Everything posted by joigus

-

Is there magnetic moment of hydrogen atom that is not equal to Bohr's magneton?

Any conserved quantities are just conserved quantities. After you find out they're conserved, you can look upon these quantities as defined by local densities for them: local density of energy, angular momentum, and so on. But once you mathematically integrate over all values of space, they're just what we call a quantum number. The quantum number is neither here, nor there, but an overall property of the state. Same goes for non-conserved quantities that are nevertheless defined by local densities. Example: expected value of position. Only, we don't call them quantum numbers.

-

quantum determination question

You're confusing correlation with causation. That's not what I'm saying. The experimenter's minds are determined by a common cause, either in the past --exactly as in the singlet state-- or not. Only state of affairs is more complicate in the case of the singlet. Confusing of correlation with causation can be very, very misleading. Sometimes, not even causal connection in the past can be significantly attributed. For causation to be attributed, you must have a theory for the common cause.

-

I could not reach Scienceforums for 3 days

That was my best guess after doing a whois search from Linux command line. +1

-

Is there magnetic moment of hydrogen atom that is not equal to Bohr's magneton?

🤣🤣🤣 Well, they say "often." So often but not here. They want to keep their readers on their toes.

-

Is there magnetic moment of hydrogen atom that is not equal to Bohr's magneton?

Yes. A classic one: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lamb_shift Bohr's magneton is the magnetic moment due to orbital motion. That's all it is. The magnetic moment of the electron's spin is expected to be about that when looking at Dirac's equation as if it were a one-particle equation, but it happens to be different. The difference is due to radiative corrections (contributions of virtual particles.) This displaces the values of all physical constants from their quasi-classical value (often called "tree level") to a different value. I'm not sure what you mean, but the g-factor or gyromagnetic ratio (a factor that essentially tells you how much it deviates from a Bohr magneton) of nuclei is all over the place: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuclear_magnetic_moment#g-factors Because nuclei are composite objects, I'm sure a lot of the variation has to do with nucleon-nucleon interactions calculable in approximate models, even before you get to radiative corrections. Elementary particles have considerable variance in their magnetic moments too: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magnetic_moment#Elementary_particles

-

Musing about QM

Photons are not valid frames of reference. You can watch photons do their thing from outside, but you cannot sit on a photon and watch the world from the photon. Einstein considered this just as a gedaken experiment. This is because from the POV of a photon --to the extent that it makes any sense at all-- the world is frozen in one instant of time. Photons are useful thingummyjigs in order to parametrise other things going on, but not useful to parametrise their own view. They have no view. You're getting into the quicksands of quantum gravity here. I'd rather not take that pill just yet.

-

quantum determination question

I'm afraid Mr. Juan Yin --and yourself-- are gonna have to do better than that. If I ask two students, one in Shanghai, and another in Massachusetts --at the same time in a given inertial reference frame-- at which speed the Pythagorean theorem is verified, they will find the speed is infinite. How could that be?: Because the truth of the theorem was already encapsulated in their respective minds long before they performed the measurement. What you say only proves there are people in Shanghai wasting millions of Yuan in measuring very stupid things. It's happened before.

-

crowded quantum information

EPR is not an effect, nor is it a "theory" as you say further below this quoted piece of text. EPR is a theoretical argument presented as a contingency: If this (what I propose here) is true, then that (what you've been saying) must be false. If what you've been saying is true (in the face of this example), then something we know for sure (relativistic causality) would have to be false. It's a bit involved, granted. But no "effect" is proposed, and no "theory." And it is a very crude argument in its original form, although it's very astute. The EPR argument, in its original form, is quite flawed. I've tried to explain why somewhere else: https://www.scienceforums.net/topic/127991-an-analogy-for-superposition/#comment-1219399 Nobody said "nothing unusual," and certainly nobody said "nothing non-classical." It's completely non-classical. It's quantum mechanics! ACZ and others performed experiments which bring out the flavour of quantum mechanics at its most strange and counter-intuitive: This fundamental non-reality can be transported at a distance. For one thing, they proved quantum mechanics to be right. For another thing, they managed to keep quantum coherence for very long distances. The last one in particular is a monumental technological achievement. This could be very useful for quantum computing. I'm thinking, eg, that you could delay the decision of defining a qubit until some ancillary calculation is completed. You could decide to set your qubit to a totally random couple of qbit states. It gives you handlers for your qubit logical gates (the AND, the NOT, the OR, the CNOT...). When you transport qubits instead of bits, there's a phenomenally richer set of possibilities. You would have to ask an expert in quantum computing to learn more. But you could do many things with those gates that would be impossible with classical gates.

