Everything posted by Eise

-

Did the bing bang actually happen?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Big_Bang#Observational_evidence

-

Could all mass be grounded by mass ?

I don't know what the original language was, but I assume it was German. Here I found this German version: And that is 'parts'. But I am not sure how reliable that website is. But googling the whole sentence, I find a few other citations, but no other with the complete text, except other English translations. The few I looked at all say 'parts'.

-

ChatGPT logic

Yep. A version of ELIZA was implemented in Emacs: Wikipedia

-

ChatGPT logic

Thanks for the reference! I must assume now that @bangstrom is a pre-alpha release of ChatGPT, trained with the contents of the internet until about 1935 . However, I think that the program has some access to the internet. E.g. it knows that Zeilinger got the Nobel price. I assume it uses a Google API, picking some information that seems to fit to the contents of its pre-1935 training program, and somehow seems to support its position. It is clearly mimicking intelligence, but it is way behind its present Big Brother, ChatGPT.

-

crowded quantum information

In which article of Bell? You made the citation, you should know. I did not find it, until now. You don't? If there were local hidden variables, there is no need for any signal. The electrons or photons would carry an attribute that would locally determine the measurement outcomes. SR is one of the best proven theories in physics, and essential in QFT, Electro-Magnetism, E = mc^2, and a hell of a lot more. It is intrinsic to the metric of spacetime. BS: From Wikipedia. Yes, no one is denying entanglement, but it only exists 'in the quantum world', and in QM there is no need for an FTL signal. Just a correlation that is greater than classically possible. Trying to understand this correlation classically, one would need an FTL signal. Ah, nearly forgot that you have reading problems. From the same article: Except the distance it is the same. Also in bound states the spin states are not determined, until measured, and they are just as well anti-correlated. Good. So now where do you still have problems with Markus' explanation? It must be somewhere, because it is clear his conclusion is that there is no FTL signal.

-

crowded quantum information

John Bell? Less so: that is from the EPR-article. And you said somewhere 'EPR is invalidated' (whatever that means...) But now it supports your viewpoint? Wow. If you read the rest of the statement John Bell was listing in the quote the sort of things he considered “hidden variables’ in the EPR article and the hidden variables were what Aspect and Clauser ruled out as invalid fifty years ago. Seems you did not understand my remark. Your citation is from the original article by Einstein, Podolsky and Rosen. (That you claim is 'invalidated', whatever that means). It is not mentioned in Bell's 'Bertlmann's Socks'. And I fully agree that hidden local variables are ruled out. Right. Except that it was E, P and R's comment, not Bell's. But the absence of local hidden variables does not mean that the only alternative is an FTL signal. An FTL signal: does not appear in the QM that explains the correlation between the measurements, so you cannot build your argument for an FTL signal on QM. Markus explained this clearly in his post on page 22 is forbidden by SR in principle cannot physically exist because for observers in different inertial frames the direction of the signal can differ. That means they differ about the direction of the causal relationship between the measurements. But in SR all inertial observers agree in the direction of causal relationships. Really? You said: Italics by me. So the timing of the classical signal and the measurement are essential. Ask Zeilinger to do his 'teleportation' without classical signal. If you say it is not essential, then you can do without. (But why should the timing be so important...?) Nope. Complete false picture of entanglement. The particles are anti-correlated per definition of what entanglement is. We know the particles are entangled, so that they are anti-correlated. That is exactly what entanglement means: the particles are (anti-)correlated no measurement was done on the particles yet We just don't know what the measurements will result to, but if we have a pure singlet state, and we know the spin is up in one direction, then the other particle, measured in the same direction, will be down. But this is based on the correlation between the particles. And in QM this correlation is stronger than we can understand classically. So if you think classically, where such entanglement does not exist, we must conclude that there is a FTL signal. So your way of thinking is already more than 90 years outdated. Exactly the opposite: the singlet state is the fully entangled state. Exactly as Markus described. Please give an exact citation where Markus said that. You even agree: Now what is this 'hidden variable ruled out by the Bell test'? That the particles are entangled? Or is a hidden variable an attribute of the particles from the beginning, that determine which particle will show which spin? 🤣

-

crowded quantum information

Which statement you mean? Please give this 'rest of the statement' and a link to the article where it comes from. Does teleportation work when you omit this preparation? If not, then the classical signal is essential. Nope. You must read it as 'quantum entanglement can only be understood by using quantum mechanics'. There is no FTL signal in the quantum mechanical explanation. QM entanglement cannot be simulated with classical means, unless you allow for FTL communication. And you evaded my first point. Here it is again for you: Oh man, trying not to loose your face, you now even have lost sight of what entanglement is. We know that the particles are entangled from the beginning, because they are produced entangled. Do you suggest to show entanglement is real by using particles that are not entangled from the beginning? That is the crux of the 'singlet state': we know the wave function of both particles together, but not of the individual particles. That means we know the outcomes of the measurements must be (anti-)correlated.

