Everything posted by Markus Hanke

-

Is "positionary-temporal" uncertainty built into spacetime?

No, but I think you have picked up on that yourself already. The crucial feature of Minkowski spacetime is found in how it defines the separation between points. You might remember from your school days the Pythagorean theorem - if you have a pair of points in some Euclidean space, the squared separation between them is the sum of squares of coordinate differences: \[(\Delta s)^{2} =( \Delta x)^{2} +( \Delta y)^{2} +( \Delta z)^{2}\] In Minkowski spacetime, you have one additional dimension, being time - so the squared separation will involve four coordinates. However, unlike in Euclidean space, Minkowski spacetime does not simply add them; instead it ensures that time and space have opposite signs in the separation formula, like so: \[(\Delta s)^{2} =( \Delta t)^{2} - ( \Delta x)^{2} -( \Delta y)^{2} -( \Delta z)^{2}\] So the squared difference isn’t just the sum of (squared) spatial separations, but the difference between (squared) separation of time and space: (total separation)^2 = (separation in time)^2 - (separation in space)^2 Note that the choice of signs is arbitrary - I could have made time negative and space positive, without affecting the result. This is an example of hyperbolic geometry (as opposed to Euclidean geometry). What does this do physically? Well, having a difference rather than a sum enables you to make simultaneous changes to the space part and the time part in equal but opposite measure, without affecting the overall separation in any way. So you can trade a decrease in space for an increase in time (or vice versa), and still end up with the same overall separation. And that’s exactly what happens in Special Relativity - for example, if you are looking at a clock passing you by at relativistic speeds, you’ll find that the clock is time-dilated (meaning it takes longer for the clock’s hands to move, from your point of reference), while at the same time the clock itself will be length-contracted in its direction of motion, so its size becomes shorter (again, from your point of reference). So in this scenario, and from your point of reference, “space is traded for time”, in a manner of speaking. This happens in equal but opposite measures - the decrease in size is by the same factor as is the increase in time - which is why the ratio between them remains the same always, which physically means that the speed of light is always the same in any inertial frame. This is is purely a consequence of the hyperbolic geometry of Minkowski spacetime. A simple change in signs makes all the difference! The above is very simplified and not especially rigorous, but hopefully you get the central idea.

-

What is gamma factor of object, which is falling into black hole?

Yes, of course. It depends on the effect. In the simplest cases, they just add - for example, the total difference in tick rates between a clock on earth and a clock in an orbiting satellite will just be the sum of gravitational time dilation and kinematic time dilation between these frames. Yes. Personally I associate the gamma factor with inertial frames in Minkowski spacetime, since gamma arises from Lorentz transformations. I think in the interest of clarity and consistency it is best to avoid this terminology when working in curved spacetimes, and just refer to the specific quantity in question instead. For example, in the OP’s scenario it would be best to speak about time dilation, rather than the gamma factor, simply to avoid unnecessary confusion. There’s also the danger that someone might naively take the gamma factor and apply it to quantities that ‘behave’ differently in the presence of gravity - take for example the OP’s scenario, but use the observed length of the falling object as the quantity in question, rather than time dilation. The result won’t be correct, because in an inhomogeneous gravitational field you have extra tidal effects that don’t exist in Minkowski spacetime. To be fair, you could again separate the various effects, as you suggested - but I think you can see the potential confusion a naive application of gamma to frames in curved spacetimes might cause.

-

What is gamma factor of object, which is falling into black hole?

The gamma factor is used to characterise the relationship between inertial frames in flat spacetime, ie between frames that are related via Lorentz transformations. When you have a test particle freely falling into a black hole, it will trace out a world line in a spacetime that is not flat - you can still choose another far-away frame as reference, and both of these will be locally inertial, but spacetime between them isn’t flat, so these frames are not related by simple Lorentz transformations. Hence, asking about what the gamma factor between these frames will be is meaningless - it is only defined for frames that are related via Lorentz transforms.

-

There are Physical Concepts that is Left Up To Magic

In classical vacuum, you have at a minimum two fields defined at each point - the metric tensor field (gravity), and the electromagnetic field. Both of these are rank-2 tensors, so there’s lots more going on than a single number. Note that even at points where the EM field strength is zero, you can still have physical effects resulting from the presence of its underlying potentials (eg Aharanov-Bohm effect). In quantum vacuum, in addition to the above, you’ll also have the full menagerie of all the various quantum fields associated with the standard model, even in the absence of any particles. This matters, because, unlike in the classical case, the energy of the vacuum ground state of these fields is not zero, and you can get various physical effects resulting from this. This is true only for fermions, but not for bosons. No. What matters are the physical effects a field has; again, the Aharanov-Bohm effect is a good example. The laws of physics do not depend on the choice of reference frame. You can change your coordinate system at any time without affecting any laws (general covariance). Note that this also does not change the number of coordinates required to uniquely identify a point.