-

An analogy for superposition

Exactly. |state of the cat> = (1/sqrt(2))|cat dead>+(1/sqrt(2))|cat alive> These numbers 1/sqrt(2) are called probability amplitudes, and their squares 1/2, 1/2 are the probabilities. I don't want anybody to run away with any hurried conclusions, but the truth is the best analogy for these quantum superpositions is perhaps the human mind itself: When you're not sure about something, it's neither here nor there. It's only when you learn what happened that your mind gets either here or there. In the meantime, there's this Schrödinger equation, which is like the indefinite mind rotating between one and the other. When you measure, the state vector stops on one of the axis. Now, this stopping on one of the axis is called the projection postulate, and is known to be incompatible with the Schrödinger equation.

-

An analogy for superposition

Sorry, the words "composite system" were not essential. This "ghostly presence" happens in a simple system too. What I meant by "composite" is 2-particle, 3-particle systems, etc. Anti-properties is not the key. That's just for spin because for every possible value of it you have the corresponding negative value. It's just two or more values of the same property. Take the example of benzene. The molecular orbitals of the double bonds are not in a definite position. That's what I meant.

-

An analogy for superposition

I would try not to overthink it, as it's an analogy after all. As Swansont said, in the end there's no information that can tell you how it's going to end up, really, only the odds.

-

An analogy for superposition

It's taken from Swansont's toolkit. I liked it too. I've just added a couple of pictorial features. I'd rather you included dissipative forces coming into play, and that's because they replicate this "effective loss of unitarity." But what happens when the environment selects a particular projection, how the environment selects that particular projection? In still other words: What physical variable tells Nature "this is what happens," and "not the other," and effectively interrupts the causal and reversible course of Schrödinger's equation, that's up for grabs: Many universes... meh! Empty waves... mmm --this is the one I like more. TIQM... eew! Superdeterminism... eeeeew!!! ... You can say --semantically totally equivalent to the former-- the measured component becomes "green," and we can only see "green" things. The non-measured components become schmancy, and we can only see non-schmancy things. An angel told me this is the one and only etc.

