Everything posted by studiot

-

Help for chemistry assignment

Good morning. What subject are you studying this in, and at what level ? Is it General Science or something at higher level ? Muriatic acid is a very old name - in all the 60 years since I have known anything about it I have never seen the name used. So I will try to address other older conventions in my reply as well. The quantity of substances can be measured in several ways : weight, mass, volume (also called capacity) count (eg gram-moles) or pressure. Since the substances may be in any of the three normal states of matter (solid, liquid or gas), or the dissolved state some measures are more convenient than others. When you come to mixtures there is a comparison of more than one substance quantity and the units of measure can themselves be mixtures of the above listed measures. Common measures are weight per volume (w/v) ; volume per volume (v/v) ; weight per weight (w/w) ; and moles per volume (mol/litre) So you should look carefully at the labels for one of the above abbreviations on the labels you are told to read. Without this information you cannot answer the question. When it comes to percentages, unfortunately different industries use the % in different ways so my preamble is important. Here are two different listings for 18% HCl - one is w/w the other is v/v Either way the % is a fraction of the total amount - which is the sum of the water and the HCl in a given mass or volume Your 18 % Hydrochloric acid is a common cleaning concentration in engineering and often refers to what is called the mass fraction - a w/w measure. It means that of the total mass, 18% is HCl and the rest is water. So Mw is the mass of water and MHCl is the mass of HCl then [math]\frac{{18}}{{100}} = \frac{{{M_w}}}{{{M_w} + {M_{HCl}}}}[/math] or [math]\frac{{18}}{{100}} = \frac{{{V_w}}}{{{V_w} + {V_{HCl}}}}[/math] for the volume fraction You should be able to solve this for the mass of water. Does this help ?

-

Concerns about the geometry of the real number line

This is a beautifully crafted paragraph that should be studied very carefully as it contains lots of useful and important information. +1

-

Concerns about the geometry of the real number line

So which is it - countable or uncountable ?

-

Concerns about the geometry of the real number line

Nice. +1 Good Infinity is not a number. So it cannot be a member of either the set of reals or the set of naturals or the set of rationals or the set of integers. So why do you claim infinity is a number ? None of the elements of set of reals or the set of naturals or the set of rationals or the set of integers are infinite. You are confusing the sets themselves which are infinite, whith the elements of those sets The elements (ie the numbers themselves) are all finite, without exception. You misuderstand what is meant by infinity. So it is as pointless to want to use ZF theory as saying "I have never used a chainsaw, but I am going to take one, climb a 30 foot tree and start cutting". I was so very disappointed with this response that I considered your 'bail' option as I am no longer sure whether you are only trying to find fault here or actually trying to understan. Understanding takes effort on the part of the student. Yet you have uttered not a single word about inheriting key properties. Have you tried the simple proof I suggested ? You suddenly mention continuums. These are not like continuums in 'continuums' in physics or 'continuum mechanics'. The 'Continuum Hypothesis' is suprising in what is actually hypothesised, Just as the ZF axioms are suprising in their names and statements. Have you ever worked with any ?

-

Concerns about the geometry of the real number line

The point here is that, after we go beyond the integers, we are never looking for a 'next' number because we never start with just one number. We need to employ two numbers. It works like this. All number systems inherit properties from simpler systems from which they are built. We cannot build the integers without the natural numbers. We cannot build the rational numbers without the integers. I will take these as read and proceed to the rational numbers. We define a rational number as the ratio of two integers. It has to be integers since we are defining 'fractions' so we cannot employ fractions in our definition or it would be a circular definition. We define one rational number a/b as being greater than another , c / d, where a,b,c,d are all integers [math]\frac{a}{b} > \frac{c}{d}\quad if\quad ad > bc[/math] We can use this to find a third rational number between any two rational numbers as [math]\frac{a}{b} > \frac{{a + mc}}{{b + md}} > \frac{c}{d}\quad if\quad b,d,m\;are\;positive\;{\mathop{\rm int}} egers[/math] I suggest you practice some algebra by convincing yourself my formulae are good. We can repeat this process indefinitely, placing a fourth rational number between our first and third or second and third rational numbers. This leads to the conclusion that between any two rationals there is another and by extension infinitely many other rationals. This density property amounts to saying that, for the rationals, there is no 'next' number to any rational since given any proposed next rational we can place another closer, by this process. So let us move on to the set (I learned class) of all rational numbers and divide it anywhere into two subsets. This is actually where a number line comes in handy since we can call the subset to the left of our dividing line L (with typical element l) and the subset to the right R( with typical element r). Because we have divided the line to the left and right, any l < any r. Now for the clever bit. If we pick one rational from each of L and R, say l and r then we can examine the infinity of rationals between l and r according to our formula above. Each and every one of these must individually belong to either L or to R, but not to both. There can be no rational numbers belonging to both L and R. This means that we have an infinite sequence of increasing rational numbers greater than l in L And an infinite decreasing sequence of rational numbers less than r in R So L has no greatest element And R has no least element So we have created two open sets and sequences a la Genady. This density property is inherited by the reals from the rationals, as noted at the beginning of this post. As also noted the fun starts when we try to incorporate irrational numbers into the scheme as the next post will show, with the story of root2 - the first irrational to be discovered. Again this is where geometry helps explain things.