-

Exponents - Why is 2 to the power of 1 not 4?

That’s not a very good definition, IMHO - especially since the exponent can be any number, even a negative one, a fraction, an irrational one, or a complex number. Let’s stick to simple, natural numbers like 1,2,3,... for now. Exponentiation is then a short-hand notation for a multiplicative series starting at 1, followed by as many multiplications with the base number as indicated in the exponent: 1 x ... x ... x ... and so on Thus: 2^0 means you start at 1, followed by no further multiplications. Thus 2^0=1. 2^1 means you start at 1, followed by exactly one multiplication by 2. Thus 2^1=1x2=2. 2^2 means you start at 1, followed by two consecutive multiplications by 2. Thus 2^2=1x2x2=4. 2^3 means you start at 1, followed by three consecutive multiplications by 2. Thus 2^2=1x2x2x2=8. And so on. Does this make sense now?

-

There are Physical Concepts that is Left Up To Magic

Pick a random point in - say - your living room. At that point, you can define a value for air temperature - a scalar. At the same time, you can define a value for air pressure at that same point - another scalar. You can further define a quantity to measure air flow there - a vector, since it has magnitude and direction. Or you can define the stress within the air medium at that point - a tensor. Or perhaps you could look at the electromagnetic field there - a differential 2-form. And so on. So as you can see, not only can a single point ‘take’ more than one field value at a time (each of which reflects a different physical quantity), the fields themselves can consist of many different objects, not just simple scalars. They can even take more abstract objects that don’t have numerical components at all, such as operators. This is all rigorously defined, and works precisely as it should - the very computer you are using right now is built upon these principles.

-

Do we really need complex numbers?

I think a far more interesting operation appears when one uses complex numbers as exponents - suddenly we are now dealing with rotations and scalings, which is a much richer structure than real exponents can yield. This being linear transformations, it’s not surprising that there is a close connections to certain types of matrices. Either way, the results I linked to seem to show unambiguously that - for whatever reason - complex numbers are indispensable for QM.

-

Reverse space and matter!

It doesn’t - all known physics obeys locality. What happens is rather that changes in one system that affect another are mediated by various kinds of fields. For example, the presence of electric charges implies the presence of an accompanying electromagnetic field, which extends throughout spacetime and thus affects other (distant) electric charges. This has all been worked out in detail - electromagnetism, strong and weak interactions are well described by quantum field theory, whereas gravity is described by General Relativity (which is also a field theory, but of a different type). There are no ‘actions at a distance’, in the sense of non-local effects.

-

Do we really need complex numbers?

This is true in classical physics, but as it turns out it is not true in quantum mechanics. You can construct a class of experiments where real-valued QM (replace complex numbers by pairs of real ones) makes predictions that are different from complex-valued QM, thereby opening up a way to test this experimentally. Turns out, complex Hilbert spaces are an essential feature of any QM formalism that describes the world accurately (within that domain): https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.10873

-

I could not reach Scienceforums for 3 days

No - I’m currently in Australia, and had the same problem here too.

-

Is it possible to write the Dirac equation without spinors?

Bispinors are covariant objects, as are the gamma matrices, so the Dirac equation, when written using Dirac notation, has the same form in all reference frames - just like a tensor equation would.

-

Is it possible to write the Dirac equation without spinors?

Yes, it’s possible to do this, since both bispinors and rank-n tensors are possible representations of the Lorentz group. Essentially, you replace the bispinor by an ordinary 4-vector, and replace the gamma matrices by rank-3 tensors. So what you’re really doing is shift some of the transformation properties concerning rotations - encoded in the bispinor - into the gamma matrices themselves. The result can be shown to be physically equivalent to the ordinary Dirac bispinor formalism. For example: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/1898363_Dirac_Equation_Representation_Independence_and_Tensor_Transformation But why would you want to do this, I wonder? Bispinors already transform in the same way as tensors, so they are tensor-like objects - unsurprisingly, since both objects are representations of the Lorentz group.

-

Hypothesis about the formation of particles from fields

No it’s not. It’s the simplest possible wave equation for a relativistic scalar field without spin. There’s nothing controversial about it. It’s not an arbitrary assumption - the Klein-Gordon equation is simply the Euler-Lagrange equation corresponding to the simplest possible Lagrangian for a scalar field. Of course - that’s because the equation is Lorentz invariant, so space and time need to be treated on equal footing. This follows directly from the Lagrangian.