-

An analogy for superposition

The EPR argument is really a bit complicated historically. Einstein did not think of entanglement right away when he co-authored that paper. He was more concerned about completeness at that point in history. Schematically, he said: If I can predict with 100% accuracy the result of an experiment without actually measuring it, there is a something, there is a presence, there is a variable, real as can be, (a value of momentum in his case; he very shrewdly used a conserved quantity of which no exception is known) which must somehow be there. Therefore, your theory (quantum mechanics) must be incomplete. If your quantum mechanics purports to insist on incompatibility of certain variables, your quantum state must be updated by means of an outrageous violation of relativistic causality. There's no other way. In other words: He was pushing QM's completeness claims against relativistic causality --a principle that he knew better than any other was "sacred"--. Both of them, completenes of QM, and relativistic causality, cannot hold at the same time. It's one or the other. But he (and Rosen, and Podolski) missed a couple of tricks. 1) You cannot prepare a bipartite quantum state in which the momentum is zero in the CoM system with total accuracy. So momentum is actually always indefinite. 2) The state is actually entangled: (momentum p)particle 1(position x)particle 2-(momentum -p)particle 1(position -x)particle 2. Here, David Bohm enters the story. He took the whole discussion to the case of spin. Why? Because angular momentum is exactly conserved, but for angular momentum (spin is a particular case) you can actually prepare states that are totally indefinite in each variable, while completely definite for the sum of both. Then you can do the correlation analysis very cleanly, and reasonably clearly. Then comes John Bell, and for some unfathomable reason --IMO-- rescues a word from Einstein's old toolbox that had better been left out, because --again, IMO-- plays no actual role in the argument, except indirectly. Namely: "locality." In fact, if you go over Bell's papers on the subject, and its antecessors: V. Neumann, Gleason, Jauch and Piron, etc., and its sequel: Clauser, Greenberger, Horne, Zeilinger; the position of the particle plays no role in the theorems. It's not even mentioned in the axioms. It's only there because these great physicists mention it over and over. Why? Because Einstein mentioned it in his original argument. And they have deep respect for Einstein. And they don't want to be wrong. They all knew in their heart of hearts they were doing a theorem about realism, but didn't want to drop this word "locality," --IMO-- only just in case they missed something essential. But all those theorems about "local realism" were actually theorems about "realism." If I disprove local realism, it's just as good to disprove realism. If there isn't any realism, there certainly won't be any local realism. Imagine a modification of reality as we know it by means of some kind of "ghostly presence" of every which property of a composite system. A glove can be black and not black at the same time, a glove can be left-handed and right-handed at the same time. Etc. But in such a way that the "potential right-handedness" is equally likely than the "potential left-handedness," and so on. But the total handedness is zero exactly, the total color is grey = black + white exactly, etc. Holding these two experimental truths in your mind is what's very, very hard. When you measure, the system filters, selects, shows, highlights... whatever you have decided to see, and it shows the correlations that were there all along. You select a "component of reality" and bring it onto reality. Something like that, for lack of better words. Does that help at all?

-

An analogy for superposition

I like this analogy better: A coin tumbling and wobbling with no significant amount of dissipation of energy would be the equivalent to a quantum state being in a superposition and "rotating" according to the Schrödinger equation. Not heads, nor tails. Not yet. At some point, the dissipation comes into play --equivalent to the projection postulate = measurement = formal violation of unitarity-- and the coin has to "decide" whether it's heads or tails. The problem I see with your analogy, which is otherwise as valid as any other --with the natural limitations that no classical logic can totally reproduce the quantum-- is that it assumes the "observer effect." The result is brought about by the act of measurement (different people seeing different things, as they measure.) There are many things I like about this example of the wobbling coin.

-

crowded quantum information

LOL. I'm passionate about arguing, and I can't hide the fact that I'm loving this particular debate. But in the end it's about learning, not about winning. I've tested your patience in the past, haven't I? I learnt a very important observation back then from our debate on free will. Namely: The fact that a property is emergent doesn't make it any-the-less factual, any-the-less consequential. It was so important to learn that I may have missed other, more subtle points you were making. But I'm thankful for having learnt something from that debate. If the landscape of ideas eventually gets cleared up in this debate, then perhaps we will be able to tackle the "crowding of information" that @hoola was talking about, with interesting advances like, eg, https://phys.org/news/2021-08-critical-advance-quantum.html Which go right to the heart of the matter as per OP question. The crowding of millions of qbits. Or perhaps we will be able to discuss what happens to the wave function when measurements are performed, or whether the state vector is a figment of our imagination or not. Or whether we should consider the quantum phase as a placeholder for beables. Or...

