's flow noises, especially at the right middle finger's B. The speaker keys don't double as bad tone holes. Something lets hold the instrument at the right palm or at both so the thumbs are mobile. The left thumb moves no tone hole, only speaker keys, for instance three on the chart. Adolphe Sax had already put a speaker key at the barrel, outperforming the left index tone hole, and the Marchi system has it too with some refinements https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Page:Berlioz_-_Traité_d’instrumentation_et_d’orchestration.djvu/158 http://clariboles-et-cie.blogspot.de/2012/11/clarinette-selmer-systeme-marchi.html it shall be present here too. A single action could even open speaker holes near several pressure nodes if useful. Each of the eight upper fingers changes the height by a full note. The right thumb raises them by half a note, like the right index does for two notes on the oboe. A description of the keyworks should come. Register switches are easier than on the Boehm clarinet. Two trill keys are kept. All other trills use the normal fingerings. Only the thumbs must switch between buttons, the right one for two trills, which isn't difficult on the bassoon. Common Boehm clarinets use already the standard fingerings for the three first modes of the air column with good intonation: 1*F (fundamental), 3*F (12th) and 5*F (17th, opening the left index and right pinkie) up to the high F#. They use cross-fingerings for 7*F and 9*F, but the added speaker key on the Marchi system reportedly spares this: I'd like a fingering chart for the Marchi system, please! My fingerings are expected to ease the emission of 7*F and 9*F without cross-fingerings as they open all holes below the transition, but because they don't open isolated tone holes, they should make hypothetic cross-fingerings less efficient. If the wave reflection suffices, 5*F reaches the altissimo C#, excellent for the soprano. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Materials

Flexion damping by conducing heat through sheet thickness is inefficient because metal converts heat to work badly. Pure silver serving as an example: 1m*1m*1m heated by 1K stores 24kJ heat; It expands freely by 19µm or pushes 1.6MN if constrained, so it transfers 15J work or 600ppm to a matched load; Conversion from elastic energy to heat will be bad too and anyway <1; So the strain-to-strain conversion, which gives a damping with the proper phase, is tiny. Bad explanation of silver's damping on Nov 13 and 19, 2017. But the resonant frequencies stand. Since music instruments are full of excellent but unexplained features, the low-alloyed coppers and the alloy sandwiches may still be worth trying. Electrolytic deposition is an additional means to create a sandwich. Cu-Ni alloys are deposited by increasing the electrolyte's proportion of the less noble element and using enough voltage and current density Renata_Oriakova (425ko) Zr (-1.45V), Zn (-0.76V) and Cr (-0.74V) look difficult; Co (-0.28V) has nealy the same standard electrode potential as Ni (-0.25V) and should work too; Sn2+ (-0.13V) and Ag (+0.80V) lie closer to Cu (+0.34V) than Ni (-0.25V) is. I'd start from a laminated core and deposit the skins, which is decently quick for 100µm. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy Thanks for your interest! Quantify how good, not really... It is a matter of individual and subjective perception, and a sound can be qualified as good for a bagpipe but not for a clarinet. Or the same saxophone sound can be considered good for classical music but bad for jazz. What's worse: we don't even know presently what physical attributes of a sound makes its quality. Helmholtz had claimed "harmonics" and everyone followed for a century and even now, but he was wrong. A few people know presently that a musical sound is, and must be, non-periodic, so its harmonics can't define it. The perception of sound quality should, to my opinion, be investigated with a high priority. It's uncomfortable because outside harmonics and frequency response of linear systems, the toolbox of physics is quite poor - but that's what is needed. Analysing harmonics and filters have brought some interesting results for violins and wind instrument, but now it seems complete, and we know that this approach is insufficient. So presently, our ears are the only judge.

-

Woodwind Materials

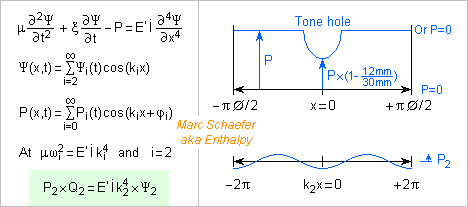

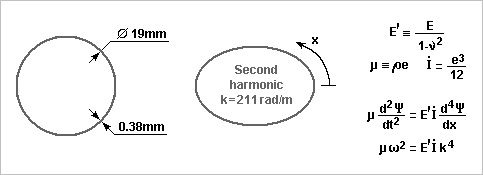

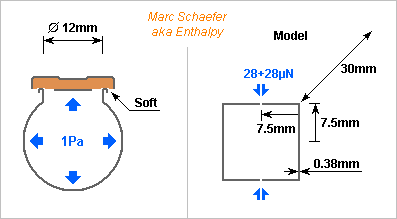

Here's a more formal model of the wall's elliptic deformation at the tone holes proposed on Nov 13, 2017. I keep neglecting the stiffening by the hole's chimney in metal bodies. If it stiffened perfectly 1/5 of the circumference on the whole body length, it would raise the resonant frequency by less than (5/4)2, nearer to 5/4. I keep the absence of pressure on the tube where the hole is, and because simplicity needs it, that the elliptic deformation is identical at the holes and between them. The deformation equation sums the forces on an element dx of the periphery for a unit length of tube. Zeta stands for the losses; heat conduction would include some complicated function of d2Psi/dt2 too, but later I represent anyway the losses by Q, the mechanical amplification factor at the considered resonance. The pressure felt by the walls, and the wall movement Psi, are defined over one circumference, so a Fourier series can represent them. Less usual than from time to frequency, this Fourier goes from the circumference position to the wave vector in rad/m. As the deformation equation is linear, the Fourier components of the movement and pressure distributions correspond, especially the second harmonic that makes the lowest resonance with an elliptic deformation. At a resonance, the µ*d2Psi/dt2 and E'I*d4Psi/dx4 compensate. If the mechanical amplification factor Q is not very small, the movement is Q times bigger than at low frequency where d4Psi/dx4 determines it. k4 comes from the differentiation of cos(k2x). A spreadsheet computes the second harmonic of the pressure distribution along the circumference for a 12mm hole in a D=19mm L=30mm tube section: WallsFourier.zip The sine peak value is P2=-0.098 times the air overpressure. Using: k2*pi*D = 4pi for the elliptic deformation, or k2=210rad/m; |P2|=-0.098 for 1Pa in the tube; E'=98GPa now for sterling silver and I=4.6*10-12m3 for 0.38mm walls; the wall moves by peak 0.11nm at low frequency and Q times more at a resonance. This is 1/4 the value estimated previously with a square tube model, and is possibly more accurate. ========== Mechanical Q=120 would now drop the sound's harmonics by 10% instead of Q=30. This isn't much for a metal: for instance a vibraphone bar resonates for seconds at hundreds of Hz, telling Q>1000 despite the radiation. Since we hear a tapped flute head joint of German silver resonate, a microphone and oscilloscope would tell figures. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Materials

