Everything posted by Ken Fabian

-

Asteroid defense ideas

Just my understanding that evolution of a gravity bound cloud of material should settle into a ring (or possibly more than one) that can coalesce over longer time into a second object or more than one. I think much will depend on how much total rotational momentum of the "system" created and I don't know what the time scales would be to become a ring... centuries, millennia, more? I would expect that close proximity detonations would explosively vaporize surface material and the shock wave of that will travel through the object. I'm still inclined to consider penetrating munitions, even as a preparatory first strike ahead of a second dispersing nuclear blast; if there is one area of engineering that we don't stint on, that we are very good, at it is weaponry. A real asteroid threat would be worth more than one device.

-

Asteroid defense ideas

@zapatos If detonations can't give loose rubble enough impetus to escape it's own gravity that would be a mission gone wrong. Avoiding missions going wrong would be important. I'm thinking of what happens with inadequate dispersal, with rocks moving about within a weak gravity well - I would expect any bits coming back in towards the centre of gravity will bounce off each other, not coalesce, some gaining enough momentum to escape in the process, some losing it and orbiting closer. I expect it would take a long time to settle and I think any persistent configuration is more likely to end up as 2 or more smaller rubble piles orbiting each other, possibly after a long time as a larger one with a ring before that. Significant solid portions within what we think (wrongly) is loose rubble might be very problematic. Detonations intended to disperse will be external, on one side, with shock waves within the asteroid as well as rocks outgassing and a range of directions for pieces dispersed, with variable speeds. That would not be like an inadequate detonation placed at the core where the material goes out and a most comes back the same direction. Which I think would make a cloud of loose material that, again, would "coalesce" as a ring with enough time. Yes, sorry, I missed a few posts along the way and was thinking of asteroids from further out. The asteroids that orbit near, inside and just outside Earth's orbit do present challenges for detection but I wouldn't think those are insurmountable. The challenges for any deflection might turn out to be less for such asteroids as long as we have the early detection due to lower delta-v requirements to reach them. Detection will need to move beyond Earth based observatories to get as complete a database as possible - and improving detection is surely the immediate priority.

-

Asteroid defense ideas

Seems to me that would give us more time, not less. And I expect it has happened - and equally likely to reach us that way as inbound. Large objects should be identifiable from any direction and well before any passage around the sun - and identifying and tracking should be (and is) the space agency priority. And (not sure) but may be potential for gravity sling and more effective deflection with less energy can be done when it is closest to the sun? The Nuclear Devices for Planetary Defense link does suggest potential for explosive dispersal and also that a late response might have little choice but to rely on that. I can't see that as likely; the gravity of such objects - even the large ones - is small. Even if it doesn't disperse most of the debris that isn't dispersed will end up orbiting, not coalescing.