-

Physics and “reality”

Since I first mentioned Lorenz I should point out that I was talking about the Lorenz Transformation, not the Lorenz force , which is an entirely different phenomenon.

-

Physics and “reality”

Good one, thank you. +1 But remember that sometimes only one or two are satisfied for example Newton's third law. Ths can be equally interesting, as in maths.

-

Concerns about the geometry of the real number line

The point is that you need to set the stage you are working on. That is the point of all the different offereings about open and closed sets, squences and so on. In what circumstances are you looking for a next number ? My stage is concerned with what are numbers? and what properties do we want them to have ? Thank you that I hope that is useful information to everybody. I expect he alsotold you that each Aleph is the cardinality of a particular infinite set of numbers. And perhaps he also made the point that it is not necessary for the cardinal number of the set to be an element of that set. I can be for finite sets, but it can't be for infinite sets. So often we all read something into what someone else has said, that was just not there. I do it, though I try to guard against it. In this case I specifically said the opposite To return to my stage. The thing about the rational numbers is that they have the same property we are examining as the reals, which is called density or denseness. Density should not be confused with completeness. In colloquial terms density means that between any two rational numbers we can find another rational number. This is an easy 3 line algebraic proof/demonstration if you want it. So the rationals also have this property of no nearest neighbour, assuming you have decided what you mean by 'nearest'. So what is the difference between the rationals and the reals ? Understanding this difference is the great step forward that Dedekind took when he published Stetigkeit und irrationale Zahlen, Braunschweig, in 1872 Yes WTF is correct in that Dedekind Cuts (Schnitt) divides the entire set of numbers into two subsets, but there is more to Dedekind than that. The fun begins when you try to determine which of the two sets a particular number belongs in. I was trying to avoid implying that 'isolating' every number in its own partition means just two partitions, I simply thought that perhaps you were half remembering something like this.

-

Physics and “reality”

Thank you, I was referring to Rutherford's experiment, conducted in a single frame. https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/General_Chemistry/Map%3A_Chemistry_(Zumdahl_and_Decoste)/02%3A_Atoms_Molecules_and_Ions/2.04_Early_Experiments_to_Characterize_the_Atom

-

Physics and “reality”

Thank all you good folks for your thoughts. I fear this is becoming a semantic or interpretive issue as to whether or not there are mathematically defined equivalence realtions is Physics, and this was not what I meant when I posted My main point is that reflexivity, symmetry and transitivity are valuable notions that could have wider applications regardless of whether we are talking about interactions, relations or some other phenomenon. I would also remind you that the zero interaction, relation, whaterever is acceptable in maths so should the zero interaction be acceptable in Physics ? E.G. Gamma ray do not interact with electric fields ? I am suprised that @swansont doesn't appear to have a view on this, as I would value hearing it.

-

What is classical physics?

I think that sufficed for the mid 20th century. We are more than half a century beyond that now and a whole century since the main work of Einstein, Planck et al. It was always an arbitrary distinction, and modern science and physics moves on. So many matters in older disciplines macrocopic or microscopic involve some measure of quantum theoury, some measure of new science such as data correction (the James Webb telescope couldn't funtion without the latter. We really need some new categories to clear up the mess.

