Everything posted by Enthalpy

-

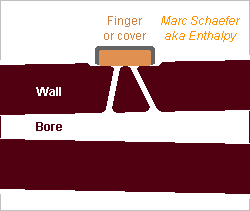

Intentional Losses in Wind Instruments

A woodwind can need stronger losses at some notes or high overtones. Throat notes are an example, where the short air column and its small losses let a reed vibrate too strongly, deforming the sound like a saturated amplifier does. The oboe, clarinet, tárogató have smaller tone holes at the throat to increase the losses there and also to filter out the high harmonics. The saxophone keeps wider tone holes and its timbre changes stepwise at the octave jump. The bassoon, whose tone holes cover two octaves, has very long and narrow tone holes at the throat. Cross-fingerings to play high modes can also harden the sound. On a double reed, small tone holes soften the sound at low modes, but multiple open holes for high modes that keep all harmonics tuned don't remove the strident highest ones, and their losses can be too small for the reed. The bassoon uses detuned cross-fingerings to soften the sound. Finally, woodwinds should dampen the strident partials around 4kHz scienceforums and two previous messages I propose now to split some side holes in two or more. Several narrower holes of same length and total section increase the friction at the bigger surface. Split holes can open the air column at several slightly different locations. This damps more strongly higher frequencies where the air circulates among the holes and acts well before the sum or difference of the lengths is lambda/2. Split holes can combine with the previously explained chambers. A shared chamber would act on many notes in a complicated way. ========== Split holes apply to main tone holes. Maybe Johann Heckel did it at right thumb F-emitting hole for his bassoon, but I have none to observe. The higher hole would usefully be narrower or longer. If an instrument has special holes for cross fingerings mainly, as many systems I describe do, split holes apply to them as well. Split holes might apply to register holes too. They could sit side-by-side, some slightly higher or lower optionally. Sitting at the same height, they spoil as efficiently the unwanted modes with a smaller total section that detunes less the extreme notes. Numbers might follow or not. They are only weak guidelines anyway, and experiments decide at the end. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Materials

Ahum. The boot of my French bassoon is completely different, and for the drawing of Jan 04, 2020 03:58 PM I looked at an old instrument that is NOT the usual U-bend of present bassoons. Yamaha (Fox resembles much) and Heckel page 3/12 These constructions use very little air column length. Not an advantage of my proposal. About the stiffness: The gasket, often cork, brings little stiffness. The screws are stiff but they hold at one end in wood whose shear isn't quite stiff. The other end holds on a metal plate whose bending stiffness decides. Said plate looks thick. Depending on exact figures, which I won't infer from small pictures, the standard design may or not be already stiff enough. As a small variation of the standard design, two elastomer O-rings could replace the cork gasket, especially if retained. Then, a shape that presses the metal tube directly against the wood at the bores, or rather against metal glued on the wood, would gain stiffness if needed. Electroforming would make the intricate shape at once, as already said, but the plate shall not be too thin. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Materials

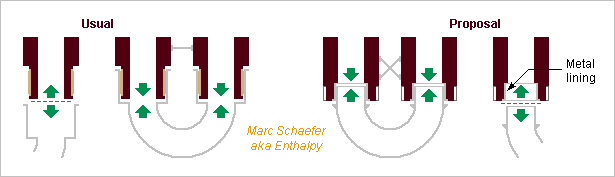

The air column of some woodwinds makes a U-turn: at the bassoon family, the low clarinets, past and maybe future low oboes... The ones I saw are of metal that fits over corks at tenons at the wooden body (the saxophone differs). This must dampen the sound, like cover pads do, because the metal tube is light and the cork soft. I suggest to fit the metal U-turn in the wooden or polymer body with a metal lining, like Yamaha do for their wooden flutes scienceforums - scienceforums europe.yamaha.com The stiff contact between metals should improve more here than between straight heavy wooden flute joints. Very useful too, these fittings are short, so tone holes can have better locations. The metal parts can be electroformed as already suggested scienceforums and followers They probably need adjustment, as for flutes and brass instruments. Wood expands much with moisture and heat, flutes' Dalbergia less, bassoons' Acer more so, while metal expands little. Yamaha flutes cope with that. The metal lining could fit narrowly in the wood at one end and fit narrowly over the metal tenon at the other, possibly with some elastomer there. Or fit the wood at both ends and the tenon at midlength. Wooden joint have reinforcing hoops at their ends, of metal often, of graphite fibres on some clarinets. An adjusted amount of fibres would let the wood fit the metal's thermal expansion. Present bassoons have both bores in a single wooden part. A global hoop of graphite fibres would stabilize the bore spacing. Trumpets can cope with some spacing mismatch. If separate wooden parts make both bores, metal parts can assemble them. Pyramids would stiffen all directions scienceforums - scienceforums Whether the bell of a bass clarinet can hold at such a fitting? I'd rather put the U-turn higher, and some toneholes on a rising wooden joint, especially for clarinets reaching a written C as they're uncomfortably long. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Materials

Here's the flute head stopper I made around 1992 and have been using since. It needs only to turn and bore one part. Mine happens to be Ptfe. The O-rings are banal, maybe Nbr. The metal rod moves the stopper when inserted in the hole. I noticed no difference with the usual stopper, but a decent flute might let perceive one. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Fingerings