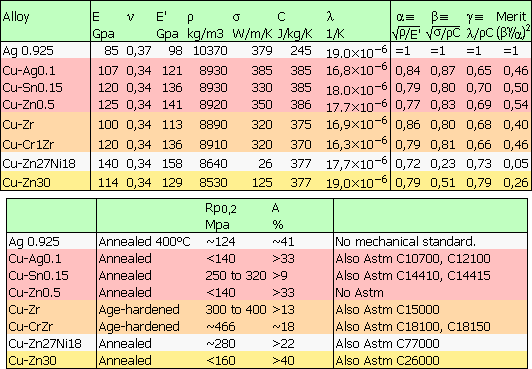

In the last message, I estimated a heat diffusion time through the whole wall thickness. But after diffusing through 1/3rd of it, heat reaches already a zone where flexion compresses and heats far less the metal, so this suffices for damping. Then, the diffusion time is only 1/9th or 0.1ms, which equals a quarter period for maximum damping at 2500Hz, in the resonance range of the 0.38mm silver walls. Strong coincidence again. ========== I've computed some figures of merit to compare alloys for damping resulting from heat diffusion. All refer to sterling (92,5%) silver, whose data comes from Doduco and Substech since mechanical engineering forgot to standardize it. Alpha tells how thinner walls can be if a stiffer or lighter material keeps the resonance frequency. Beta represents the heat diffusion distance at a given frequency. Gamma shall represent the heat-to-elongation or elongation-to-heat couplings. Possibly incomplete. The global figure of merit squares gamma since damping results from elongation-to-elongation, and also beta/alpha like a heat sine diffuses. From the table, sterling silver has the best combination to dampen vibrations by heat diffusion. Brass is bad and German silver much worse. Elemental silver's main advantage is the low heat capacity per volume unit, equivalent to a big molar volume for a metal: https://www.webelements.com/periodicity/molar_volume/ https://www.webelements.com/periodicity/youngs_modulus/ https://www.webelements.com/periodicity/coeff_thermal_expansion/ Strong thermal expansion goes rather against stiffness for pure elements, but atypical alloys exist like Invar, so it would be worth checking. Gold, platinum, rhodium are sometimes used, but their figure of merit is worse than silver, based on incomplete data. I've added high-copper alloys uncommon in instrument making. The last two need age hardening to conduct heat well; is it compatible with fabrication and maintenance methods? The figures of merit aren't as good as silver but far better than German silver and the alloys are cheap. Plated against corrosion, would they make better student's flutes? The company Gévelot supplied electric igniters whose wires could be bent sharply tens of times without hardening, while electric copper would break. I ignore the alloy, but instrument makers may like it or an adaptation. Some alloys in the table are too hard, so they could be less alloyed to improve the heat conductivity. Rolling a sheet 60mm wide uses affordable equipment, and a quick test would be to solder a tube and tap it to compare the damping with silver. ========== A sandwich can combine a stiff alloy as the skins, ideally with a big thermal expansion, and a conductive alloy as the core. In the above table, brass can cover little alloyed copper, with thicknesses like 15%-70%-15%. Deep-rolling hot sheets can join them besides explosion welding. The sandwich dampens hopefully more than brass and is stable enough for a saxophone. Ceramics are stiffer than metals and polymers expand more, but having both isn't obvious, and craftsmen prefer metals. A lacquer maybe, if easily removed and reapplied, and if some filler makes it stiff? ========== Other damping processes exist in alloys. For instance a Cu-Mn is known as a damper: try it a music instruments? Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Materials