-

Aliens and FBI

From your link https://kiisfm.iheart.com/content/2022-05-09-best-photograph-of-a-ufo-ever-taken-has-experts-stumped/: I have read similar comments on a lot of UFO photographs. So I am all in for TheVat's '3rd alternative':

-

crowded quantum information

Oh man, trying not to loose your face, you now even have lost sight of what entanglement is. We know that the particles are entangled from the beginning, because they are produced entangled. Do you suggest to show entanglement is real by using particles that are not entangled from the beginning? That is the crux of the 'singlet state': we know the wave function of both particles together, but not of the individual particles. That means we know the outcomes of the measurements must be (anti-)correlated. John Bell? Less so: that is from the EPR-article. And you said somewhere 'EPR is invalidated' (whatever that means...) But now it supports your viewpoint? Wow. The 'only purpose'? That 'purpose' is central for quantum teleportation to succeed. The classical signal is necessary for teleportation. But I fully agree with Markus that when discussing entanglement in itself, you should not use more difficult setups that make use of entanglement. If you think classically, yes. But that is exactly what the Bell theorem says: the only way one could simulate entanglement with classical means would need an immediate interaction between the entangled particles. As you think classically, you think it needs an FTL signal. Your arguments become worse and worse. Oh my, page 25...

-

crowded quantum information

Oh, c'mon. c is the lightspeed through vacuum, not relative to vacuum. Yep, that is what characterises entanglement. The directions of the spins are anti-correlated, meaning that we know from the beginning that if we 'add the spins' (when measured in the same direction), we will get zero. Just as a remark, in some experiments, with photons e.g. the particles are correlated. But I'll go with your anti-correlated example, no prob. Nope. The 'hidden variables' ruled out by the Bell test are properties of the particles that determine in advance what spins will be measured. On one side, exactly, but you look with 'classical eyes' on entanglement. That is your problem. On the other side, no: besides the entangle particles needed in quantum teleportation, there is also a classical signal needed. You know that very well.

-

Dropping Like Flies Worldwide

In the US there are many more Republicans dropping dead than Democrats. Just guess why... Two hints: Which group was more vaccinated? Which group did take social distancing and masks more serious? The risks of Covid vaccination are negligible compared to having Covid. From More Republicans Died Than Democrats after COVID-19 Vaccines Came Out

-

A wormhole simulation on some kind of a quantum computer

Peter Woit shows the emperor has no clothes: From 'Not even wrong'. And a citation in Peter Woit's comment from Brown and Susskind:

-

Power of One

No, I said: a^3 = (a^4)/a There are several other ways to see it, but they all are variations of the same theme: a^4 = a x a x a x a a^3 = a^4/a = (a x a x a x a)/a = a x a x a a^2 = a^3/a = (a x a x a)/a = a x a a^1 = a^2/a = (a x a)/a = a a^0 = a^1/a = a/a = 1 In short, the obvious rule is that with division of powers, you subtract the powers: (a^n)/a^m=a^(n - m). So when n = m: (a^n)/(a^n) = a^(n - n) = a^0. But dividing two equal numbers always gives 1. (Except 0^0, which can not be defined.)

- Power of One

-

Zero Power

One simple way to see it: a^3 = (a^4)/a a^2 = (a^3)/a a^1 = (a^2)/a = a a^0 = (a^1)/a = a/a = 1 Does that make sense?