-

Woodwind Fingerings

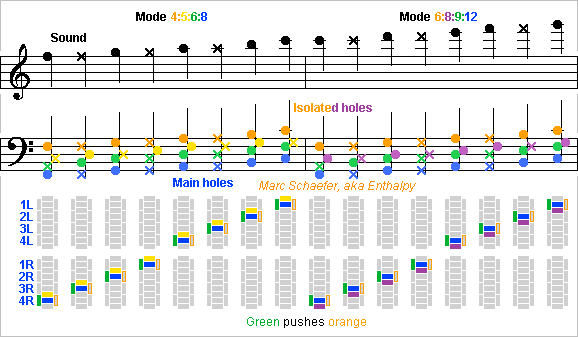

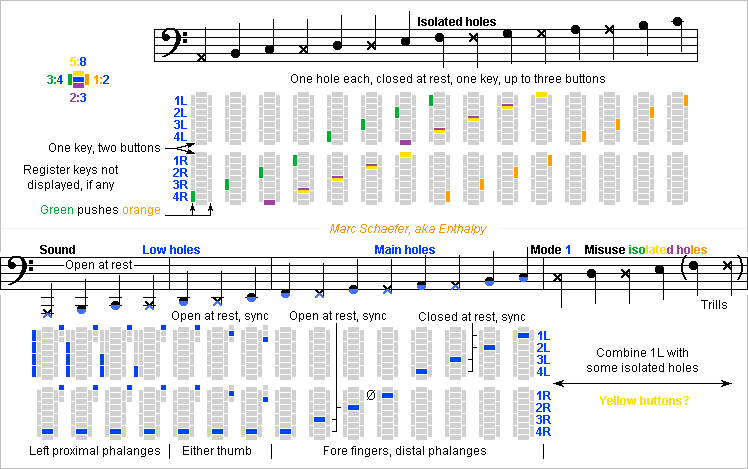

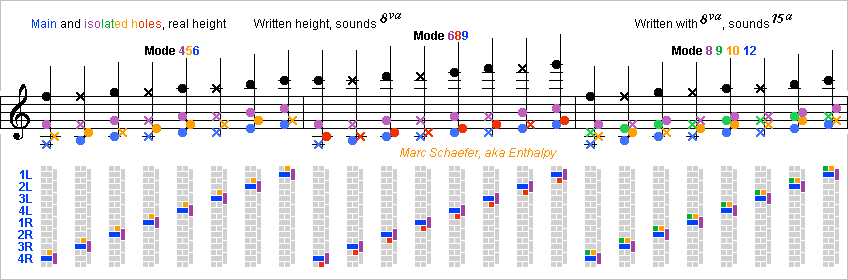

Here's a basson with quasi-automatic cross fingerings system A, loosely inspired by the soprito system F of Dec 15 and 22, 2019 scienceforums and next one On mode 2 and higher, the musician presses one finger at a time, like on a piano to play a single note. The finger's main button closes all main holes above the main transition and opens them all below. By pressing nearby buttons too, the same finger opens isolated holes to easily make the equivalent of cross-fingerings. Bassoons span some two octaves with tone holes, what other instruments can't, and their high holes stabilize the high register. Their lowest 7 holes don't serve for mode 2 but the next ones can be closed even on very high notes. I mimicked that on the quasi-automatic system. Assembling a tenor and a bass joint to a boot would be unreasonable here. The tenor and bass joint hold permanently together and extend to the short removable U-turn. The longer bell has two tone holes. This makes a case as long as for a tenor saxophone, thinner and lighter. Long parts of Liquid Crystal Polymer (LCP) or polyketone are easy, of polypropylene and sycamore too, while Dalbergia is problematic for other reasons. The 4 lowest holes are open at rest. The left fore fingers close one each at the proximal phalanges. The next 3 low holes are open at rest. Three left thumb buttons, replicated at the right thumb, close 1, 2 or 3 holes. The 7 main holes make 8 semitones in mode 1 and, helped by isolated holes, in higher modes. 15 isolated holes on the tenor joint overlap partly the main holes. Each has one key and one to three buttons close to varied main buttons. Yet unknown combinations of the isolated holes shall make higher notes one mode 1 only. Or add main holes for the high mode 1, with buttons at proximal phalanges of the right fore fingers, or at the still underused bassoonist's thumbs. Register keys high on the bocal could occupy the thumbs and help some modes, for instance to favour mode 12 over 8. To synchronize 3 or 4 covers, consider the mechanism I proposed on Jul 02, 2017 scienceforums The spring force must be minimized for comfort. ========== The right fore fingers close at the bass joint 3 main holes open at rest: 1R has a dummy button but real isolated holes buttons, 2R closes one main hole, 3R two, 4R three. The left fore fingers open at the tenor joint 4 main holes closed at rest: 4L opens one, 3L two, 2L three and 1L four. ========== Four buttons surround each main hole button to open isolated hole covers some distance higher than the main hole: 5 semitones = fourth, defining the mode ratio 3:4. 7 = fifth, 2:3. 8 = minor sixth, 5:8. 12 = octave, 1:2. Adjacent main holes and buttons making notes a semitone apart, the isolated hole 8 semitones higher than a main hole is also 7 semitones higher than the next higher main hole, so the same isolated hole and button combine with two main buttons for 5:8 and 2:3. The buttons for ratio 3:4 depress the nearby 1:2 button too to define a ratio 2:3:4. These buttons serve for one main hole button each, but they can combine with other buttons. The lucky combination mimics cross-fingering for modes 1:2, 2:3, 2:3:4, 3:4:6, 4:5:6:8 and 6:8:9:12. Many opened high isolated holes help high notes. Mode 6 (3:4:6) satisfies about any score, mode 8 (4:5:6:8) goes as high as most bassoonists do in stunts, while French bassoons sometimes reach the E in illustrated mode 12 (6:8:9:12) to octaviate the Sacre du printemps. ========== My system A puts isolated holes at better positions than present bassoons do, and spread evenly, while the French and Heckel systems lack some holes and often open several adjacent very long holes for venting and intonation, which can't help the emission. Some of their holes approach lambda/4 length at the high notes, making them inefficient. My isolated holes, one per semitone and specialized, can occupy the best locations hence be made lossy to spoil the unwanted modes. The main holes can't be wide on a double reed instrument, so they will remain very high at the air column. I believe they can be narrower and shorter than presently thanks to covers, and be spaced evenly. Expect them far higher than the isolated holes of same name. The aspect of the instrument could come, later hence maybe. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Materials