-

Asteroid defense ideas

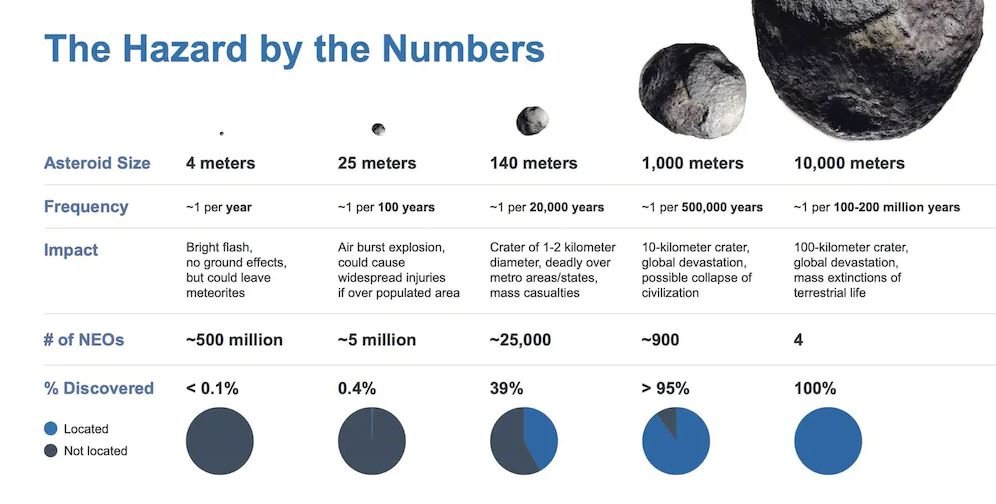

Not missed out but it doesn't stand out as an option except in the sense that at small scale it would be the easiest to attempt using existing technologies. According the the Nuclear Devices for Planetary Defense link (included in the quote I used - KI being Kinetic Impactor) - 605 metric tons is a LOT of mass to launch, far beyond existing capabilities. And (if I understand it) high speed impacts shed a lot of energy as heat and explosively, not all will be delivered as changed momentum in line with the direction of the impact. Not necessarily a problem and possibly advantage if sideways deflection does it better. I still look at meteorite defense as a longer term challenge; yes one could be identified tomorrow but the odds favor not. In terms of odds a too ambitious "being prepared" program could look like waste - Note that this looks at risks from objects within the solar system - there remains the possibility, if very low likelihood, of large objects from outside the observable solar system.

-

Asteroid defense ideas

I'm with Airbrush on this and think nuclear devices delivered by variants of existing rockets would be the preferred means, probably the only one possible any time soon. Longer term - and I do think meteor defense is best viewed as long term - other options may become possible. Delivered and it is done versus delivered and just getting started. Much more deflection from less payload. Shorter mission times. Uses familiar technologies with lots of existing knowhow and capability. The links people have provided, including yours appear to support that although different asteroid examples and different units make direct comparisons a bit tricky - at least for me. https://arxiv.org/pdf/physics/0608157 with Apophis (320m diameter, 46 million metric tons) as example for a 1 ton gravity tractor - 3.7mm per sec per year (? Someone else should check units and arithmetic?) https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20205008370/downloads/Nuclear_Devices_for_Planetary_Defense_ASCEND_2020_FINAL_2020-10-02.pdf with 560m diameter object and 550kg payload - 65 to 165mm per sec in a few seconds to minutes with a single 1 megaton nuclear device for a significantly larger object. Having the device stationary with respect to the asteroid seems to be preferred over one coming at it at high velocity but not sure how that would work directly along the trajectory.They look to smaller than 1 Mt explosions as preferred - several small ones better than one bigger one. Spinning object? Having a quick search for rotation rates - it sounds like a large rubble pile would max out at 1/4 rotation per hour, slow enough for a nuclear detonation to give directional push. Small ones would be suitable for dispersing blasts. Too close to Earth? The "nuclear devices" paper deems several months of warning as a short warning, late response scenario and doing the detonations more than a month out from expected impact is considered a rapid response. I can't see that as an EMP risk to Earth that far out. Anything as close as the moon will be days at most away - too late, kiss arses bye bye. Nukes not designed for use in space? I expect some probably are even if that isn't advertised; the potential for nuclear warfare to happen in space has been known a long time; it may be against arms agreements to put any into space but military planners always look beyond existing treaties if only on an Irish basis - to be sure, to be sure.

-

Asteroid defense ideas

I can see why you might think that - a course that 'begins' where it crosses Earth's orbit ought to be an orbit that crosses that orbit again. But orbits aren't really that precisely repeating, with precession etc. Any deflection that reduces or increases it's velocity along its trajectory for example will result in orbits that probably won't ever come close again. This seems like an experiment that would be worthwhile running. I'd still look at penetrating munitions too, to see if we can blow material out directionally.

-

Asteroid defense ideas

Well if you read on I did add 'maybe'. The first link I looked at was to estimates of what a 1 ton spacecraft could do, without including any estimates of how much fuel or reaction mass or the time and fuel to get it into place; I think those will be significant. A thruster on a broad pad would allow higher thrusts, to the limits of the asteroid's integrity and I suspect it doesn't matter which way the orbit gets altered, that if it is changed in almost any way (except maybe intentionally in particular directions) it won't be a future collision hazard, so thrusters could be placed at one of the poles to allow continuous push. But, again, I am doubtful rockets pushing it or pulling it would be a preferred approach and the time and rocketry constraints will favor other means. Maybe even a different approach, like an up-scaled version of this to toss rocks at faster than escape velocity, plus a robot to load them into it -

-

Asteroid defense ideas

No it won't. Deflection at any point in it's orbit will make a new orbit and new trajectory and it will be less likely any Earth crossing orbit object will ever cross Earth's orbit again.