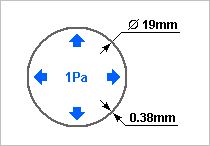

Can a physical model justify the wall material's debated influence? I take a flute as an example because I know dimensions; a piccolo or a saxophone would be interesting too. Most people consider a cylindrical closed tube: A usual argument is that 1Pa air overpressure in D=19mm and for instance L=30mm (a distance between tone holes) squeeze adiabatically 6*10-11m3 more air in the column, while the resulting 25Pa stress in the 0.38mm E=83GPa silver walls strain them by 0.3ppb and increase the contained volume by 5*10-15m3, or /104, so it's negligible. Here I suggest (I'm probably not the fist) a more significant process through resonance and oval deformation. I apply known models for flexural waves in sheet (E'=96GPa for pure silver, rho=10490kg/m3) to the cylindric wall. Its deformation is represented by a Fourier series where the fundamental is meaningless and the upper harmonics uninteresting, leaving the second, where kx covers 4pi in one geometric turn. With 0.38mm thickness (0.45mm is common too), the oval deformation resonates at F=2342Hz, just one note above the official range of the flute. So the fundamental doesn't excite this resonance (it can't be chance) but the harmonics may. How can such an oval mode couple with the air pressure? I exclude offhand the circle imperfection of the body, because tone holes offer a stronger coupling. Where the instrument has a hole, the wall doesn't receive a balanced force. It could be an open hole, if the air keeps a significant pressure at that location, or beneath a cover or a finger, which get a part of the force. As the pad or finger are much softer than the wall, they vibrate separately without transmitting the missing force to the wall. From 1Pa overpressure, 112µN push a D=12mm hole cover instead of balancing the forces on the wall. As balanced forces have no consequence, the effect is the same as 112µN alone pushing down on the wall's top, and since the whole body can accelerate freely, the deformation is similar to 56µN pushing towards the centre at the wall's top and bottom. The hole's chimney stiffens the body on 1/5 of the circumference and on 12mm over 30mm body length. This raises the resonances a bit, offering many proper frequencies to the sound. I neglect this stiffening for simplicity. Taking a Fourier transform of the force distribution and solving on the cylinder for the second harmonic would have been more elegant. Instead, I model the closed cylinder as a 15mm*15mm square of same circumference, slit where the forces apply. On 30mm length, 28+28µN and 7.5mm arm length bend E'I=0.013N*m2 by 0.12µrad over 7.5mm height, so the centre moves by 0.9nm - but half without the slit, or 0.45nm. The oval deformation changes the volume little at the closed section, but at the decoupled cover it makes 5*10-14m3. That's 1200 times less than the air compressibility, without resonance. Now, metal parts resonate, often with a big Q-factor. Take only Q=40: the volume due to the wall vibration is only 30 times less than the air compressibility. And at the resonance, the volume increases when the pressure peaks: it acts as a loss, not like extra room. This effect may be felt. With varied hole spacing, the flute offers many different wall resonances. The computed 2342Hz is for instance the 3rd harmonic of the medium G, so it has 12 quarterwaves in the air column. For this frequency and column length, the radiation losses alone give Q=60 and the viscous and thermal losses alone Q=138, summing for Q=42 without any other loss at the pads, the angles etc. If the wall resonance adds its Q=30 at one 30mm section from 440mm air column, the combination drops from Q=42 to 38, or 10%. Harmonics and partials change the timbre and the ease of emission. We're speaking about small effects anyway, so this increased damping of the harmonics may explain the heard and felt difference. ========== If you tap a flute's body with a plastic rod, German silver makes "ding" while silver makes "toc", a strongly damped sound. Silver's smaller mechanical resonance would attenuate the harmonics less, providing the reported easy emission and brilliant sound (...that I didn't notice at the Miyazawa headjoint test). This isn't necessarily a bulk property of silver. Thin sheets dampen bending vibration also by thermal conductivity: the compressed face gets warmer, and if some heat flows to the opposite side, less force is released when the compressed face expands. For 0.38mm thickness, a typical heat diffusion time is 0.8ms, just a bit long for the body's oval resonances, so thinner silver would attenuate more the mechanical vibrations hence less the sound's harmonics, but its resonances would fall too low. 0.45mm raise the resonance frequencies but strengthen the mechanical resonances. Again, this is consistent with the choice of silver for heat conductivity, and with the wall thickness. It's also consistent with the tried red brass for saxophones. But as PDM conducts probably less than sterling silver, it must bring other advantages. An alloy with a big thermal expansion (but good heat conductivity) should make a damping sandwich around a conducting silver core. I didn't find practical elements (indium 32ppm/K, zinc 30ppm/K) but alloys may exist. Laminate together with silver, or weld by explosion, as usual. Total 0.4mm stay good, most being silver. ========== Grenadilla (Dalbergia melanoxylon) is less stiff: 20GPa lengthwise hence maybe 2GPa transverse. But it's lighter hence thicker, like 1310kg/m3 and 3mm. The same resonance jumps to 14kHz. To my eyes, a good reason that high notes around 2kHz are easier. I've no data about damping at interesting frequency for transverse bending. Grenadilla gets scarce, and different wood is less stiff. Plain polymers offer isotropic 2 or 3GPa and the same density and thickness. Damping and lengthwise stiffness may distinguish them from wood. Polyketones are known dampers, worth a try? Polymers loaded with short graphite fibres are available industrially, notably POM and ABS. They offer 1470kg/m3 and isotropic 10GPa, very seducing. Graphite isn't very abrasive to cutting tools. Give them a try, including at bassoons and oboes? Long graphite fibres in epoxy matrix exist for flutes (Matit). If filament winding isn't already used, it's easily tried, since small companies make tubes on request. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Materials

Here are some observations I made about wall materials for woodwinds. ========== The most reliable experiment was with flute headjoints on a concert instrument by Miyazawa, who sent the flute to a distributor in my city for the trial. Two professional flautists were invited together with me. They abandoned the trial and preferred a smalltalk after half an hour, so I could try the hardware alone for the afternoon. The room was mid-small, with carpet and some furnitures, at comfortable temperature and usual humidity. I was in an investigative mood, I believe without prejudice. Myazawa put at disposal a flute body with perfectly adjusted keyworks, whose intonation and emission beat the new Cooper scale, and three headjoints of shape as identical as possible, of - silver-plated German silver - plain 92.5% silver - their PCM alloy. All differences are small. The temperature of the headjoint is much more important than the material. Playing music wouldn't tell the differences within the test time: I provoked the known weaknesses of the Boehm flute. After 20 minutes, I could detect differences and reproduce them with confidence. Plain silver is identical to silver-plated German silver, or at least the differences are uncertain. Silver might make more brilliant medium notes. PCM improves over silver. The highest notes of the 3rd octave (and the traditionally unused 4th) are easier to emit pianissimo, and they sound less hard consequently. The instrument's lowest notes can be louder and their articulation is easier. I can't be positive that the medium notes are more brilliant. We avoided comments during the trial. One other flautist coincided exactly with me, the other had no opinion. So while materials do make a subtle difference, switching from German silver to silver headjoints as a flautist progresses is just superstition and marketing. Manufacturers may use silver for their better handcrafted products. I ignore if silver is easier to work and enables different shapes, but its acoustic qualities are identical to German silver, a cheap alloy of copper, nickel, zinc. The better PCM is darker than plain silver, rumoured to contain less silver and be cheaper. I believe up to now that the wall material matters most at the tone holes, hence at the body more than at the head joint. Testing that would be uneasy, since identical shapes are more difficult at the body, and the cover pads matter more than the walls. ========== I tried once a flute of gold, pure or little alloyed according to its colour. It was only a typical new Cooper scale, with very low 3rd G# and imperfectly stable 3rd F# - poorly made in France with very bad short C#. It didn't even have the split E mechanism, so the 3rd E was badly unstable. The lowest notes were weak, the highest hard and not quite easy. With such a thing, I couldn't concentrate on the claimed acoustic qualities of the metal and stopped the trial very quickly. At least, they didn't squander scarce wood for that. ========== Some piccolo flutes have grenadilla or silver headjoints, at Yamaha and elsewhere, on a grenadilla body. Wood is so much better that telling needs no frequent switches in a long experiment. The highest notes are easier to emit piano hence sound less hard. The lowest notes stay bad as on a piccolo. Wood (and plastic) offers other manufacturing possibilities than metal sheet. Especially, undercutting the blow and tone holes is easier. This may explain a good part of the improvement. The temperature profiles of the air column can't match between a wooden and a metal head, so "identical shapes" would be meaningless anyway, as harmonics aligned for one material would be misaligned with the other. Was the design optimized for wood and kept for metal? At least, the comparison stands for other manufacturers. ========== I tried a modern grenadilla flute from Yamaha around 2004. I found it fabulous. While metal concert flutes don't differ so much, this instrument has by far the strongest low notes of all the flutes I've tried - a very much desired improvement - and the easiest pianissimo on the highest notes. Its sound is very mellow, what soloist seeking a "good projection" hate but saxophonists switching the instruments like. Did the material alone make the difference? I don't think so. At Mönnig the wooden and metal flutes played about identically. This flute had also a new scale (holes' position and diameter) since its 3rd F# was more stable and its 3rd G# intonated almost perfectly. The mellow sound may result from the scale, as for a flute I tried in a Parisian workshop, and the stronger low notes from wood's workability like undercutting, or from a wider bore locally. ========== Despite playing the saxophone, I was once called to try a clarinet of thin injected thermoplastic. Its covers were of injected thermoplastic too, with modified movements, and I don't remember the more important pad material. The effect is huge, and people who claim "the material has no influence" should try that. The cheap and easy instrument offered as little blowing resistance as a soprano sax, consistently with huge losses, and couldn't play loud. The timbre suggested a clarinet, but, err. ========== Comparative trials abound on the Internet but many ones about flutes are obviously fiddled so the hearer notices a difference. Remember on the Miyazawa, it took long to notice any difference; much was about the ease of playing, and the subtle sound differences wouldn't survive computer loudspeakers. These shall be oboes of grenadilla versus cocobolo, both from Howarth https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yVouYVlDZDY and if the construction is identical, then the material's influence is (not unexpectedly) huge on an oboe. In short, cocobolo makes bad oboes of clear and weak sound. Grenadilla (Dalbergia melanoxylon) gets ever scarcer while cocobolo (Dalbergia retusa) is abundent, but cocobolo slashes the density by 1.4, the longitudinal Young's modulus (I'd prefer the transverse) by full 2.0 but increases damping by 1.5 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00548934/document (9MB, in French, p. 117)