The musician must slide fingers from one key to an other at many woodwinds, for instance the thumbs at the bassoon. Coating the keys with nickel that embeds Ptfe powder should help. I let coat steel parts with it, and they were more slippery to the fingers. The good property lasts indefinitely. Nickel provokes allergies to many people, so a different metal that can embed Ptfe would be better. It must resist corrosion. Plain material also exists that embeds Ptfe powder, for instance sintered bronze to make plain bearings. It can't be cast nor brased at high temperature, but machined, filed and soldered at low temperature yes. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Hear Conical Brass Instruments

Thank you! The alphorn is less rare, but without Internet I wouldn't have heard the others. You see the instruments in the museums. But the musicians... There must be few dozens on Earth for each.

-

Hear Conical Brass Instruments

Hello you all! Brass instruments (labrophones) use to have a cylindrical portion before the flare. The longer cylinder and short flare give trumpets and trombones a brilliant sound, the cornet is intermediate, and the flugelhorn and lower saxhorns have a short cylinder and a long flare for deep mellow sound. A air column conical right from the beginning gives also the natural harmonics in tune. But these instruments are rare. The Alphorn is endemic to the Alps, more present in Switzerland, and is normally made of wood. The straight 3-4m are an eyecatcher, but a French horn is as long. It's a natural instrument played on modes 2 to 12 and more. Groups of instruments in varied tunes can complete the notes. Sound: Solo XrO6XVX4C8s at 0:07 and 0:45 - Group 5vxyjLRb0TA - Concerto fXRLjVJQisw starts at 0:44 Valves to achieve intermediate notes are normally brought on the cylindrical portion normally absent from the Alphorn. Adaptations exist right behind the Alphorn's mouthpiece, but I suppose the intonation suffers. The other solution is to have sideholes on the tube, a true rarity at labrophones. The cornett (the one with two t), cornetto or zink is a medieval instrument (or family with varied pitches) played up to the baroque era 0U3jGWLFmsQ Lo son ferito, starts at 0:12 g-7FxTPsR2s improvisation on "Io son ferito ahi lasso" fNfLpwVaAvw Fontana's sonate N°4, more exist The playing technique is lost, there are no professors, instruments in museums can't be played generally, their manufacturing method is lost. If it sounds imperfectly now, blame the centuries only. Among the records I heard, William Dongois (links) has a nice sound and plays more in tune, after both playing and manufacturing efforts. The serpent (snake in French) was the bass, played before the romantic era. The bare tone holes are narrow and they muffle the sound n-Sbq-XL_VU - t9mB72TC8Kw - kieyL2fynds The variant with cups and keys was called ophicleide for keyed snake, it disappeared during the romantic era odQ_Uzmnrns - GG5pbPcXnC0 - hGBmqthNjOs Despite Berlioz recommended in his Traité d'instrumentation to remove the serpent and the ophicleide from orchestras, he used them in his Symphonie fantastique lZzr4xXPeyw