-

crowded quantum information

The properties of the entangled particles are established from the start. When a neutral pion decays into two photons, all the correlations are there from the start. Both measurements are random. But any observer that has access to both results, once information from both Alice and Bob is gathered and "centralised" --and therefore the criterion for FTL or not FTL will long have been outdated-- will discover eventually that the results were anti-correlated, if they happened to measure the same projection of spin. And they will be totally non-correlated, if they happened to measure different projections of spin. The tenses in "will" and "were" are essential here. At the moment they measure spin, either Alice or Bob, they write down the result, but they have no way to know whether: 1) The other one measured the same projection of spin, and their result is anti-correlated with theirs. or, 2) The other one measured another projection of spin, and their result is totally non-correlated with theirs. I told you, it's like a house of cards. If you drop randomness but keep quantum superpositions, sending FTL signals would become possible. That doesn't happen. If you drop quantum superpositions and non-commutativity, it becomes like a pair of gloves dice that are totally correlated (or anticorrelated, as the case might be) for every observable. It's random, totally, unmistakably. And it's superpositions (no internal reality.) It's impossible to explain this to you with firecrackers, boots, dice, or little leprechauns that take decisions. Firecrackers don't have internal non-commuting variables. There is a fathomless void, and impossibility, an insurmountable logical obstruction here in the space of classical analogies. There are no classical analogies. Local, totally. But random, not because, but because: No. No internal mechanism, no manufacturing differences, no internal switches. Nothing. Niente. Nada. Nichts. Zilch. Quantum mechanics! Quantum mechanics! Quantum mechanics! Oh, no matter, you can say that they broke me. I was playing this ping-pong match Nadal style, until I finally went all Djokovic on Bangstrom. It's not a totally bad analogy. But all our classical analogies are doomed in the end, because classical tethers cannot reproduce non-commutativity: Say, eg, in the case of the astronauts, (nationality)x(handedness)-(handedness)x(nationality) = i x (gender) What the hell does that mean in terms of tethers, coins or dice? Systems that behave this "crazy" deserve the name of "quantum." The intermediate tether holds the anti-correlation, but in such a way that, while it's evolving, following the Schrödinger equation, it cannot be said --without falling into inconsistencies-- that the astronauts are this or not this, that or not that. They are in a quantum superposition of all the "this" and "not this" possible questions. Being American or not, lefty or not, woman or not, equally likely. When you put two astronauts inside respective space pods, you want to believe they either are American or not American, lefty or not lefty, and a woman or not a woman. You want to believe, eg, the American is, say, left-handed, and a woman. She must have been!! She was all that from the get go!! Then the other one is not American, right-handed, and a man. You want to believe that, naturally! Why, they are real astronauts, right? If the American is a woman, she must have been a woman all along. If she's right handed, she must have been RH all along, etc. That's what doesn't work with quantum systems. The system "selects" the pairing of results --corresponding to one property-- only after you perform your measurement, and not before. And I say "pairings of results" knowing full well what I mean. According to QM, if I want to know if the astronaut is a woman, I must give up knowing whether she's LH or RH, or her nationality. The reason is they are incompatible properties. If you "measure" the gender, one space pod has a woman in it, and the other has a man. If you measure the nationality, one space pod has an American, the other not. What if you "measure" the handedness in one and the gender in another? Then anything's possible. You sometimes get a lefty here and a woman there, a right-handed here and a woman there, etc. All combinations equally likely. It is an intimate connection between the astronauts, much more intimate than you could get with any classical bipartite system. It's as if they both were just one thing, and you could only look at each of the "parts" through one filter: nationality, or handedness, or gender. You must decide which one. I don't know how to package that into a single analogy. The best I can do is: Try to picture a reason why, if you want to know my gender, you absolutely cannot say anything about my handedness, or my nationality. In fact, if I'm a man, I'm absolutely neither right-handed, nor left-handed, neither American, nor not American. This is as weird as can be, but not because of non-locality. It's because of non-realism. Because gloves, and dice, and coins are real --whatever that means--, they hold all their meaningful properties at once --yeah, that's what it means!!--, they can't illustrate anything deep about QM one hundred per cent. Little leprechauns that take decisions would actually be possible to accomodate to superdeterminism.