-

Asteroid defense ideas

MigL (and not only MigL) makes a good point - the objects will be very different in composition as well as size and make very different challenges. Likewise for Earth orbit crossing asteroids with knowable orbits, (lots of lead time and potential to rendezvous on it's way outwards between perihelion before aphelion with much lower delta-v than the other way) and incoming comets or asteroids out of deep space that give much less warning. Different too between one expected to hit on it's inbound approach or hit outbound after perihelion and passage around the sun. Potential for solar electric propulsion. Rendezvous with an object from far out on the inward approach before Earth's orbit needs a lot more delta-v to match course further out in the solar system and solar electric propulsion would not help. If collision is predicted for after passing around the Sun then rendezvous between Earth and Sun and nudging it as it passes closest to the sun may give some potential gravity slingshot gain - if that is possible. But any approach that requires a rendezvous uses a lot of energy moving a spacecraft into matching trajectory, energy that could be delivered DART style more directly. Still not convinced much is gained by gravity tractors over direct thrust, with a broad pad, mat or mesh to spread the load. Maybe. But I am actually more doubtful that any kind of slow thrust will be preferred, however "mounted", as compared to other approaches. If it is not huge and is loose rubble (looser will tend to go with smaller) and there is enough time to use Gravity Tractors then I expect explosive scattering would still do the job quicker and more reliably. Nothing delivers more energy or makes more energetic explosions than thermonuclear detonations - and much more energy can be delivered that way for similar payloads. It isn't just the mass of propellant for GT snigging (Aust/NZ term for dragging logs by chain or cable) but the propellant to get there. DART style kinetic energy transfer seems to have a lot going for it. On a first consideration it seems like a kinetic impact would simply transfer momentum directly opposite to the impact but (if I understand it) a high speed impact sheds a lot of energy explosively and that is outward from the object's surface in meteorite style - so a tangential impact should blow material sideways to the direction of the impact and direction of the object. Whether the changes are better tangentially or by reducing (or speeding up) the object by a front-on or rear-on blast isn't clear to me; it could be effectively equivalent. Mention was made of penetrating munitions; loose rubble piles would be especially susceptible. Any kind of solid metallic ones, maybe not so successful. Sorry, this makes no sense. Likewise there are no straight trajectories - every time it will be a moving object aiming to meet a moving object where their gravity-curved trajectories cross.

-

Asteroid defense ideas

I can't see how this can work, let alone more effectively than mounting thrusters on the object . The thrust is very low, no more than what it takes to hover the rocket over a very low g object, even leaving aside having a rocket exhaust aimed at the object. Sure, it won't break a loose rubble pile apart but it won't move it much. Thrusters mounted on the asteroid, used to the limit the object can take will do more. But I don't think thrusters will work either. I don't see how boosting a very large mass a vast distance and into a specific course in a whole different direction and (critically) giving it all that delta-v to get there could be better than boosting the object itself (which doesn't seem viable). Given that mass of rockets + payloads are far exceeded by mass of fuel (or reaction mass) that gets used and discarded along the way you better make the payload something more useful than the gravitational attraction of it's mass. That still takes energy, a lot of it to spin a large mass (and a big asteroid is a huge mass) even before achieving enough spin to fling anything. All wasted; any capability to give sideways thrust on the object's surface could be better used to launch material away directly, as deconstructing or as a kind of reaction rocket. Or just used directly to shift the course of the object. If enough time and distance I expect nukes could blow them into a debris cloud wide enough to be low risk - or we could use less than object shattering detonations for blowing asteroid material out directionally as a means of shifting it's course. Aside from that I am struggling to see what would work. It seems clear that to have any chance there has to be both early warning and the means to do something waiting in readiness.