-

Woodwind Fingerings

Here's a possible aspect of the piccolo reed instrument. I've drawn a single reed instrument because the rare Ab clarinet achieves the target range and its reeds exist in catalogues, while I doubt oboists' lips survive one octave more. The apex of the conical bore must be truncated very little. The miniscule reed imposes some small susceptance, but the mouthpiece's volume must be reduced. A double reed would help here. Like a clarinet but unlike a saxophone, the mouthpiece fits in the body with no additional volume. The reed seat of an Ab clarinet mouthpiece may fit the task; the longer instrument permits more tip opening with softer reeds. To ease the piccolo flute's high notes, thick grenadilla walls beat metal, hence grenadilla here - or polymers, I still have no opinion. The section from the mouthpiece to the thumb keys is more easily bent, for instance to make a sopranino of decent size. Here a piccolo is as long as an oboe. The result resembles a narrow, higher pitched tárogató. Call it a gatito? I omitted on the sketch many items where partly hidden. Other are over-simplified, for instance four movements need four shafts or two pairs. And, well, there are probably some mistakes. The keys that make the cross-fingering holes closed at rest to ease the fingerings put the holes behind the hands on my sketch. Improvement would be welcome. Here 4 tone holes on the upper joint are closed at rest and 4 on the lower are open at rest. This lets transmit 4 movements. 5+3 holes are possible with a slight fingering change and a longer wooden main joint. The holes brought by Stowasser are closer to the bell's rim on this higher instrument. If the cross-fingering holes double-serve as tone holes, they can reach without gap the first mode pedal tones, but the instrument must favour the highest modes through the bore width, reed and mouthpiece size, position and size of the holes. Marc Schaefer, aka enthalpy

-

Woodwind Materials

Hello everybody! The material used for the walls of woodwind instruments, and its real, perceived, imagined or absent influence on the sound and ease of playing, has been and is the controversial matter of recurrent discussions that I gladly reopen here. The air column is the essential vibrating element of a wind instrument, the walls are not, but this is only a first analysis. The walls are commonly made of wood (sometimes cane, bamboo etc.), metal, or polymer aka plastic, which manufacturers call "resin" to look less cheap. Mixes exist too, with short reinforcement fibres or wood dust filling a thermoplastic or thermosetting resin ("Resotone" for instance). I'm confident that long graphite fibres were tried too, as fabric, mat or in filament winding. The choice results from marketing, tradition, weight and manufacturing possibilities (a tenor saxophone is too big for grenadilla parts), cost - and perhaps even acoustic qualities. ========== Plastic is a direct competitor for wood, as the possible wall thickness, manufacturing process, density, stiffness, shape possibilities, are similar. As opposed, the density of metal restricts it to thin walls made by sheet forming an assembling, but permits big parts. Manufacturers typically use plastic for cheaper instruments and grenadilla for high-end ones - some propose cheaper wood in between, possibly with an inner lining of polymer. Musicians who own a grenadilla instrument disconsider the plastic ones; I never had the opportunity to compare wood and plastic instruments otherwise identical, so I can't tell if the materials make a difference, or if grenadilla instruments are more carefully manufactured and hand-tuned, or if it's all marketing. Two polymers are commonly used: polypropylene for bassoons, and ABS for all others, including piccolos, flutes, clarinets, oboes. These are among the cheapest polymers, but 10€/kg more would make no difference. They absorb very little humidity, but some others too. More surprising, they are uncomfortable to machine: POM for instance would save much machining cost and (my gut feeling) easily pay for the more expensive material. But ABS and also PP absorb vibrations while others don't, which I believe is the basic reason for this choice. They limit the unwanted vibrations of the walls. As a polymer that dampens wall vibrations, I should like to suggest polyketone https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polyketone it's known to make gears more silent than POM and PA, its glass transition is near ambient temperature, its density and Young modulus resemble ABS, it absorbs little humidity. Still not widely used, it can become very cheap. Its creep behaviour and ease of manufacturing are unknown to me, but ABS and PP aren't brilliant neither. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Fingerings