-

crowded quantum information

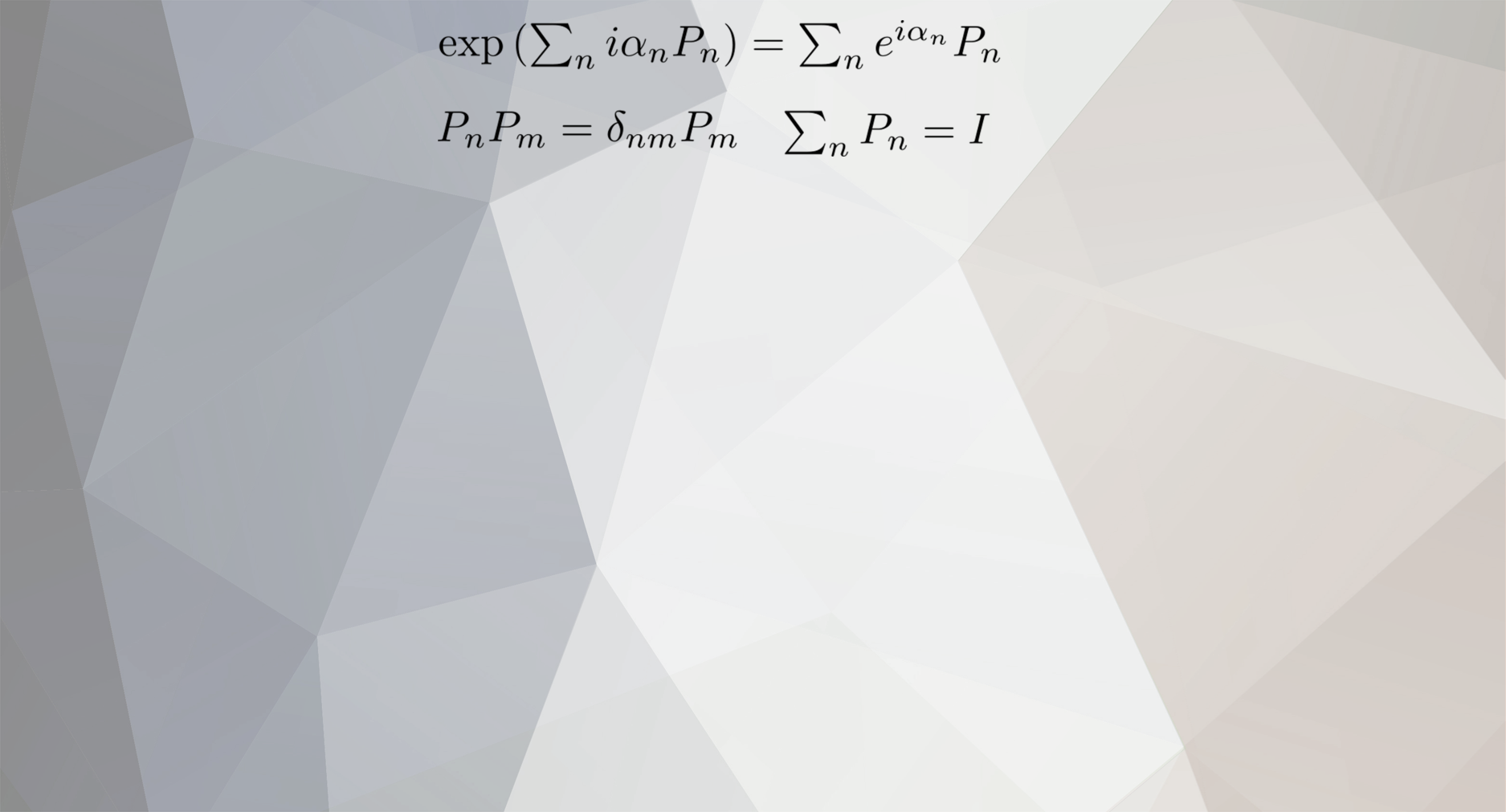

Some cleaning up of silliness seems necessary. I can't let this go. I don't know who said it, but it's sooo foolish... Bell's inequality is certainly not the weirdest theorem in the world. It represents the common world. The world of "yes" and "no." I'm not responsible for stupidity propagating around, nor is @Eise, nor is @MigL, nor is @swansont, nor is @Ghideon. Bell's theorem is about classical propositions. How could it be "weird"? What's "weird" is, perhaps, its violation. A = My cat is alive Not A = My cat is not alive B = My sweetheart is happy Not B = My sweetheart is not happy C = the kid is a girl Not C = the kid is not a girl Probability(A, not B)+Probability(B, not C) is greater or equal than Probability(A, not C) The CSHS inequalities are are more suitable version for experimental verification. Thanks to @Ghideon. +1 How is that strange? It's far from obvious, but not strange at all. What's strange is that (colour for dramatic effect), Quantum mechanical probabilities violate this!!! This is because, for quantum mechanics: Probability(Sx=up,S45º=down)+Probability(S45º=up,Sy=down) is less than Probability(Sx=up,Sy=down) And how could that be? Only because a premise of the theorem is wrong. Which one? The assumption that variables are either this or not this. (The assumption of realism.) The premises of the theorem are so weakly-assuming that there is no other option. IOW, there's barely any other premise. It even includes as a possibility statistical dependence: A totally contained in not B, etc. Because quantum mechanics allows for states for which my cat is