-

What is the difference between a magnetic and an electromagnetic field?

Well, a magnetic field is a particular aspect of the more general electromagnetic field - simply speaking, its defining characteristic is that magnetic field lines do not end anywhere, ie they either form closed loops or extend to infinity. In contrast, the field lines of the electric field begin or end at electric charges, but never form closed loops. Both the electric and the magnetic field are aspects of the same underlying entity, which is the electromagnetic field. All observers agree on what the EM field is, but they each see a different mix of electric and magnetic fields, depending on their state of motion with respect to the sources (electric charges).

-

State of "matter" of a singularity

That’s right. This doesn’t mean simultaneity (which is a meaningless concept since there’s no valid frame for photons). It means that, if you choose arc length as your parametrisation on the geodesic, then the overall spacetime interval between two neighbouring points on that curve is zero. IOW, the time and space parts within the line element are of equal magnitude. I think I know what you mean, and it makes perfect sense. The question then becomes what the chart (or: the choice of surface - same thing?) itself physically represents. If you schematically equate a choice of charts with a choice of scale, you’d recover our usual hierarchies of QFT-QM-Classic. But that’s not enough, we’d need to know the precise physical meaning. The reminds me suspiciously of the concept of emergence, tbh.

-

Gravitation fundamental fields

That’s not true. General Relativity - which is the best model of gravity we currently have - is a purely local constraint on the metric of spacetime. The influence of distant sources enters only via boundary conditions. In order to capture all real-world degrees of freedom of gravity, you need at least a rank-2 tensor field. Scalar and vector fields aren’t enough. The div, grad and curl operators are only defined in three dimensions, but our universe is manifestly 4-dimensional. These equations are also not covariant, so you need to specify what frame you are working in. It is possible to formulate gravity in the way you suggest (this is called gravitoelectromagnetism), but this only works as an approximation in the weak field limit. A full description of gravity requires GR.

-

State of "matter" of a singularity

Sorry everyone for not replying to your comments - my focus is currently on things related to my real-life vocation, so I’m not online much. In whose frame? What do you have in mind when you say “surface”? As in, a 3D surface in spacetime? I remember that MTW takes a very different approach to justifying the form of the EFE - that is, via topological principles, specifically the fact that the boundary of a boundary is zero, which leads to the automatic conservation of certain quantities. I will have to review my notes on this first though, as I’ve grown a bit hazy on the details. This may be relevant here though.

-

State of "matter" of a singularity

I’m not sure we differ on this - I completely agree that you can choose whatever type of diagram in whatever coordinate system is most useful for the particular problem at hand. There’s no right or wrong way, only usefulness and its opposite. That’s precisely the beauty of GR - the physics do not depend in any way on how you label and depict events in your spacetime. Labels don’t have physical significance, only the relationships between them do. There are just two points that need to be borne in mind: 1. A choice of coordinate system generally (not always) corresponds to choosing a particular observer, so it will reflect how that specific observer evaluates the situation using his own local clocks and rulers. This is very important, since notions of space and time are purely local, so different observers will differ on these without creating any physical paradoxes. They’re bookkeeping devices - like accountants using different currencies may come up with different-looking books for the same company. In particular, Schwarzschild coordinates (irrespective of where you place the origin) physically correspond to a far-away observer at rest, and will thus reflect the far-away stationary notion of clocks and rulers. For obvious reasons, if you plot null geodesics on a chart using these coordinates, they will never reach or intersect the horizon on that diagram (!!!). I’m highlighting and exclamation-marking this to point out that such a diagram is observer-specific and reflects only what this particular observer calculates using his own local clocks and rulers. 2. There is no rest frame associated with photons, so, unlike is the case for time-like geodesics, you cannot parametrise photon geodesics by arc length (=proper time), since ds=0 by definition. Instead you can use an affine parameter of your own choosing. I completely agree, especially since we already know that our usual paradigms don’t work for this. In particular, I suspect that any notions of smooth and regular space, time, spacetime with well-defined causal structures, and fields on spacetime will become meaningless in the realm of quantum gravity. Physics there will deal with dynamical quantities that are very different from those of ordinary classical physics, or even those of quantum physics, which will likely change the way we think about reality in very fundamental ways. I hope I will get to see it in my lifetime, but it’s possible that we are still a long way from such a model. There’s no way to tell, really.