-

crowded quantum information

The second postulate is that the speed of light is the same for all observers. (And not that c is the limiting speed of material objects.) As said, 'my light cone' was also of Joigus. AFAIU Joigus' intention with the latest, was to show that your remarks about light cones were much too vague (as usual): they also fit these funny space-time diagrams. So you are just reinterpreting a piece of science history. I am sure Ole Rømer hypothesized that the anomaly in the orbital times of Jupiter moons was caused by a signal delay, i.e. that the light signals do have some measurable speed. So this is no argument at all. The units, yes. But light has a fixed speed in vacuum, independent on which units we use, be it inches, cm, meters, seconds, minutes, hours. Yep, this anti-correlation is given, as we are talking about entangled particles. What would entangled particles be without correlation? So the correlation 'an sich' is not a hidden variable at all. The Bell experiments prove that the correlation is stronger than can understood classically. And you are arguing classically all the time, so no wonder you keep hammering on the idea that there should be a signal, interaction or whatever. Where did Markus say that the direction of the spins are fixed? Nope. They even had to delay the entangled photon, so that the classical signal would be at the other side first. The correlation between the entangled photons is instantly, yes, but that is just an attribute of any form of correlation, like the left and right shoe example. quantum teleportation as a whole is not instantly.

-

crowded quantum information

Eh? Joigus did it: It seems you really do not understand EM either. Just take the historical lesson: Maxwell discovered the laws of EM, based on the experimental results of Faraday, and his ideas of electric and magnetic fields. Maxwell discovered that his equations implied that EM waves should be possible, because he could derive a wave equation from them. According to plain old classical wave mechanics, he showed that the speed of the waves should be sqrt(1/(mu_naught * epsilon_naught)). As this fitted very well to the known speed of light, he concluded that light is an EM wave. And now you say that c is not so much light speed????? Oh my. I also want to mention, that you obviously simply do not understand, or evade all explanations given. On one side, you said you fully agreed with Markus' first explanation (but where for me it was obvious that this could not be, he clearly explained why you were wrong). But then, Markus showed you made the same errors all over again. So you did not understand one word of what he was arguing. Please, learn real physics.

-

crowded quantum information

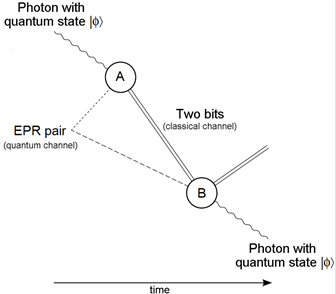

And I explained that nobody was even saying this. So you were beating a dead horse. So let's try to explain it once again. As a starting point we take a Bell experiment, that closes the communication loophole. This means: the measurements cannot influence each other with a light signal, or any slower signal the decision which spin direction will be measured is taken after the particles left the entanglement source So there can't be any causal connection between measurement device A, B, and the entanglement source. Said otherwise, no communication is possible between these 3 components. To make the example as simple as possible we also assume that detectors and entanglement source do not move relative to each other, and the entanglement source is exactly in the middle, so the measurements are exactly at the same time in the rest frame of the experiment. Are you with me so far? Maybe Joigus' drawing helps: Just take Alice and Bob as other names for the detectors. So now we ask ourselves what Carla and Daniel will see. Well, it is in the drawing: in Carla's frame of reference the measurement at Bob's side is first, for Daniel's FoR it was Alice's side. It is just a question of perspective, not of changing anything with the experiment of course. Got that too? Now according SR observers can disagree on the timely order of events, when these events are space-like separated. But that is exactly what the closing of the communication loophole means. But SR also states that Carla and Daniel should at least agree on the physical process. But they don't: according to Carla, Bob's measurement determined the outcome of Alice's according to Daniel, Alice's measurement determined the outcome of Bob's But these cannot both be true. So the conclusion is that there is no 'determination relation' between the measurements. So no signal, FTL or not. For Alice and Bob of course nothing changes. In their FoR the measurements are simultaneous, just as before. So Carla or Daniel have no influence at all on the experiment. But they should agree at least on the physics.

-

crowded quantum information

Seems you have wax in your ears: Nobody claims that observers that are in other inertial frames of reference affect the experiment. There you are right, for one time. To understand entanglement, one must understand QM. But as said, SR is a 'filter' for possible explanations. If an explanation is in conflict with SR, then it is wrong. Yes, that is what I said. (No, it wasn't, but I let that be.) Then did you read it well? Or didn't you understand it (again)?

-

crowded quantum information

Now it would be interesting to know if you agree with Markus' descriptions. 'Unrelated'? You simply do not see what the relation is. One could call SR a 'meta-theory': it describes how space and time transform when seen by different inertial observers. As we all observe physical phenomena in space and time, all fundamental laws of physics must pass the test if they are Lorentz invariant. If they are not, then they are not correct. An FTL signal does not pass the test, so an entanglement explanation that contains an FTL signal cannot work. That is the whole argument in a nutshell. Even QM must 'obey' special relativity, which it does, as QFT.