-

Woodwind Fingerings

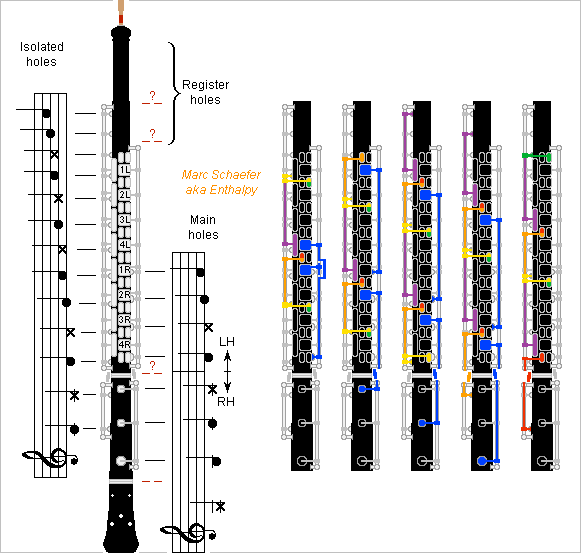

Here's the aspect of a system F soprito with its near-automatic cross-fingerings. Experiments will decide where the side holes are, and the shape of the keys is widely symbolic. Only the three covers for the right hand main covers are open at rest and reside near the body's top line. All other holes are closed at rest. The left hand main holes reside at the right and all isolated holes at the left body side, clearing the way for the buttons. The isolated holes are small and often yellow on the sketch, not easy to find. From the fingering chart, I swapped the right and left buttons, so only the right hand eclipses four isolated holes. The buttons can be offset to match the finger lengths. The notes indicate the fundamental mode of a hole. The soprito uses higher modes. The colours match the previous fingering chart. The isolated hole buttons with two colours serve with two main hole buttons for different intervals. Except if spanning two joints with a transmission, each key has one cover and is brazed as one stiff part, even though the ones with several buttons are represented multicolour. The three right-hand main hole covers are synchronized, the four left-hand ones too, see my proposal there scienceforums With up to three keys aligned over the same axle as on the Boehm flute, four and five axles hold the main and isolated hole keys, hence the five views. I didn't check how easily nor independently the keys assemble on the body. No concentric shafts here, but they might reduce the number of axles. Only one leapfrog, around the dummy 1R button. Register holes, maybe not needed with a double reed, fit all above the buttons. ========== For easier high notes, the bore must be narrower than a saxophone, a bit narrower than an oboe. My estimates suggest that the susceptance of a single reed is then too big, better a double reed, smaller than on the oboe scienceforums I believe a body of metal, Abs, Pp... doesn't fit a high instrument. At Yamaha's Ypc62 piccolo, the grenadilla head eases the high notes over the silver one. Liquid crystal polymer, optionally loaded with graphite choppers, could outperform the endangered Dalbergia melanoxylon scienceforums Polymers make big parts easily, and the soprito is as small as a soprano saxophone, so I wouldn't have a separate joint at the lowest holes then. If needed, assembling a joint carrying register holes seems easier anyway. The tenons could be of silver instead of wood and cork to ease the high notes. It's said to improve wooden flutes scienceforums Fitting the reed on a silver bocal, as on the English horn, would avoid the lossy cork, if small reeds accept that. The bocal must then fit stiff on the body, say at a metal insert, and can hold register holes. Cork pads ease the high notes versus leather-covered felt. All these means harden the sound. Chambers at the holes shall squeeze the strident frequencies selectively scienceforums ========== The pedal notes are accessible without extra holes after all, if using isolated holes as main holes. So shall the same system and a wider bore make a soprano too? I'm not enthusiastic about that. Multiple goals would need compromises and make the isolated holes less good. I don't believe the same reed and bore make a soprito and soprano. For a soprano, my even fingerings and my automatic cross fingerings are better scienceforums - scienceforums - scienceforums Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Fingerings