Many high-pitched woodwinds, say one octave over a soprano, were tried. Only the piccolo flute is commonly used. The others are quite difficult to play, because the reed is too small and because the emission and intonation are bad and the timbre very hard. At least the timbre and intonation result from the too short air column, which doesn't filter enough the high harmonics and is exceedingly sensitive to the reed's susceptance. Switching from C# on the saxophone's first register to the next D on the second register improves both, by resonating the second mode of a longer air column (this improvement results also from losses matching the reed and mouthpiece better). So I propose to build high-pitched woodwinds that use only the second mode and higher, consequently with a longer tube. A cylindrical tube would look very long for a high-pitched instrument, so I describe conical instruments like the tárogató, saxophone or oboe - extrapolation is easy. Sopraninos would be feasible but as long as altos. A piccolo is as long as a soprano to play an octave higher. As the pitch demands, the bore is very narrow, especially as compared with the length. The modes 2 and 3 are closer to an other than 1 and 2, so fewer tone holes suffice. Fine, since my proposal has extra holes to use cross-fingerings on most registers so high notes reflect well and are easy to emit. Here's a description of the holes and fingerings. 8 tone holes make only the main closed-to-open transition for 9 notes and overtones; the sketch doesn't show the unused mode 1. 6 holes suffice if the higher registers begin at the bell as on the clarinet, but that's uneasy. The holes are narrow enough for a soft timbre, wide enough to emit the higher registers in tune, evolving with the position: similar to a clarinet. Both thumbs operate them all alternately with 8 keys, like the little fingers on the Boehm clarinet. The already described keyworks http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/107427-woodwind-fingerings/?do=findComment&comment=999559 synchronizes the covers. The four higher covers can be closed at rest and the lower four open at rest. A separable joint with the lower four holes (and four transmissions) is one natural choice. The narrow bore and the small reed and mouthpiece shall excite the second mode when only these holes are open. One optional long and narrow octave hole, operated for instance by the right index' proximal or middle phalange, would stabilize this mode. A separate set of 9 cross-fingering holes combine with the tone holes to produce the upper registers. They are independent with one finger each, except that for instance the left index operates also the highest hole with the proximal or middle phalange. Covers closed at rest ease playing, though coverless holes are cheaper. These holes are narrower to reflect the wave partly: only several holes including the tone holes make a good reflection. They must also be lossy enough to spoil the unwanted modes and can consist of several narrower holes under a common cover. Four tone and cross-fingering holes can occupy nearby positions at the tube, though three works too. The cross-fingering holes are expected nearer to the pressure nodes and the half-wide tone holes higher on the tube. Here blue means a closed hole. The corresponding key action varies. The number of lone open holes increases regularly with the modes: Zero for mode 2 (but optional octave hole) One for modes 2+3 and 3+4 Two for modes 3+4+5, 4+5+6, 5+6+8 and 6+8+9 Three for modes 8+9+10+12 The reflection improved by more open holes eases the emission of high notes. The low-intonating mode 7 isn't used; combine with the slightly high modes 6 and 12? The fingerings don't limit the range; written F# is already ambitious. An aspect sketch and hints to the construction may come some day. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

I stand by my figures, especially the thrust versus concentrator size. Whether they fit the decisions and policies of an administration is no proof for anything. Nor do I need nor seek bad designs elsewhere to consider them as limitations for other attempts. I'm not interested by a refractor concentrator. No perceivable usefulness, so its mass and losses are no hint to anything. Yes, more Isp needs more power. The sunheat engine allows to adjust the trade-off in flight, but I've seen no clear usefulness. From the trials cited in 20160003173.pdf: An inflatable concentrator is bad for high focus temperatures. I take a rigid one. Several concentrators per engine are dangerous for the craft or vessel and difficult to test. Sunlight can't make the proper temperature on Earth. How did they figure such a thing? Their results reflect that. Their nozzle is too small. They have no ruminator. It remains to see if their colder faceplate radiates little, and how much heat is lost through conduction to the faceplate. I don't understand the alleged advantages of the refractive secondary concentrator. But its obvious drawback is to limit the temperature. The Isp improvement through dissociation results from absorbed heat primarily, not from the average molecular mass. Their mass estimates are way off. A Gso launch does save a lot through sunheat engines. Yes, fairings must increase. Or better, make a separate sunheat stage, as I suggested here. They only consider Leo-to-Gso missions, too bad. => Many bizarre choices, misconceptions and half-thought designs. This led to wrong conclusions. => This is why I don't seek figures elsewhere to decide if a potential technology is interesting. Concentrate light on solar cells: The light is filtered by wavelength, and then the efficiency of the solar cell is hugely better. 40% refers to the power intercepted by the concentrators. Light with bad wavelength is rejected. When used at Saturn or even Neptune, no overheating to fear. Not only is the sunheat engine extremely performant, it's also the sole and only solution beyond chemical propulsion.