-

Concerns about the geometry of the real number line

What sort of professor was this fellow and what level mathematics was he teaching ? If and only if [math]{\aleph _0}[/math] is a number then you can add 1 to it. That is the most basic property of any number system there is. However I suggest you forget the alephs because none of them are real numbers, unlike the numbers I have been using. I did not say natural number, 1 ,2, 3, 4, 5 , 6 , 7 ,8 ,8, 0 are all real numbers. I said several times I am using these because it is simpler. Using 1.05788 for instance sould be done but obscures the real point of a statement. Yes and it states quite clearly that this you have to have cartesian coordinates to execute this procedure. Numbers do not have cartesian coordinates. On the real number line, the value of the number is the same as its distance from ther cartesian origin of the geometrical object we call the real number line. Talking of properties have you thought about reviewing your starting point for this ? You need to distinguish very carefully between the value of a number and some distance you associate with it, because your question is about the value of that number not any associated distance. Nearly two and half thousand years ago it was realised that numbers went on forever and they further realised that there were additional numbers (which they tried to hide) that did not fit into their system. It was not until 1872 when Dedekind published his theorem or axiom that this issue was properly resolved. I have also mentioned the upper and lower bound theorems. Cantor's approach to the issue was one of synthesis - build up the whole from small parts. Dedekind approached from the other point of view - analysis - break down the whole into small parts. His axiom shows the difference between the rational numbers and the real numbers. The real numbers include all the numbers that do not fit into the rational number system - because they are irrational. He proved, using Cantor's set theory, that the real number system is 'complete'; that is there is a place for all numbers in it. The rational number system by contrast is incomplete, known as already noted for a very long time. You can carry on the many of the same processes in either the rational or real number systems, in particular the infinite processes of tending to infinity or the infinitesimal. But there is a second property that makes the difference. Take for instance the square root of 2, probably the most common irrational number. Schoolboys are shown the quick and dirty algebraic proof that it is irrational. But they rarely probe further in to the meaning of this which is that the square root of 2 is not a member of the set of rational numbers. You can never get there by any process infinite or finite since the number just does not exist in the rationals since it has no place there. Infinity by itself is not enough. It is very illuminating to use Dedekind to develop why this is and then go on to the second required property, that of completeness. We can do that together, if you like.

-

Physics and “reality”

Why not ? They have a relative velocity, isn't that a physical interaction between two distinct entities ?

-

Physics and “reality”

How about the Lorenz transformations ? They are equivalence relations. https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/152115/A_novel_equivalence_relation_in_relativity.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

-

Concerns about the geometry of the real number line

Can it ? Let us try some examples. Compare the distance between 1 and 2 and between 4 and 5 by this definition. Distance 1,2 = √(12 + 22) = (1 +4) √5 Distance 4,5 = √(42 + 52) = (16 + 25) = √41 Is this difference acceptable ? If you read my Wiki reference on Metric spaces you would see that there are three different common definitions of distance and the euclidian one is not appropriate here. I have already mentioned the method of Dedikind. This used to be the preferred route to understanding why we can keep chopping up the distance between any two real numbers. The old way was to start with counting numbers, (whose distance betweeen is not infinitely divisible) show why these are not enough ie there are more whole number than counting numbers to get the integers Then progress to show that there rational numbers give us still more numbers the distance between becoming infinitely divisible. But also that there are gaps in between which means that the rational numbers are not continuous. Finally we come to the real numbers which are continuous in that there are no gaps at all such that the real numbers possess the property we call completeness as well as being infinitely divisible like the rationals which are not complete. Being complete and without gaps means that that there are no further numbers to acount for.

-

Physics and “reality”

Further to my last post, this topic makes me think of the mathematical idea of equivalence relations. The idea has wider application than just maths; many physical interactions are relations, but not equivalence relations, in that one or more of reflexivity, symmetry or transitivity ar not satisfied. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Equivalence_relation

-

Physics and “reality”

Do we not also recognise the notion of self-interaction or self-activation for some phenomena in Physics ?

-

Concerns about the geometry of the real number line

Your answer is correct so it is a pity your reasoning is incorrect. furthermore numbers don't 'know' anything. Also I don't agree that you claim about extra drops of water follow from your premise. Surely the answer will be yes.