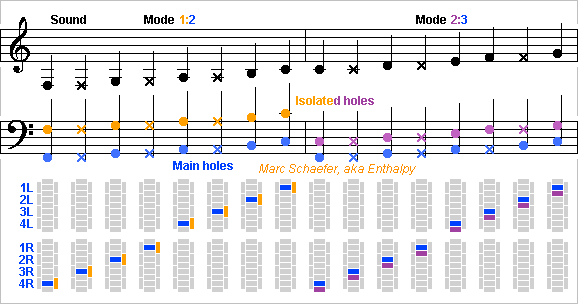

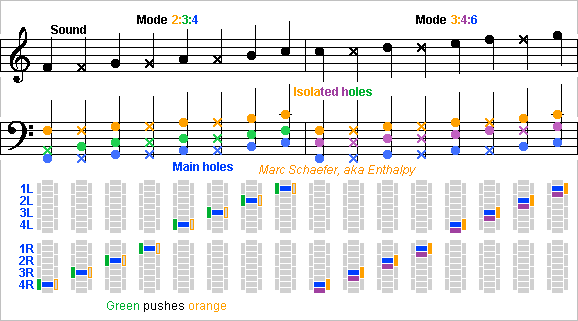

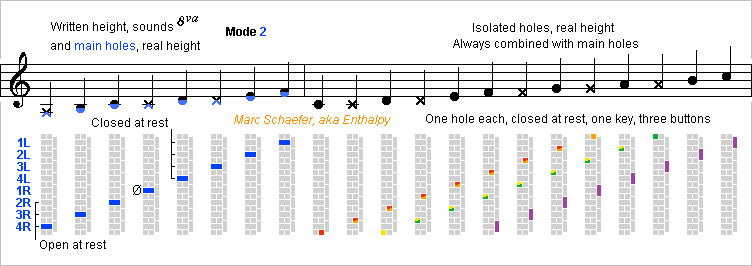

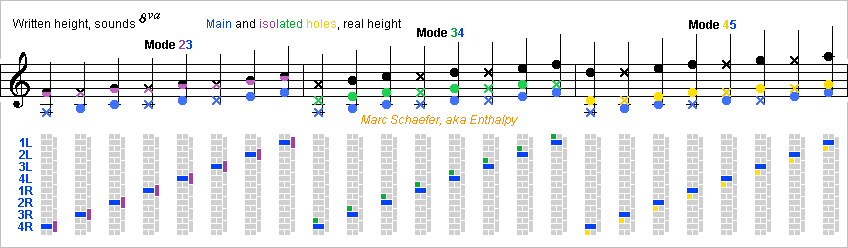

This soprito system F makes near-automatic cross-fingerings. The very high instrument resonates a soprano-long air column on modes 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9 and 12. One upper finger at a time presses the keys, like playing one note on a piano. Trills with the pinkie (needed only at the lowest note) and between the hands need more training, but fingerings are equally easy for all tonalities, the highest notes too. In each mode, the eight upper fingers produce one semitone each by pressing one main hole button. Some trills jump across the modes. Around each main hole button, more buttons open additional isolated holes to impose and ease the higher modes. Adjacent semitones share most of these buttons. The musician presses with a single finger a main hole button and optional isolated hole button(s) to create the pattern of open and closed holes. The three lowest main hole covers are open at rest, as seen on the lower figure, and connected so 3R closes two covers and 4R three. The dummy main button for 1R moves no cover. The four highest main hole covers are closed at rest and connected so 3L opens two covers, 2L three and 1L four. Consider the mechanism I proposed on Jul 02, 2017 scienceforums The spring force must be minimized. The covers are small. Five buttons surround each main hole button to open isolated hole covers some distance higher than the main hole: 2 semitones = major second, defining the mode ratio 8/9. 3 = minor third, 5/6. 4 = major third, 4/5. 5 = fourth, 3/4. 7 = fifth, 2/3. Adjacent main holes and buttons making notes a semitone apart, the isolated hole 3 semitones higher than a main hole is also 2 semitones higher than the next higher main hole, so the same isolated hole and corresponding button serve for both combinations: ratio 5/6 at one main hole button and 8/9 at the next one. Similarly, an isolated hole 5 semitones higher and its button for ratio 3/4 serve also 4 semitones higher than the next higher main hole, for ratio 4/5. The buttons for the isolated holes 7 semitones higher serve for only one main hole button each, but they can be combined with other buttons. The lucky combination mimics cross-fingering for modes 2-3, 3-4, 4-5, 4-5-6, 6-8-9 and 8-9-10-12. The mode 6-8-9 reaches already a transposed G higher than a piccolo oboe, a piccolo clarinet or Eppelsheim's soprillo. Whether the available mode 8-9-10-12, as high as the piccolo flute, can be played? The specialized narrow bore and the many open isolated holes help. The heights in this text and drawings hold for an instrument transposing in C one octave higher, while a tárogató or soprillo would be in B flat. A single set of 13 isolated holes serves for all mode ratios. Each hole cover has one key with up to 3 buttons, all moving together. At different locations, the 3 buttons make the varied intervals with the nearby main hole buttons: 2 and 3 semitones, respectively 4 and 5, respectively 7. The isolated holes are better distinct from the main holes. They spoil the unwanted modes better if they're smaller, and their positions adjust the intonation independently. The set of isolated holes overlaps the main holes and can reside on an offset line. A drawing may come some day. Single reeds need register keys, these help double reeds too. Each key could select one mode, with tolerance for trills. Covering only a sixth, the holes can be efficient, even be multiple at different near-nodes. I'd double the buttons at the left and right thumbs, 6+6 pieces if mode 2 needs no hole. The keyworks are simpler than an oboe or saxophone. ========== For softer sound, the main holes shouldn't be too wide, especially with a double reed. This offsets their position, and also the distance to the isolated holes. The isolated holes too can have the chambers against the strident frequencies I explained there scienceforums ========== The instrument has 8 pedal notes an octave below the mode 2. 4 extra holes and keys, for instance at the proximal phalanges or the left fingers, or at the thumbs, would reach them continuously. Though, I don't expect 4 octaves range from a soprito, and would not let a wider bore waste the high notes for low notes that a soprano makes better. Or should the instrument be twice as short, like the soprillo, use its pedal notes and the 4 extra holes, and stop at modes less high? The mode 4-5, with fewer buttons, would already give nearly the soprillo's range. Isolated holes closer to the reed should ease the emission. But with the long column and high modes, I hope to soften the sound and stabilize the intonation. Can instruments less high use this system? The keyworks make several joints difficult, and a soprano would be as long as a tenor, not good optically neither. Folded in three like a trumpet? Can a bassoon of normal length use the pedal notes and for the high notes the present easier fingerings? Assembly seems difficult then, while my alternative system there scienceforums has good joint lengths, simple keys and half-way decent fingerings. A high clarinet is less simple. The widely spaced modes need 9 or rather 10 main holes. The mode 3 an octave higher than a soprano needs a body as long as an alto. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

I suggested to replace Picea abies (spruce) with lighter Paulownia tomentosa (kiri) at the table of bowed instruments too, here on March 05, 2019 Koto luthiers reportedly don't get their Paulownia tomentosa from a company that selects the trees and quarter-saws them. They season the pieces in 2 years and carve plates along the L and T directions. Though, the length-to-width ratio of the violin family fits the L and R directions from quarter cuts. To balance the instrument, the back should be lightened too. Presently of Acer pseudoplatanus (sycamore), it sounds less strongly than the table if I read properly violin frequency responses, so it would need a bigger change than the table. Replacing Acer pseudoplatanus with Picea abies at the back would change more than Paulownia tomentosa does at the table. For instance some Pinus have intermediate properties, but they are not available in music instrument quality. Thinner Acer pseudoplatanus can be stiffened by a bass bar or bracings that pass under the sound post. The replacements must keep the resonant frequencies, not the thicknesses nor the mass. The frequencies depend on EL and on ER, not so simple. Maybe two different thickness ratios can be computed, from the ratios in EL, ER and rho between the materials, and some mean value used for a first prototype. The bass bar should change like the table; bending it would matter more with Paulownia tomentosa. The width could be kept and the height scaled like the table thickness. The anisotropic stiffnesses act differently on the bass bar, so the height needs further tuning. Replacing only the table and bass bar in a first prototype would already tell the effect and whether the back needs improvement too. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