-

Woodwind Fingerings

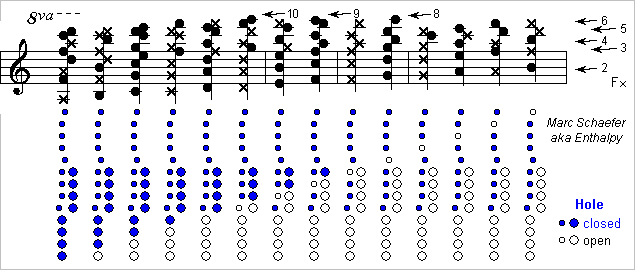

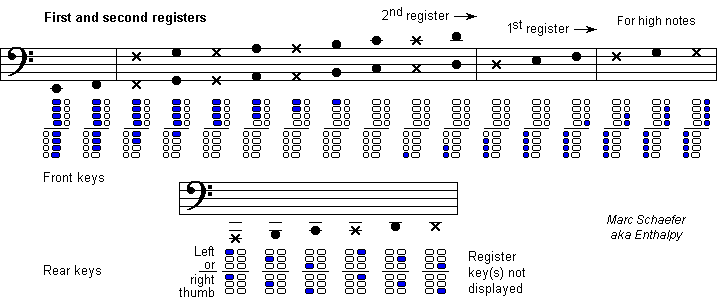

The bassoon is by far the woodwind most in need of better fingerings, but also the most difficult to improve https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bassoon Heckel made the last significant change a century ago. It starts at Bb like many woodwinds but the second register begins higher and toneholes go to F, so the first register spans 20 notes plus Heckel's three holes for high notes. Its cross-fingerings span a major twelfth for a total of three octaves and a major sixth - the official range for which standard fingerings shall intonate decently; most bassoonists tell "four octaves", "four and a half", or "five". Many of the tone holes are tiny; some are very long too (about 60mm, almost a quarter wavelength at high notes) hence inductive and sit consequently very high on the tube, working almost like an ocarina. Consequently, the bassoon has the most complicated keyworks, with many connections, alternate fingerings, and keys where you don't expect them. A fingering chart for the Heckel system: http://davidawells.com/resources/fingering-charts/ 9 and 4 keys at the thumbs, so charts show the left front, left rear, right front and right rear keys - part of bassoonists' snobbery. Note the flicked keys, half-open hole, four keys pressed simultaneously by one finger, resonance keys, numerous holes closed at rest, a cover for three tiny holes at once, and writing on bass, tenor and treble keys. Detailed views there: http://www.clarissono.de/CssArchiv/CssTerminologie/CssTermFagott/FagottTerminologie.pdf This is how the range splits, including 16 holes able to open while the next lower is closed: These fine people tried to put big tone holes at the proper places, often on a wider bore, and didn't succeed: Triebert. His failed bassoon attempt is exposed at the Brussels museum. Sax. His failed bassoon attempt is exposed at the Paris museum. Gautherot. His sarrusophone sounds... It doesn't resemble a bassoon. Guntram Wolf, during the computer era. He didn't market his bassoforte. So let's see what can be done with the narrow tone holes and bore that double reeds demand. But since I want no closed tone holes below the closed-open transition, the hole positions and dimensions (aka "scale") will differ. This affects cross-fingerings and needs an important development time. Hole diameters and lengths should vary slowly with the position. Consistent sound quality needs narrow holes at the throat, but I'd have holes of decent length with predictable effect on high notes. Presently, inductive holes let the beginning of the upper register sound half a tone higher than flute logic tells; could this be a tuning goal? ========== Here each upper finger closes one cover open at rest or opens with the proximal or medium phalanx one other cover closed at rest. The second set of keys is adjusted to each musician. Each thumb can close 1 to 6 of the lowest covers, so the musician alternates the thumbs like little fingers on the clarinet. Both thumbs manoeuvre the register key(s) too; adding some near the reed shall help play the contraforte http://www.guntramwolf.de/downloads/contraforte_e.pdf Does a fourth tone hole fit at the wing joint's top? Then all the fingerings can slip half a tone higher and the thumbs manoeuvre one cover more. Here are fingerings for the first and second registers. And these would be fingerings for the upper register according to simple flute logic which the bassoon does not follow due to its narrow tone holes: it tends to play cross-fingerings half a tone higher or more. So the diagram is merely an indication that these fingerings offer flexibility for cross-fingerings and cover the whole range - they even overlap nicely. The Heckel bassoon needs action at the thumb covers for some high notes. With thumb covers all open, I hope it's unnecessary here. As this fingering is highly regular, it lets choose a steady progression of hole diameter, length and position, which shall permit sound colour, ease of playing and intonation uniformly good. ========== I'm half pleased with the bassoon fingerings I propose here. They need many transmissions between the joints. Don't disassemble the instrument and fold it more? But I like the bassoon shape. Are they convenient? Unclear to me, and difficult to assess on the paper. But they bring holes all open below the transition, positions and diameters of tone holes that vary regularly, fully flexible and regular cross-fingerings for the upper register. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Bore width of wind instruments

An other bassoonist playing the same sonata on a Heckel system instrument: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=joKtwJL1Xq8 He has a softer sound (and plays damn well too). The difference with the narrower French bassoon remains.

-

Woodwind Fingerings

The cor anglais and baritone oboe have a pear-shaped bell https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cor_anglais https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bass_oboe and to my ears, the resulting sound is seducing for five minutes but boring thereafter. So I suggest, independently of the fingerings, to build them with the oboe's conical bell to get its narrow dark sound, and soften the lower notes using the same small holes near the bell as the tárogató has, as depicted there: http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/107427-woodwind-fingerings/?do=findComment&comment=1004315 Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/76627-solar-thermal-rocket/?do=findComment&comment=1007124 Where did you see such a thing? A strong electric engine? Why?

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

To accelerate a craft for weeks, the sunheat engine uses an energy amount impossible to store. But to raise or lower an apoapsis, escape a celestial body or get captured, the smaller energy for short kicks can be obtained during idle time and stored, as already noted on Jun 10, 2014: http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/76627-solar-thermal-rocket/?do=findComment&comment=810218 More details now. ========== Lithium-polymer batteries can store 475kJ/kg more or less. Before a kick, the concentrated light can be split by wavelength and sent to small solar cells of varied bandgaps for >40% conversion. http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/76627-solar-thermal-rocket/?do=findComment&comment=826983 Other uses welcome the efficiency and collecting area far from the Sun. To raise the apoapsis in Earth orbit, each sunheat engine without storage consumes 20kW during 1200s. A battery providing as much energy to double the force weighs 50kg. That's worse than adding one ~30kg engine. But: Fewer engines are easier to deploy. Operation during an eclipse season gains time and provides flexibility. Electric pumps for the propellants making the escape chemical kick justify 100-150kg batteries if starting with 18.5t at Leo, so 8 sunheat engines get 30% more energy per kick at zero extra mass, and the added thrust can concentrate on the best 1000s. At Mars (1.52AU) the battery is already lighter than the additional engine, at Saturn (9.58AU) the battery advantage would be 50*, if 1200s kicks were meaningful there. Other uses cherish the good electricity production at the outer planets. 700W from 8 concentrators at Saturn. The combination isn't a resistojet, because direct heating by sunlight is kept, as it avoids the wasteful conversion to electricity. Far better for the long pushes. The engine can use the same chamber for both modes or not. The described regenerative insulation methods apply. ========== Melting a metal stores heat too. Simpler than making electricity first, but heavier, and they probably dissolve their tungsten container. Tmelt Hmelt K kJ/kg ------------------- 3290 Ta 159 2896 Mo 286 ? 2750 Nb 288 2506 Hf 143 ------------------- One hope is to find some eutectic of tungsten with one or several other elements giving the desired melting point, as inspired by Sn-Pb-Ag solder not dissolving Ag. I didn't find credible data about Hf-W nor Nb-W eutectics, only calculated data; Mo-W and Ta-W seem to make no eutectic and be fully miscible. ========== Melting a ceramic stores more heat. Beware data is inconsistent. BeO is toxic, and B is expected to corrode W. More complex formulas are possible. Mixes shall bring missing melting points. Tmelt Hmelt Hform K kJ/kg kJ/mol --------------------------- WO2 -285 Ta2O5 -409 NbO -406 --------------------------- 2988 ZrO2 706 -550 2915 MgO 1920 -602 2703 SrO 674 -592 2500 Y2O3 463 -635 2318 Al2O3 1071 -559 2247 ZnO 860 -351 2218 MnO 767 -385 --------------------------- The last column shows the heat of formation per mole of oxygen atoms. If the melt's metal binds more strongly with oxygen, it could be compatible with W; computing the chemical equilibrium would be better if data exists. For water propellant at a lower temperature, container candidates are Nb or better Ta, possibly with W coating on the melt side, and some ceramics. As heat storage keeps the engines hot for months, the temperature should rather be 2700K or 2600K. With the ceramic fully molten, 2800K remains possible during week-long accelerations. MgO stores 4* more energy than a battery and is 2* lighter than an added engine for perigee kicks. The advantage increases at the outer planets. ========== The freight transport to the Moon took 10 months of perigee kicks with 10 sunheat engines http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/76627-solar-thermal-rocket/?do=findComment&comment=1007124 Let's replace 4 sunheat engines by 120kg of MgO heat storage: the 1.55* stronger kicks gain 3.5 months, and thanks to the shorter kicks' efficiency, we land 2% more mass. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