neither alive nor dead, etc, with a probability amplitude that the cat is 1/sqrt(2) alive and 1/sqrt(2) dead, QM violates the otherwise simplemindedly-true, but devilishly astute, theorem due to Bell. And that's almost all there is to it. What are classical data? What happens when my sweetheart is definitely not happy? That's another matter. Does decoherence arise "instantaneously"? (whatever that means.) That's another matter too.

-

crowded quantum information

Jawohl! Es macht sinn!

-

crowded quantum information

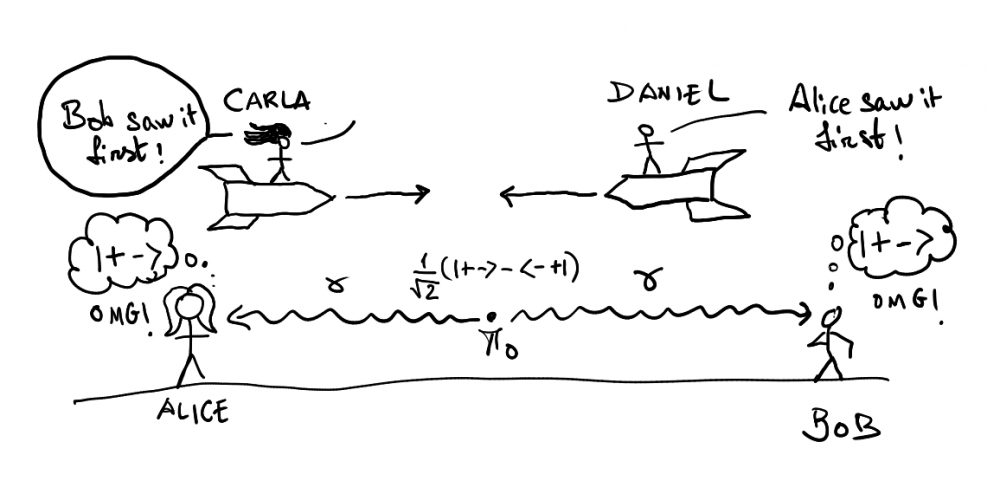

No!!! Is there any single statement about this that you can get right? Alice and Bob are sitting in the same reference frame. They can use laser to determine they saw it at the same time. They determine they saw it at the same time!!! (In their common inertial reference frame.) Carla and Daniel, on the other hand, equipped with lasers too, are sitting each one on yet two more inertial reference systems. They infer different coordinates for the reception. From the POV of Carla, Bob's photon reaches Bob before Alice's photon reaches Alice; from the POV of Daniel, Alice's photon reaches Alice before Bob's photon reaches Bob. Why do I think you don't understand? Because you don't. You simply don't understand it. You don't. You don't. You don't. You don't. You don't. You don't. You don't. You don't. You don't. You don't. You don't. You don't. You don't. You don't. You don't. You don't. You don't. You don't. You don't. You don't. Don't. Don't. Don't. Don't. Don't. Don't. Don't. Don't. Don't. Please do. Please do. Do. Do. Do. Do. Do. Do. Do. Do. Do. Do. Do. Do. Do. Do. Do. Do. Oh, please, do.