-

Asteroid defense ideas

All the Earth orbit crossing asteroids in the solar system of that size are known and tracked but if one were lined up for possible collision in one century's time lt seems enough time to dismantle that asteroid and scatter the bits into not-intersecting-with-Earth orbits. Would not be easy - a massive project that probably requires more cooperation than humanity is capable of? And maybe it can be exploded into a cloud of debris too wide and diffuse to be dangerous. If that were to use up the world's stockpiles of nuclear weapons - using them for good whilst getting rid of them for good would be good. Too good I expect. Something unknown, ie from far out, won't give that much time - a few years of warning (maybe) to do things that will... take a few years to do. If I understand right if the debris isn't scattered wide enough it can be as bad as hitting as one mass. A different kind of won't be easy, with a lot more urgency I suppose.

-

Overpopulation in 2023

My own view is that the lifestyle choices of the wealthy are much less significant than their investment and business choices - and I can forgive a lot personal extravagant wastefulness where they commit their businesses to reducing emissions and environmental footprints. With a shift to low emissions primary energy any direct link between consumption and emissions gets attenuated - the solution to air travel emissions being low emissions aircraft rather than forgoing air travel. There are other environmental costs and issues - but I think it doesn't help to focus on the personal lifestyles of (the exceptionally rare) wealthy person who advocates for climate action, for supposed hypocrisy when so many others are extravagantly wasteful and advocate (in ways that those without wealth cannot) against climate action. The latter may not be hypocritical per se, but their rejection of responsibility and accountability looks like a more significant ethical failure. The former may well support the development of low emissions aircraft where the latter oppose it.

-

Asteroid defense ideas

Anything really big is going to present serious problems - but on the other hand they are easiest to detect. Mostly the biggest ones have been identified - and cleared of suspicion. Getting precise course prediction from as far out as possible will be important - identifying one aimed in the vicinity of Earth will include near misses too until it gets closer and you better not change it's course only to discover later that you've aimed it more closely rather than deflecting it away. I don't know to what extent changing albedo can be useful - spreading black soot over part of a comet could trigger more outgassing, or white coating to reduce it. For the stony and metallic objects, no. Any "light sail" effect is probably going to be extremely small. I think any gravity effect from a spacecraft will be extremely small too; if we can move enough mass to the vicinity to change it's course it seems to me we will be better usign that capability directly to move the mass of the object. Not convinced the net idea is any help - keeping impulses, however made, below the threshold for breaking loose "rubble pile" types apart seems better. Unless they are small enough that breaking them apart is a viable option - larger ones being less likely to be rubble piles in the first place.

-

Curious device

I once tried building a "perpetual motion" machine not too dissimilar - not because I thought it would work but to work out what I was missing, to understand why it wouldn't. Needless to say it didn't work and I saw the push of magnets equaled the pull, with friction as well.

-

Over 95% of this year’s US planned electric capacity is zero-carbon

Seems like a tipping point on relative costs has been crossed. The economics of renewables has never been better and that has to be the case for massive growth of it to be possible as a policy. Not so much deep, long planning as taking advantage of the extraordinary cost reductions for RE; even one decade earlier and the IRA would not have been possible. I think carbon pricing can only work if there are available alternatives for energy companies to invest in that are approaching cost parity - which is only recently the case for RE for much of the world and is more difficult for a nation with extreme winters like Canada to take advantage of. More long connectors to the USA to take advantage of cheap solar out of season? More wind and hydro? More nuclear? But sticking with fossil fuels is not a good option.

-

Anyone traveling to see the eclipse?

I'll wait until one happens where I am - 2030 looks good for here. The last time I was where a full eclipse happened (suburban Sydney) the hush that descended was a surprise - most people headed inside (to watch on TV?) and the traffic mostly stopped. It seemed like some people were spooked (and fearful for children) as much as they were interested and the park we headed to was nearly empty, only one person with a telescope. Didn't have the gear ourselves to view directly - but did the pinhole thing and saw the impression. Mostly we observed the effects, like the sharpening shadows as it became a crescent, saw stars and watching/listening to birds, some doing their morning calls as the light came back.

-

do you believe in future and useful h2-airship?