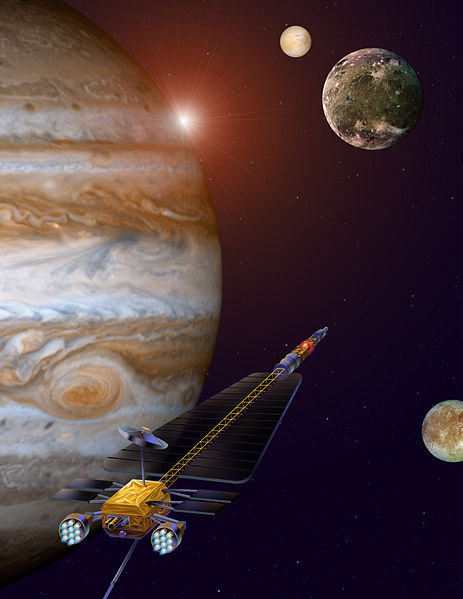

Solar Thermal Rocket

Electric thrusters need so much power that solar panels feed only a faint push. Operations near a planet, which takes stronger engines, lead to use a nuclear reactor which can't be very light and needs a big radiator. The cancelled Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter Jimo (not the Explorer Jime) was such a project, and this drawing (thanks to Nasa) illustrates the oversized feeder for the electric engine: The reactor is at the tip, the "wing" is the 422m2 heat radiator, and from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jupiter_Icy_Moons_Orbiter the science payload orbiting Europa, Ganymede and Callisto would have been 1500kg, similar to what the sunheat engine promises - but Jimo would have needed chemical engines to leave Earth, so despite the electric thruster's higher Isp, it would have weighed 36t in Earth orbit launched in three heavy flights and cost 16G$.

-

Quasi Sine Generator

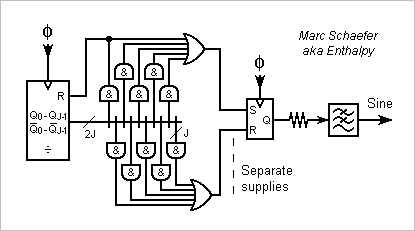

Hello you all! Here's a means to produce a sine wave voltage, very pure, with metrologic amplitude, whose frequency can be varied over 2+ octaves in the audio range - this combination may serve from time to time. It uses sums of square waves with accurate shape and timeshift. A perfectly symmetric square wave has no even harmonics. Adding two squares shifted by T/6 suppresses all 3N hamonics as the delay puts them in opposition; this makes the waveform well-known for power electronics. Two of these waveforms can be added with T/10 shift to suppress all 5N harmonics, then two of the latter with T/14 shift, and so on. A filter removes the higher harmonics as needed. The operation makes sense, and may be preferred over direct digital synthesis, because components and proper circuits may provide superior performance. Counters produce accurate timings. If a fast output flip-flop outputs a zero 1ns earlier or later than a one, at 20kHz it leaves -90dBc of second harmonic and at 1kHz -116dBc, but at 1MHz less interesting -56dBc. If the propagation times of the output flip-flops match to 0.5ns, at 20kHz they leave -100dBc of third, fifth, seventh... harmonic and at 1kHz -126dBc. 74AC Cmos output buffers have usually less than 15ohm and 25ohm impedance at N and P side. On a 100kohm load, the output voltage equals the power supply to +0 -200ppm. 5ohm impedance mismatch contributes -102dBc to the third harmonic, less at higher ones. Common resistor networks achieve practically identical temperatures and guarantee 100ppm matching, but measures give rather 20ppm. This contributes -110dBc to the third harmonic, less at higher ones. This diagram example would fit 74AC circuits. Programmable logic, Asic... reduce the package count and may use an adapted diagram. To suppress here the harmonics multiple of 2, 3, 5 and 7, it uses 8 Cmos outputs and resistors. As 3 divides 9, the first unsqueezed harmonic is the 11th. A counter by 210 has complementary outputs so that sending the proper subsets to 8-input gates lets RS flip-flops change their state at adequate moment. Programmable logic may prefer GT, LE comparators and no RS. I would not run parallel counters by 6, 5 and 7 instead of 210 as these would inject harmonics. The RS flip-flops need strong and fast outputs. Adding an octuple D flip-flop is reasonable, more so with programmable logic. I feel paramount that the output flip-flops have their own regulated and filtered power supplies, for instance +-2.5V, and the other logic circuits separated supplies like +-2.5V not touching the analog ground. That's a reason to add an octuple D flip-flop to a programmable logic chip. For metrologic amplitude, the output supplies must be adjusted. All the output flip-flops must share the same power supplies, unless the voltages are identical to 50ppm of course. A fixed filter can remove the higher harmonics if the fundamental varies by less than 11 minus margin, and a tracking filter for wider tuning is easy as its cutoff frequency is uncritical. The filter must begin with passive components due to the slew rate, and must use reasonably linear components. ---------- I tried almost three decades ago the circuit squeezing up to the fifth harmonic, and it works as expected. Squeezing up to the third is even simpler, with a Johnson counter by 6 and two resistors. Measuring the spectrum isn't trivial, for instance Fft spectrometers can't do it; most analog spectrometers need help by a linear high-pass filter that attenuates the fundamental. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Fingerings