RSP Technology uses rapid solidification and sintering to produce alloys with unusual compositions and properties. They have improved and widened their product sprectrum Precision equipment at RSP Technology A frame with 11.6ppm/K from their RSA-453 (Al-Si50) would match carbon steel strings perfectly, better than cast iron does. E=110GPa for 2500kg/m3 are 1.67* better than steel and cast iron, as good as TiAl, wow. Many hypothetical string materials need nearly the same frame expansion as carbon steel: Maraging, martensitic stainless (optionally with precipitation hardening). Strings of CoCr20Ni16Mo7, Duplex stainless or nickel superalloys would be stabilized by 13.6ppm/K from the RSA-443 (Al-Si40) and RSA-441. Strings of austenitic stainless (optionally with precipitation hardening) would be stabilized by 17.3ppm/K from the RSA-4019 (Al-Si20 etc) and RSA-461. The elongation at break is worse than brass. The parts I made of RSA-708 didn't break by falling on the floor and could withstand significant deformation by hammer. Last time my employer needed an ultra-strong rod from RSP, he just paid and got it. Some 30€/kg are a hurdle for music instruments. I haven't seen tubes nor exotic profiles from them, so a frame should use rods, or waste costly material, or convince RSP to experiment. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Bore width of wind instruments

In the first message, the link to (previously Dartigalongue) Sophie Dervaux playing Saint-Saëns' sonata is broken, but here's an other record: i0M1AIDLX8Y at 39:50 the very caring pianist let the bassoon play at a reasonable volume hence with a softer sound. The difference with the narrower French bassoon played by Julien Hardy remains.

-

String Instruments

Elements for the soundbox of the grand cimbalom suggested here on August 25, 2019. Modelled as 1.2m*0.55m, the soundboard is a quarter-wave broad of the lowest C=65.7Hz, so piston move would give it 5.6mohm*F2 = 24ohm radiation resistance and 1m/s rms (arbitrary for comparisons) would displace 0.66m3/s rms and radiate 10W. 0.15m depth provide 0.10m3 and 0.61µF or j0.25mS at 65.7Hz. The same 0.66m3/s create 2.6kPa in the box whose 1.9m2 dissipate 6*10-9*SP2F0.5 = 0.63W by conduction, far smaller than the radiation. Conduction losses would accept a shallower box even at this bass. The unstressed soundboard of Picea abies (Norway spruce) weighs some 3.5kg with bracings, bridges and strings: the 0.66m2 piston has 8H inductance. The Helmholtz resonance can be at F#=93Hz where soundholes add 12H, tiny margin. For the resonance, the soundbox could be slightly shallower, like 0.1m over the musician's legs, with a thicker opposite face, where the table is higher. The metal frame being outside, only the soundholes vent the box. 338 holes, D=1mm h=2mm, achieve L=12H R=0.64kohm so Q=27 from these losses. Other figures can tune the resonant frequency and amplitude to please the ear. The holes can make up one or several rosaces, for instance facing the public. The spreadsheet evaluates resonant frequencies for a 1.2m*0.55m ribbed table of Picea abies held flexibly at all edges. CimbalomBracings.xls Tuned arbitrarily for 140Hz, then about a fifth between the low resonances. The ribbed table weighs 3.3kg/m2 and outpaces sound in air above ~500Hz. Paulownia tomentosa should enlight the table, and varied rib height spread the resonances better. Soundposts could vibrate the back plate too to provide interleaved resonances. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Fingerings

If an instrument with my even fingerings has the thumb platters on a straight joint, a common tilted axis can still vary the lift of the platters according to the note height. As my even fingerings let all notes open all platters below the main transition, the platter lift can vary smoothly with the note height.

-

Woodwind Fingerings

All bow joint covers move by the same angle as they are one single axle and synchronized, in the design I proposed on Sep 16, 2018 - Sep 23, 2018 - Sep 26, 2019 12:06 AM Wind instruments benefit from wide bows, so two holes there are nearer to the axis, and their covers lift less. Besides choosing the bow radius, which the narrow bore of the oboe and bassoon families ease, these two holes can be put more outwards than the bore's middle line, and all other holes more inwards, to minimize the difference. The hole diameter can also compensate the lift height somewhat. Covers for lower notes must lift higher. Offsetting the axle closer to the higher branch does that, tilting it closer to the higher notes too. The chimney rims need not be parallel to the bow plane. Pads work better if the rim is rather perpendicular to the movement. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Fingerings