I think the vulnerability of airships to bad weather is their greatest weakness and that isn't different by using hydrogen - there are uses for them but they are limited. I am still a bit surprised there haven't been serious efforts to use hydrogen by improving ways to do so safely; I am sure it could be done a lot safer than a century ago. And most zeppelins back then never caught fire. Dramatic examples of things going wrong don't necessarily mean they are very likely or cannot be avoided

-

The predominant color of the flora and plant organisms of a planet in relation to the type of star it orbits and the wavelength it generates.

@CharonY That is interesting and shows I don't know as much as I would like to. Thanks. Some green light gets used by photosynthesis yet a whole lot of green light goes unused by Earth's dominant plants or it would be absorbed, not reflected nor pass through leaves so much; I am still inclined to think the biochemistries that can do photosynthesis well could be limited and stronger green light won't necessarily lead to plants that use more green light more effectively.

-

The predominant color of the flora and plant organisms of a planet in relation to the type of star it orbits and the wavelength it generates.

A different opinion here. I expect that the light from other stars will still have a lot of energy across the whole visible spectrum, that eg Blue stars don't make only blue nor have a pronounced lack of red light in the spectrum and Chlorophyll a and b would work just fine. Despite the amount of energy available to Earth plants between Red and Blue they have not evolved photosynthesis that utilises Green effectively, despite the great abundance of green light - the limitations may be in the kinds of photosynthesis chemistry that work and the other, non chlorophyll sorts of photosynthesis (some not doing CO2 to O2) are less effective. Maybe plants elsewhere will manage with Red and Blue photosynthesis (and look green like here) because those kinds of photosynthesis are easier for biochemistry to achieve.

-

How many M-Type asteroids will Earth (truly) need?

@Carrock Seems to me we would try for Near Earth Objects (NEO's) by preference. Atiras asteroids are inside Earth's orbit around the sun without crossing it, Atens are inside but do cross it, Apollos are outside and cross it and Amors are outside and don't. They seem likely to have recurring "windows" where lowest delta-v will be possible. I wouldn't start with the Asteroid Belt. I've suggested C-type (carbonaceous) asteroids by choice, for the water content (for reaction mass) however in general those are more likely to be found further out in the solar system and the Near Earth ones more likely to be S-type (stony). All probably contain nickel-iron but whether they contain carbonaceous or others suitable for extracting fuel/reaction mass is not clear. But the fact that carbonaceous meteorites are common suggest that carbonaceous asteroids could amongst those NEO"s. And if going further afield then there are Mars' moons, which appear to be carbonaceous. Any potential target would deserve some survey sampling.

-

How many M-Type asteroids will Earth (truly) need?

@Phi for All There may be imaginary "better" uses in space - never any shortage of those - but the only advanced industrialized economy that actually has high demand and high value uses for PGM's and can pay for them, the only one at all - is Earth's. The 'but we can use in space' is sort of right; most of what any proposed asteroid mining operation produces will be for use in space, as essential to being able to deliver resources of high value to Earth - like fuel for the rockets. There is no independent space economy only outposts of Earth's economy. Sure, if my proposed test case worked it could deliver small amounts of usable asteroid materials eg water, raw nickel-iron, carbonaceous material to NEO there could be demand for them from whatever space stations there are. But what are those space stations doing that makes a profit? I've asked this before but no-one can answer without getting all imaginary. Taxpayer funded space stations that make no profits using such materials may reduce their costs doing that, but the overall totality still relies on Earth subsidy, just a bit less direct. I don't think any projects in space can achieve self perpetuating growth unless the economics work. What are those activities in orbit that pay their own way with enough left over to support future growth? Subsidy until it works isn't good enough; we need a lot better than that to commit the levels of investment needed. Without a way to deliver tangible returns to Earth investors it is just dreaming.

-

How many M-Type asteroids will Earth (truly) need?