-

crowded quantum information

Nope! I think these comments get to the heart of the matter from a philosophical POV. My take on it is the wave function represents infinitely many occurrences we simply cannot tell apart from each other. IMO, up to a certain point, to the extent that the theory has been mathematically understood, choices may open up. Don't forget that, even when quantum mechanics has given you a valid choice for your \( \left|\psi\right\rangle \), there are infinitely many prescriptions equivalent to each other. Once we've written the state vector in the so-called position representation, \[ \left\langle \left.x\right|\psi\right\rangle =\psi\left(x\right) \] we can still change the prescription point-wise as long as there is a gauge field accompanying it, \[ \psi\left(x\right)\rightarrow e^{iq\theta\left(x\right)}\psi\left(x\right) \] \[ A^{\mu}\left(x\right)\rightarrow A^{\mu}\left(x\right)-\partial^{\mu}\theta\left(x\right) \] So right there gauge ambiguity is telling you your state object is very, very far away from being determined. If I had to bet, I'd say the "mysterious part" --the persistent thwarting of any attempts on our part to determine the system-- is hidden under the carpet of gauge ambiguity: From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Introduction_to_gauge_theory#Gauge_invariance:_the_results_of_the_experiments_are_independent_of_the_choice_of_the_gauge_for_the_potentials The spin factor of the state being even more deeply non-realist than the space-time part. IOW: Spin variables cannot even be represented by commuting variables.

-

Where Does Holy Water Come From?

In early Christianity the sharing of the food was the real deal, more similar to what you tell me about the Presbyterian church. From the point of view of healthy practices, holy water at the entrance of Catholic churches must bee teeming with bacteria. So ... eew. I don't think it's very sanitary. Anyway, trying to answer to the question of where it comes from, I've found this, From: https://www.stmarybasilicaarchives.org/archives-desk/history-and-usage-of-holy-water/ But given the role that water played in ancient Judaism, I think we shouldn't completely rule out the possibility that the origins of the practice go as far back as the Essenes, or perhaps earlier.

-

crowded quantum information

Instant in one reference frame is 1 to 2 in another, and 2 to 1 in yet another for space-like intervals. The order of events is frame-dependent. Please, oh please, do learn some special relativity. At least the basics. "Instant doesn't mean anything in special relativity. That's the point. (Ahem, ahem, sigh.)

-

Where Does Holy Water Come From?

As a person raised in the Catholic tradition, water was never very high on my agenda. The Church offers you as many servings of it as you want when you enter or leave their offices. What always kept me wondering was why wine was a privilege for the Father only, who did the consecration of bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ. You could have the (sorry excuse for) bread they give away, but never the wine. I've been blood-thirsty ever since. Red wine is a miracle.

-

Best resources for self-studying math from K-12?

Yes, but I should have read the post more carefully. I just hope new comments draw attention so that OP can get a proper answer. My idea of American education is that knowledge is more practical than in Spain. I've seen courses in Britain which, even on the theoretical side, go more from example to theoretical idea. I'm more familiar with Britain than America. We have six primary-education courses, then four secondary education courses, and then two pre-universitary courses we call "Bachillerato." I always say any person who would assimilate all the the Bachillerato courses (Science, Human Sciences, Social, and Arts) would --potentially-- be a modern Leonardo Da Vinci +. The unfortunate result is that most people don't get a proper education in any of them, probably due to excessive emphasis on theory, to the detriment of practical knowledge.)

-

Hypothesis about the formation of particles from fields

It was you who started talking about neutrinos. From a classical POV, neutrinos would have zero magnetic moment. Magnetic moment doesn't come from mass, but from circulating currents. In the context of the Standard Model, they're expected to have a very small magnetic moment, no doubt due to radiative corrections. AFAIK, only upper bounds to magnetic moment of neutrinos have been experimentally determined. It would be a good idea to read what I posted above.