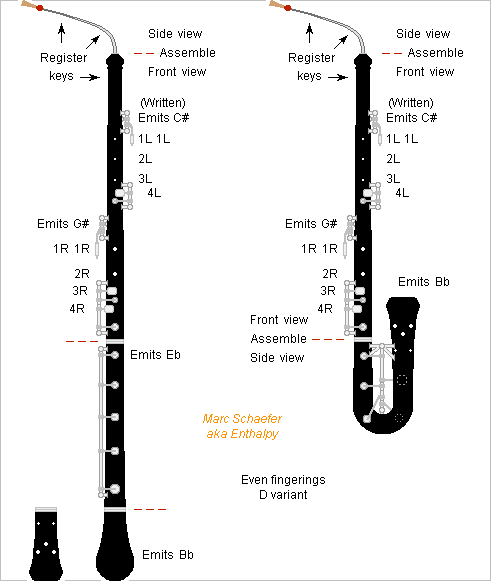

The D variant of my oboe even fingerings makes a sleek cor anglais, simpler than a baritone oboe, almost as simple as a soprano oboe, as holes spacing decides it. I don't display the thumb pushers nor the register keys. After hearing the effect of Pmma, the materials clearly matter at an oboe, and I would shun brass and nickel silver for the bow, the bell or pear and maybe the bocal, but would consider lossy alloys that can be electroformed: NiCo, Pcm, sterling silver, said to improve bassoon bocals. scienceforums and around Some polymers might improve the body: damping polyketones, and stiff and damping liquid crystal polymers, possibly with graphite choppers or filaments. They might outperform Dalbergia and they can cross borders. Better, they avoid the plastic lining in the oboe or bassoon bore. Silver tenons are said to improve wooden flutes. I've proposed a model that speaks against cork, there scienceforums illustrated by a clarinet, but this would apply to all double reeds too, including at the bocal. I've drawn a low Bb because the oboe has it. Stowasser's bell with many small holes shall even out the emission and timbre bette than the pear shape. All cor anglais should have this alternative, maybe an addition to existing instruments. I suppose Stowasser's holes could replace everything Heckel added to the pear of his heckelphone. Lupophone? Bending the low joint would shrink a cor anglais to an alto saxophone's size. Electroforming seems easiest if some alloy dampens enough. I've suggested processes to make bows of wood or polymer, or to obtain them by filament winding Aug 16, 2019 04:16 PM - Dec 04, 2018 - Mar 30, 2019 02:34 PM and around I've shown from the side the stiff pyramids that connect both branches of the bow and the keys' axis for reliable keyworks and hopefully better sound. See also the baritone oboe. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

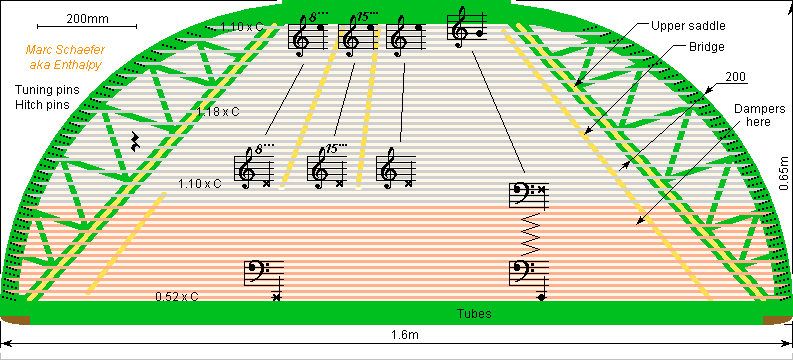

After all, here's a grand cimbalom with my octave tuning and a metal frame outside the soundbox. It may be easier to learn and adds a high fifth of dubious quality to E=2649Hz, as high as some hammered dulcimers reach, within the piano's bad last octave. 46 choirs spaced by 12mm give the usual length, and the sections overlap by 2 semitones; if playable, less spacing would stiffen the frame. String velocity between 1.10*C and 1.18*C, dropping to 0.52*C at low notes, keep the frame 1.6m wide, but if playable, longer strings sound better. The string chart shares the low notes with existing big cimbaloms. The Hackbrett of July 23, 2019 here could make a tiny change and share exactly this grand cimbalom's string chart, but for low strings. The pinblocks are but longer than on August 12, 2019 here, but they keep the 1.0 semitone flexural stiffness thanks to their arch design, here of maximum width. The skewed struts are 10mm wide, the arc 38mm and the chord 30mm, with 166mm midwidth height, all 15mm thick. The tubes stay as before. Torsion is less bad as I evaluated here on August 12, 2019 as the skewed struts improve that. Strings reduce the mutual detuning by pulling at the arcs, but I did NOT check all buckling risks. This construction enables a bigger soundboard that breathes better. The soundboard and box can stop before the pinblocks for easier use, at my previous designs too. Something at the pinblocks' edge should catch broken strings. The pair of arched constructions weigh 16.8kg of duplex, gained 2kg, but cost 40kg if cut from a 15mm sheet. Carbon steel would be cheaper, and casting even cheaper, of duplex or cast iron. TiAl would save 1/3 mass, metal matrix aluminium about as much. Making the arch of tube seems complicated. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Fingerings

Thanks for your interest! Yes, I like jazz, though I started the alto sax for classical music, after hearing it at the pictures at an exhibition. I have a record of Take five with Gerry Mulligan at the baritone, very nice sound. Any woodwind is easier than the flute, and by much. The sax has easy fingerings but has less known shortcomings. Very high in demand are the oboe (needs only a huge pressure and extra-strong lips), the bassoon (rather easy, especially as compared with the flute), the bass clarinet (works very well, easier than the soprano, have your own and orchestras seek you already).