@GeeKay the alleged values don't mean much and any mining attempts, if ever, are likely to start small and probably continue to have a lot of very high costs to recover before achieving profitability - and not much affect the market price. I am amongst the more pessimistic commenters when it comes to space but the resources in asteroids are real - notably Platinum Group Metals mixed in nickel-iron at 10's of parts per million (going by meteorite samples). Even the nickel-iron, raw and unrefined would be considered valuable here on Earth, just for the nickel content. Most things in space have no potential to make money but asteroid minerals are a real "prize" of enormous potential monetary value, so I think the interest will always be there. Yes, the differences in velocities are huge; most of any asteroid mining/refining operation would be making enough fuel/reaction mass for the rockets, which must have exceptional durability and long working life. That is probably the first test that needs to be passed - a rocket that can do a round trip between asteroid and LEO exclusively with "fuel" (and other consumables) produced out of asteroid resources. And do it over and over reliably with absolute minimum of ongoing supply from Earth. Probably not an M-type. We need to know what those rockets will run on and know if a target asteroid has it. Off the top of my head I would target C-type; going by carbonaceous meteorites they contain the target mineral - nickel-iron with PGM's mixed in - as nodules and grains within a softer carbonaceous material that also contains significant amounts of water. Can solar electric arc-jets use simple water for reaction mass? H2 + O2 chemical rockets present serious problems, including very large tanks as well as, ultimately, inadequate performance. I think things get harder if any rocket uses requires more exotic fuels, eg the Keck Institute of Space Studies proposal to capture a small asteroid and return in to near Earth space with a solar electric rocket using (if I recall) xenon for reaction mass. Seems very unlikely to find a source of xenon in an asteroid. Hydrazine is used with arc-jets and it seems possible (with water and a source of Nitrogen and equipment) to manufacture it, but water, even if less ideal, presents a simpler challenge to produce and store and use.

-

Growing forests double quick

Close planting - more like 1 per m2 rather than 5 - is common practice for forest regen projects here in Australia, and I expect worldwide. It mimics the mass germination and growth from broken canopy in natural forests. Attrition is of course part of that; you end up with a very few mature trees. The pre-colonization mature forest where I am (if I am recalling correctly) was around 6 to 12 trees per hectare. Big trees. The regrowth forest present now is in between - maybe near a hundred trees per hectare after much higher numbers of (naturally germinated) seedlings and saplings. Had the original land clearing intention been followed through the regrowth would have been prevented as far as possible and over time the soil seed bank would deplete - and planting becomes the only way. But natural regrowth favours some species over others; there is no expectation that what will regrow will have all the same species in similar proportions. And some species never really recover, including some of the most prized timber species, that were mostly gone before the land clearing and haven't and won't ever recover. The glib cutting trees down promotes new trees, more than before defense of widespread exploitation of old growth forests was and is a half truth; we get lots of smaller trees dominated by a few species and the ecosystem is different to the original.

-

Growing forests double quick

I'm not sure we know how any typical forest planted now will be faring in 200 to 300 years; do we choose which species to grow based on what the climate is now or what we expect it to be? Sounds like a concept with benefits to farmed and gardened forests but not necessarily useful at very large scale. There are good reasons to have forests and natural ecosystems but emissions mitigation isn't one of them. I think it is more appropriate to think of the CO2 reforestation sequesters as counting towards reductions in land use emissions rather than to justify ongoing fossil fuel burning. The impacts on emissions of mass forest plantings are going to be complex but ultimately they'll be finite and won't exceed what was emitted from prior deforestation; this kind of forest cultivation might take down the Carbon faster but it will reach peak biomass faster and stop being a carbon sink sooner. I don't think we can depend on sustained, non-reversible increases in global biomass to make a significant difference to the climate problem. If it doesn't reduce fossil fuel burning it isn't fixing the climate problem. And in my view it is a travesty to plant forests in order to protect fossil fuels from global warming.

-

EU to tax carbon in imports

To be serious about zero emissions we need these kinds of mechanisms in place in the world's major trading economies. Preferably pricing at rates like we really mean it, that ramp up predictably over time, like we mean it and without rafts of exemptions and exceptions, like we really mean it. But anything tariff related gets bent by geo-political concerns and I fear that anti-China sentiment will be used expressly to impede global growth of RE and EV's, in ongoing efforts to save fossil fuels from global warming.