-

State of "matter" of a singularity

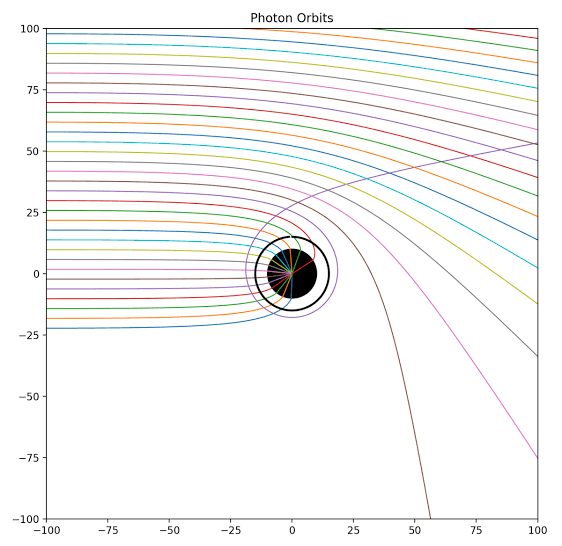

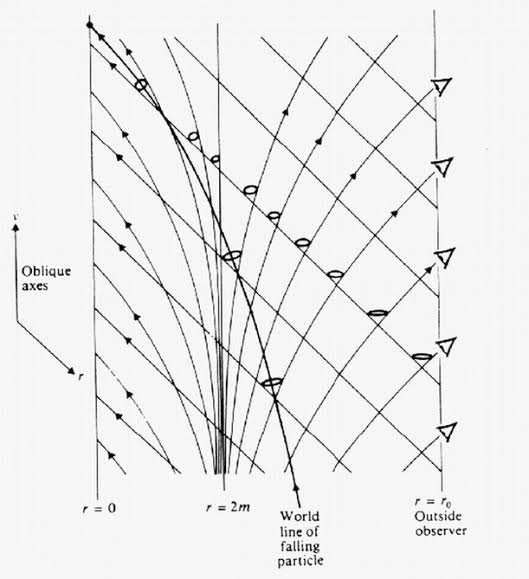

You’re absolutely right, it doesn’t make a lot of sense - but I think in the absence of a quantum gravity model, this semi-classical approach is pretty much the best we can do. I do find it encouraging, however, that it is in fact possible to have both GR and QFT be valid simultaneously on the horizon while still producing sensible results. To me this indicates that our quest for quantum gravity hopefully won’t be in vain. Yes, of course. Null geodesics are geodesics in spacetime, just like all geodesics are. You cannot have dynamics of any kind on a single hypersurface of constant time - the wavefront will just appear as a static circle there. Only if you combine many such surfaces into a stack, does the cone appear. This seems to me so basic and obvious that it never occurred to me that it needs explicit mentioning. The light cone diagram has space and time axis, after all. But I concede it could be my fault - I’ve been doing GR for a long time, so I tend to take some things for granted that mightn’t be immediately obvious to others. One becomes a bit complacent. I suspect the confusion might be due to my earlier example of ripples on a pond? If so, I apologise - it was meant only as an analogy, and perhaps I didn’t explain myself properly at the time, thereby causing confusion. The light cone is a valid representation of the propagation of light waves away from some source (at the origin of the diagram), where the cone itself would be the set of all possible null geodesics. However, as it is usually drawn, the diagram only works for flat Minkowski spacetime. For curved spacetime, these diagrams only make sense locally, in a small and thus nearly flat region. If you need to depict light propagation through larger regions, then light cone diagrams are wholly unsuitable; you’d instead choose specific boundary conditions that are of interest, and draw out the worldlines of individual photons - which would just be a single trajectory in spacetime. For example: This is just a random example of how to plot null geodesics around a Schwarzschild BH. If you want to still use light cone, you have to draw several of those in different places, to visualise the metric (=causal structure) of spacetime. For example:

-

State of "matter" of a singularity

I’m afraid I don’t quite follow you - you cannot derive the entropy of a BH in any way from either the Einstein equations or QFT alone; you need to assume the validity of both GR and QFT at the horizon. The existence of entropy (and Hawking radiation) is a consistency condition that must hold for these two to play nice together. So BH entropy is fundamentally a semi-classical result. Within GR alone, the concept of entropy is meaningless. I haven’t been online much lately, so haven’t been following along with this thread. I’ll try to explain it again: The horizontal plane represents space at time t=0, being the instant of emission - we suppress one dimension here, to be able to draw the diagram at all. The vertical axis is time. Saying that the light propagates on the plane within that diagram isn’t really correct, because that’s a snapshot of space at a single instant in time. So there are of course no dynamics on that plane itself. To see how light moves, you can draw another plane further up at, say, t=1 - that’s also a snapshot of space at a single instant, but the wavefront will now be at a different spatial position, some distance away in all directions. You can keep doing this, and draw a whole stack of such planes, which gives you a sense of how the wavefront expands away from the emitter over time. The continuum limit of this plot will be the cone itself of course. So, to be precise, the position of the wavefront at a given time t is at the intersection of the light cone with the hypersurface of simultaneity corresponding to t; meaning it would appear as a circle on a plane that is parallel to the base plane for t=0. For all intents and purposes the light cone itself is thus a schematic depiction of how the wavefront would propagate through space over a period of time, with one spatial dimension omitted. Bear in mind here though - and this is important - that all angles and distances on this diagram explicitly depend on the metric. In curved spacetimes, then, a light cone is a purely local object, and light cones at different events will be tilted and distorted with respect to each other.