-

Woodwind Fingerings

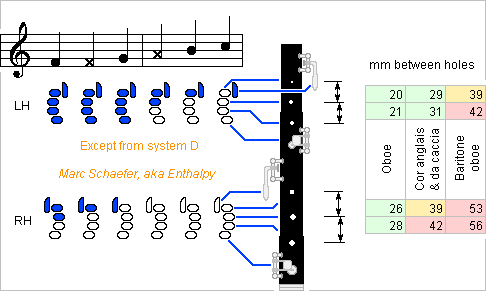

Among my proposals for the oboe and similar, the D even fingering variant takes the fewest and simplest keys. How many bare holes can it use? None at the five thumb holes. Not at the second index hole that should be placed properly a semitone higher than the first. Supposedly not at the pinkies as they are short. 6 holes remain. They can all be bare at the oboe and oboe d'amore, for agile, silent, reliable, light and cheap instruments. At the oboe da caccia and cor anglais, the left hand holes can be bare, plus two at right hand: same R1 to R2 spacing as on the bassoon, comfortable but for children. The baritone oboe can have two bare holes at left hand. The real distances will be slightly smaller. The table takes half-wavelengths in air, but small tone holes are higher on the air column. I would not have long skewed tone holes as the bassoon has. They behave differently at the upper register, but the cross-fingerings there should fit a whole instrument family. Chambers eccentric above the tone hole narrow bore can gain a few mm. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Woodwind Materials

Following the message of Jan 15, 2018, here''s one more comparison between grenadilla and Pmma oboes, both from Marigaux and played by the same musician, in the same bad room full of echo: rBEysvPiYPY at 0:34 and 1:38 and I hear exactly the same difference as with the other oboist: Pmma sounds like a piece of plastic, especially at the low notes. Simply the wrong material for a woodwind. It's even surprising that the difference is so strong and repeatable. Possibly the oboe depends more on the walls materials than other woodwinds.

-

Woodwind Materials

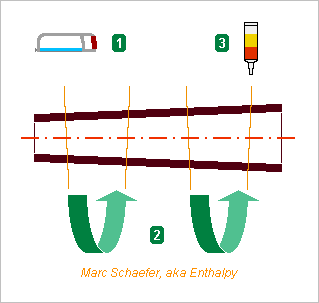

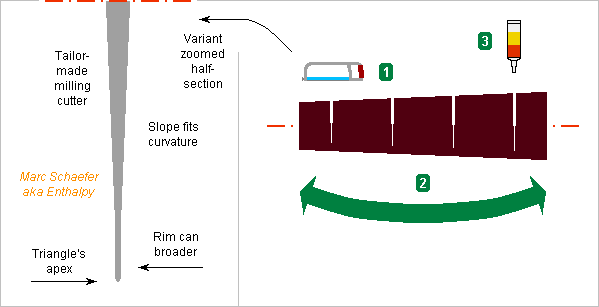

According to Cary Karp, who studied two remaining oboe da caccia made by Eichentopf jstor.org - wikipedia the body was first machined straight, then (gashes) kerfs were sawed at the rear side, the remaining wood bent over steam, a slat glued at the rear, and voids filled. Playing copies were made in recent times the luthiers know the missing process steps. My tiny contribution: let make a cutter to mill the gashes accurately. It can have precisely the needed shape, except for the rim that needs a minimum width. The conical shape demands cutting edges as far from the rim as the gashes are deep, and the cutter's radius can exceed this much. Several cutters on a shaft can work more quickly. ========== I've already suggested to cut wedged body segments completely from an other and glue them together as a curve scienceforums and here's an illustration: Slats can usefully hold the segments precisely in place while glueing, especially if they press against accurate flat surfaces made at the body before segmenting. ========== Both processes apply to polymers too, including polyketones and liquid crystal polymers, except that heat rather than steam softens them. I had already suggested electrodeposition Jan 01, 2018 - May 02, 2018 and filament winding Nov 01, 2017 to produce curved body parts. The two present processes need a different know-how, possibly more accessible to pure woodwind luthiers. Good glue joint aren't easy on polymers. Glueing POM is known. Solvents can prepare a surface for glueing or make the joint Few solvents are known for polyketones: hexafluoroisopropanol, meta-cresol, and the more benign solutions of ZnCl2, ZnBr2, ZnI2, LiBr, LiI, LiSCN that leave residues. Solvents for liquid crystal polymers are uneasy too: pentafluorophenol, trifluoroacetic acid. Though, slats alone won't bring much stiffness not toughness. Welding polymers is better than glueing them when possible. Many woodwinds need or would benefit from curved body parts of wood or polymer: alto and lower clarinets, bassoon and contrabassoon, baritone oboe, alto and lower tárogatók. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

All piano soundboards I've seen have the plate's fibres in one direction and bracings in the cross direction, where the plate alone would be too flexible. The spreadsheet HackbrettBracings.xls from July 28, 2019 in this thread claims that a thinner plate, and bracings in both directions, would be much lighter at identical resonant frequencies. The instrument would then be louder. This needs tall narrow ribs that keep stiff where they cross, not trivial. Cimbalom Vsiansky do it, with shallow wide ribs cimbaly.cz and some guitar luthiers too. Maybe one direction can be above the plate and the other below. This should combine with the use of kiri, Paulownia tomentosa. Unless the balsa sandwich of August 03, 2019 03:45 PM is better. It's not the lightest, and I doubt about its damping, but it looks easier to build. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

String Instruments

Positioning the big tube higher at the metal frame suggested for cimbaloms, Hackbrett and similar is advantageous. Both tubes experience a force less amplified, and their deformations act less amplified on the strings. At least the distal tube can be level with the mean string height. Then the small tube feels no force and contributes no string deformation - it can be lighter, maybe suppressed. As compared with tubes 30mm and 180mm below the strings, the big tube's elasticity acts (5/6)2* as much on the strings, so it detunes by 0.7 semitone instead of 1.0, or it can be lighter, and the small tube doesn't add 0.1 semitone. How high can the proximal big tube be, ideally level? Alas, I don't play these instruments. The mallets strike the strings head down, but I ignore by how much. The strings are also higher than the average where striked. So a D=48.26mm tube doesn't have to be 30mm below the strings.