-

Concerns about the geometry of the real number line

This statement I can agree with. So here is a simple observation. The ancient Greeks realised that If r is a positive number, real or otherwise, then r+1 is a larger number, and (r+1)+1 is larger still and so on. So there is no largest number. Now we also know that if we take reciprocals 1/r is greater than 1/(r+1) which is greater than 1/((r+1)+1) and so on. Since there is no largest number there can be no smallest number either. Sweet dreams everybody.

-

Expansion of the universe or contraction of scale?

A very reasonable question. Have you thought about possible tests ? Interestingly this is made possible because of the finite speed of light. We can look back over much longer timescales than our own lifetimes or even our civilisations'. So we can compare the configurations of matter over very long timescales and we find that the further back in time we look the smaller the gaps are and the average density is diminishing, when directly comparing one with the other so we can say with confidence that the correct interpretation is expansion not contraction.

-

Concerns about the geometry of the real number line

Subject to the comment Genady has already made about Reiman integrals, yes you can and The method is nothing like you seem to envisage and nothing to do with Reiman integrals. First you you should study this article carefully. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metric_space What you are seeking is the method of partitioning a set so that every partition contains exactly one member of the set and there are no empty partitions. This is called the method of Dedekind cuts. But it does not lead to a smallest real number,

-

Concerns about the geometry of the real number line

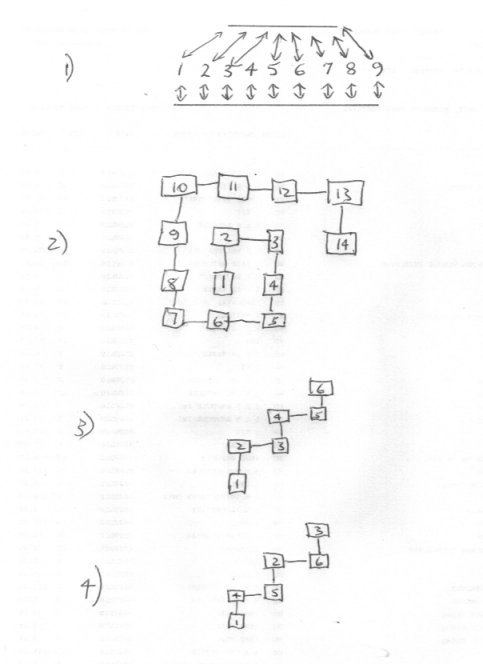

One or two debatable points there but your heart is in the right place. +1 for encouragement @Boltzmannbrain Whilst @Genady is doing such a good job offering straightforward textbook details I think it is worth looking deeper into the number line concept. I will readily grant you that the number line is a very attractive way of presenting aspects of the properties of numbers. But what we are really doing is as in fig1 putting numbers in one-to-one correspondence with a straight line and hoping that other properties are then transferable. But also as in fig 1 it is easy to see that the actual length of the line is irrelevant - it works for all straight lines, regardless of theier length. Radical conclusion : You can establish one-to-one correspondence for the whole set of numbers with the shortest possible straight line, as well as the longest possible. Question : How does this affect you proposed distance function ? Surely the distances apart of any two numbers will depend upon the length of you line. But who says the line must be straight ? Fig 2 shows how to use a spiral to place the numbers. This has the interesting property of being able to cover the entire plane. Question : How does this affect you proposed distance function ? As can be seen in fig 2 - the numbers 2,4 and 6 are all equally close to the number 1, whereas the numbers 3 and 5 are further away. But does the line have to have a definite geoemtric shape ? So far I have discussed straight and spiral. Surely all that is required is that it must not cross itself. Question : How does this affect you proposed distance function ? Can you see why it must not cross ? Fig3 shows one such semi random arrangement. There are an infinite count of such non crossing arangements. What about the numbers themselves. There is nothing in basic set theory to say that they have to appear in the set in any particular configuration. Fig 4 shows a random positioning of the numbers which is perfectly permissible. Question : How does this affect you proposed distance function ? Clearly 4 is the closest number to 1. So that you can have them is value order you have to add further structure to your set of numbers so that you can introduce a 'well ordering' of the set. Your thoughts on this ?

- N

-

Developments in soil science with potential for electricity generation, water purification and soil conditioning

Thanks for the extra info +1

- Developments in soil science with potential for electricity generation, water purification and soil conditioning

Important Information

We have placed cookies on your device to help make this website better. You can adjust your cookie settings, otherwise we'll assume you're okay to continue.