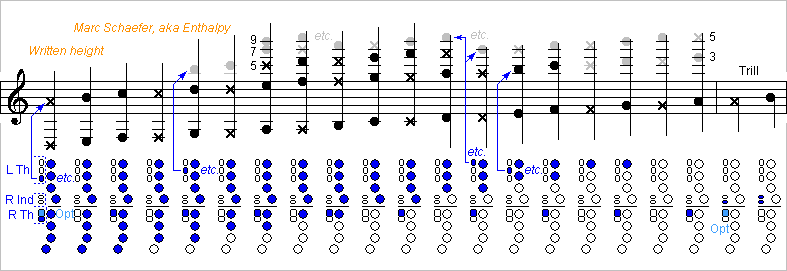

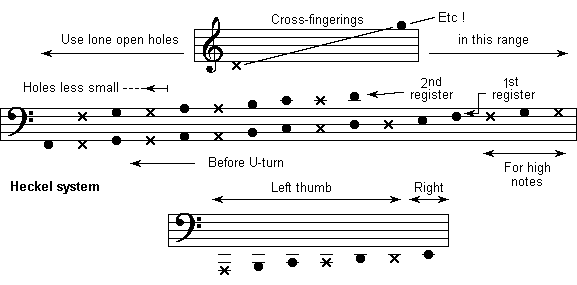

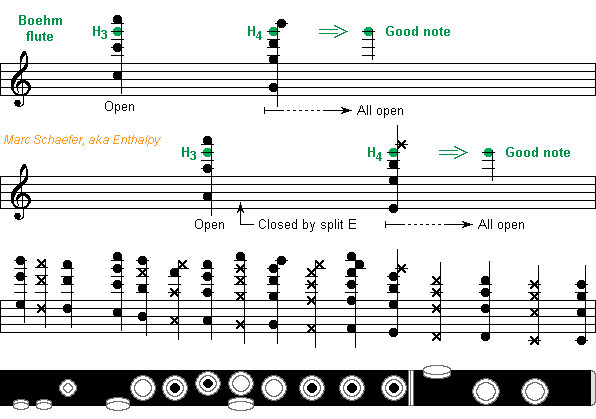

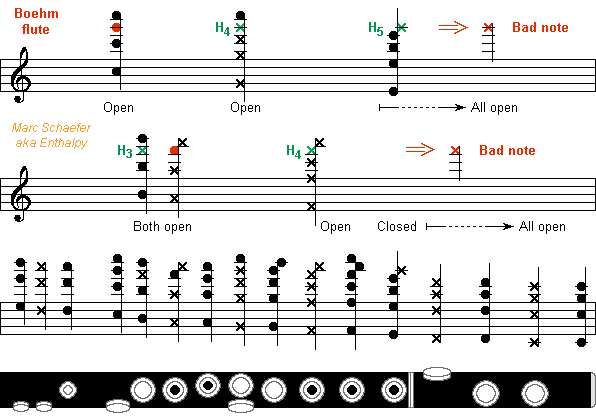

It is well known, but not by every musician: several notes on the Boehm flute use an imperfect combination of open holes which hamper the emission or the intonation. Here are two examples of good notes, high E and high G. Following Obukhov where one note marked with a × is half a tone higher, the lowest line shows what notes a given tonehole can emit. On the flute they are nearly harmonic and have a pressure node at this tonehole's location, or more accurately, little below. High E and G open two properly located toneholes, which could each emit the desired note, and this reinforces the air column's resonance. It also spoils the unwanted modes of both individual toneholes, so that only the desired note resonates well. 3 and 4 being relatively prime in these examples, the next good resonance would be an octave higher, on modes 6 and 8. If a flute has no split E mechanism, the tonehole emitting G# remains open for high E and makes it logically less stable. Due to mechanical couplings meant for other notes on the Boehm flute, several notes use imperfect combinations of open holes. The high F# leaves open the tonehole for Bb and harmonics, half a note lower than the correct tonehole for B, making the high F# less stable than its neighbour F and G. The high G# opens the tonehole for C and harmonics, instead of the lacking tonehole for C#, so the high G# uses to be badly low. On most instruments, the high G# can't be fully corrected by the musician, who gets accustomed to play it out of tune. This is what flutists should test at an instrument. Play legato repeatedly the high F-F#-G-F#- as pianissimo as possible, check when the F# disappears: it tells how difficult the instrument is on demanding détaché, fast, piano sequences. Play legato repeatedly the high G-G#-A-G#- without any lip correction, or simple intervals like Eb-Ab, and check the intonation: usually very poor. Play legato repeatedly the medium and high C-C#-D-C#- without any lip correction, and check the intonation by the index tonehole misused by the Boehm flute for C#. And of course, try the lowest notes forte and the highest ones pianissimo, but this doesn't result from mere hole combinations. The explanation above is only a first analysis. Even the flute's huge toneholes are inductive hence placed too high. Opening sereval holes for the third octave shifts the notes higher. Makers of Boehm flutes adjust the toneholes' size and position ("scale") to improve the imperfections. But as each hole influences several notes, the adjustment is nontrivial and needs compromises. About every flute today uses the (1972) Cooper scale, improved by Bennett. Its high A, despite opening the ill-placed tonehole for G#, is stable and in tune. Its high F# is in tune but imperfectly stable, its high G# is badly low, and both C# depend on each model. The New Cooper Scale is allegedly better. I tried at a Paris repair shop the single only flute perfectly in tune because the expert had shifted the toneholes himself, but the low notes were weak. I tried around 2003 a new wooden flute by Yamaha with the "Type 4 scale" or its predecessor, which offers the strongest low notes ever and whose intonation is excellent, but soloist will supposedly dislike its soft tone. So while better scales than Cooper-Bennett exist for the Boehm flute (wake up!), this tinkering is by nature limited and implies trade-offs. Further gains can result from small or big changes to the Boehm system. Cooper had continued to experiment. For instance, he added at the thumb the missing C# tonehole. I ignore what mechanical couplings he foresaw and haven't tried such an instrument. By making the eight high toneholes independent, my fingerings never open the wrong one, and hopefully avoid all trade-offs. The scale adjustments must be done again from scratch. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Electric helicopter

Hi Sensei and all, oxygen comes from the air, yes. This is what makes hydrogen much lighter than kerosene. Agreed with 51g/s oxygen needing some 0.2m3/s air. But this is little, especially in an aircraft where air moves already. Take 20m/s under the rotors, it's a D=0.1m intake. An other logic is that the helicopter uses car fuel cells, which get enough air when used in a car. The helicopter has 6 cells instead of 1, and it suffices that each cell has an intake as big as on a car.