-

crowded quantum information

And of course a +1 for Markus. At least I understand it a little more clearly now.

-

crowded quantum information

That goes back to the old example where lightning strikes both ends a train simultaneously on both ends relative to an observer in the center. Oh my. In the entanglement situation we are discussing that different inertial observers, in your interpretation where there is a FTL signal, must see one signal (between the measurements) going into opposite directions, but taking the same trajectory. And now you come with an example with two signals, taking two different trajectories, one of the front of the train to the middle, the other from rear to the middle. And this has to do nothing with SR. SR is not about observers being at different locations. That can be handled just as well with Newtonian mechanics. Just take the signal velocity in account, and you are done. SR however is about the different observations by observers in different inertial frames of reference, i.e. observers that move (fast) relatively to each other. Do you know the difference between spacial distant events, and space-like separated events in SR at all? I thought so. Case closed. Ah. It only violates one of the two groundstones* of SR, without which SR would be thoroughly false. At the same time SR is essential to our understanding of QFT, it is the basis even of our classical understanding of electro-magnetism, it is practically essential for GPS and particle accelerators, it explains the colour of gold and the liquidness of mercury, etc, but yeah, the invariance of light speed is just a provisional conjecture. You have no idea how SR is one of the roots of our understanding of the physical world. Every fundamental law of nature must pass the criterion that it is Lorentz invariant, i.e. does not lead to inconsistencies when we apply SR. * BTW the second postulate is not that nothing can go faster than light, it says that the speed of light is invariant. That no material object can reach the speed of light is a conclusion of SR. He, 22 already! Do not eat too much popcorn...

-

crowded quantum information

Nope. You said: For which I wanted an explanation. Then you said: And then I asked an example of information transfer, or a signal, that works without a transfer of energy and/or matter. So maybe I was a bit confusing, but I want two examples: One of "Different observers seeing signals going into different directions" and how this is "a well understood phenomenon of SR". Information transfer or signal, without any energy or matter involved. And both not using entanglement, because that would mean you are using your conclusion about entanglement as argument, with other words you would "beg the question". And I am still waiting for a reaction on my posting:

-

crowded quantum information

Nope. An observer with a constant velocity compared to a defined inertial frame will observe distances, durations etc differently from an observer in that defined inertial frame. What is true is that when we have an inertial frame of reference, and an observer is moving with constant velocity relative to that inertial frame, then that observer is also in an inertial frame. But it is another one.

-

crowded quantum information

So you mean the entanglement source and the detectors are in same inertial reference frame, in other words, they are at rest relative to each other? Then say so. Next step: is this a preferred frame of reference? A preferred frame of reference in this context would mean that only in this frame correct conclusions about what physically is happening can be drawn. Next step: according to SR there are no preferred inertial frames of reference. Still, all observers, whatever their speed and direction, agree on the physics about what is going on. (However they can differ on distances, durations, timely order of events, simultaneity etc.) That is against 1., so 1. does not apply: the inertial frame of the experiment is not a preferred frame of reference. Next step: if there is a physical signal from one measurement to the other, all inertial observers should agree on this signal, especially its direction. Next step: for some observers Alice's measurement was first (e.g. Daniel in Joigus' drawing), for others Bob's measurement was first (Carla). Next step: Daniel and Carla do not agree on the direction of a hypothesised signal. But as they, according to SR, should agree on the physics of the situation (in this case which measurement determines the other), there can be no signal. As you see, there is no influence whatever from the different observers. Italics: Nope. Every observer observes the measurements, but they do not agree with each other which was first. So there is no objective first. Just to be sure: that is only true when the measurements are space-like separated, in the SR meaning of that concept. Not just space separated. Which you are using in your next argument: Oh my! In SR we talk about inertial frames of reference, not about the position of observers in space! It is 'easy-peasy' for Alice, if she knows the distance to Bob's detector, to conclude that his measurement was at the same time as her measurement. If detectors and entanglement source are in the same inertial frame of reference, Alice and Bob can agree on which measurement was first (or if they were simultaneous). Obfuscation from your side again: you have changed the meaning of 'reference frame'. Or you have a total misunderstanding of SR. Or both. Nope. I say that for space-like separated events there is no objective order of events. And just observing does not change anything. Do you really think we are saying that Carla and Daniel change the 'objective' order events, and that in different directions?