-

A geometric model that has a maximum speed

Constant means it has the same numerical value everywhere, whereas invariant means that it doesn’t change when going into another reference frame. The speed of light depends on the medium, so it’s value is always invariant, but constant only within the same medium. I don’t know what you mean by this...? It’s obviously not the same everywhere, since it depends on the distribution of sources. \[c=\frac{1}{\sqrt{\mu_{0} \epsilon_{0}}}\]

-

State of "matter" of a singularity

You’re still missing the point here - the light cone is not meant as a way to visualise trajectories of anything, which is why the question is somewhat misplaced. In some sense it does indeed show how light travels on a time vs distance plot, but that’s not its purpose. Its purpose is to show regions of causality relative to a given event. It is called “light cone” only because that surface represents the maximum distance from the event any signal could have travelled at a given point in time, which of course relates to the speed of light. The way it’s meant to be used is that you draw in some other event, using the given coordinate axis - and then see immediately whether these events are causally connected, or not. IOW, the light cone is a way to visualise those regions (!) where the (flat) spacetime interval between events is positive, negative, or zero, as a function of coordinates. I don’t think that’s very surprising, actually. Taking h->0 on the boundary physically just means that spacetime on the bulk is taken to be smooth and continuous; so you can swap any two events without changing anything about the BH. So of course the entropy will diverge. Having h be a finite value on the horizon other than zero means that spacetime on the bulk has a finite number of degrees of freedom - in other words, we’d expect that there will be regions of spacetime somewhere beyond the horizon that are not classical, ie not smooth and continuous. Thus, GR breaks down there, which is why we have a singularity appear in the theory. So to me, the very concept of a finite entropy being associated with the horizon means that the bulk it encloses cannot be fully classical.

-

Why does gravity cause acceleration?

It doesn’t. When you put an accelerometer into free fall, it will read read exactly zero everywhere and at all times. There is no proper acceleration in free fall, and thus gravity isn’t a force in the Newtonian sense.

-

State of "matter" of a singularity

There are many different kinds of wormhole spacetimes - some are geodesically complete (no singularities), some have singularities at the centre, and some have singularities at the throat. So it all depends on the boundary conditions. My point was simply that the concept of boundedness is different from the concept of geodesic completeness. A singularity is not a boundary. I’m not really sure what you’re asking here - the purpose of the light cone is only to depict causality. It shows which regions can be causally connected to a specific event. Imagine that at the point of origin (the event) a signal is emitted in all spatial directions. After one second (straight up the time axis), the signal wave front will have travelled a maximum of 300,000 km (straight across perpendicularly) as measured from the origin - iff it was an electromagnetic or gravitational wave, otherwise it’s less distance. After two seconds it will be 600,000 km, and so on. That’s how the cone comes about - everything within the cone is causally connected to the event, everything outside the cone is not, because the speed of light is limited. The surface of the cone itself is a null surface - it represents the boundary between causality regions, and only light/gravitational waves can reach the distance from the event represented by the surface. You get the cone by plotting distance vs time, because the signal propagates in all spatial directions equally. In actuality it’s a hypercone, since we can only depict two spatial dimensions on the diagram. The reason why the light cone tilts and narrows near a BH is because orthogonality and distance between coordinate axis is defined via the inner product - which explicitly depends on the metric.

-

Testing for an aether !

The existence of an aether - I presume you mean the luminiferous kind - would imply a violation of Lorentz invariance, and thus also of CPT invariance. This has been extensively tested for to very high levels of accuracy: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Modern_searches_for_Lorentz_violation Based on the fact that all these experiments came out negative, I can pretty much guarantee you that whatever it is you have in mind will also come out negative. In all likelihood, your specific experiment has already been conducted in some form anyway. Your concerns are misplaced - these tests have all been done already, this isn’t a new thing.