Everything posted by joigus

-

Can a material object cross the event horizon of the Black Hole?

BH falling into object or the other way around is a matter of reference frame. The thing about small Schwarzschild radius --in comparison to falling object-- is a question about tidal forces (gradients of gradients or second-order derivatives.) When object is very close to centre of gravitational attraction, it's no longer possible to consider local inertial system as such, due to second-order effects (second order derivatives.) I'm sure you know about this --from what I can infer. You're either an expert on this or a person so knowledgeable that not even an expert could tell the difference.

-

Can a material object cross the event horizon of the Black Hole?

As usual, I refer to the question on the title when I can't follow the logic that comes below. Can a material object cross the horizon of the BH? If the Schwarzschild radius of the BH is much bigger than the size of the material object (2 cases, I'm assuming free fall): From the outside to the inside of the horizon: Yes, and if the BH is big enough, the material object would be none the wiser that it's crossing a horizon. From the inside to the outside of the horizon: No, and due to its being in free fall it would be none the wiser that a huge part of space-time is forbidden to them But, If the Schwarzchild radius of the BH is comparable to the size of the falling object: The material object would be squeezed to nuclear spaguetti, according to standard knowledge.

-

What Makes the E3 Comet Green?

I've just found this, but wouldn't know why that's the case: (My emphasis). From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/C/2022_E3_(ZTF) Maybe you can make something out from this.

-

Is Carnot efficiency valid?

So the answer to the question is a resounding yes! Carnot's efficiency formula is valid. There's no reason to believe its validity depends on heat being a fluid or not* --with our modern understanding being it's not, and Carnot's reasoning being the 1st stepping stone towards understanding it must somehow be quantifying elementary dynamical processes, which leads to the concept of entropy. There's no reason to believe the engine eventually grinding to a halt has anything to do with efficiency calculations**. There's no reason to believe the time it takes to complete a cycle --or thousands of them-- has anything to do with efficiency calculations. And finally, there's no reason for me to believe super-busy OP --with 113 comments at the time I'm writing these lines-- will ever even bother to address any of my comments. * If the fluid happened to correspond to a conserved quantity, it wouldn't make much of a difference, TBH. It's a conserved quantity that must go somewhere --for all that Carnot's reasoning is concerned. "Phlogiston" is a place-holder for a concept that was better understood later. ** Mind you, if the engine lost 0.00000000000001 usable energy every cycle, it would eventually grind to a halt anyway. Mind you also, @swansont's observation that, already gives you another clue: Under otherwise fixed conditions, re-scale Tc/Th, and things will get better in terms of efficiency. That's not direct proof, but certainly a good "thermometer" --allow me the conceptual pun-- that Carnot's reasoning is spot on. PD: 1) I said before something to the effect of "entropy leaking out." That wasn't quite right. You see, entropy is not a conserved quantity, so that was, strictly speaking, incorrect. But it can certainly go up and up for the whole universe, and it does reflect a loss in usable energy --something that can be exactly quantified by means of Gibbs or Helmholtz free energy, as the cases may be. And it will, as soon as you deviate in any way from the case of a 1-phase ideal gas ideally separated from the heat reservoir --and thereby exchanging both reversible work and heat-- by means of these "ghostly," non-existent walls that Carnot once imagined. 2) @Tom Booth In every reasoning you've deployed so far, you're counting irreversible work bluntly as "work" in the sense of Carnot. That's a blunder of such proportions that I don't wanna get involved in your reasoning any more. It will only lead to one mistake after another. When irreversible work is done, and you don't do anything to store it in any way in the form of state of the system, IOW, it leaves no record, it's as good as lost. Gone, forever, bye-bye. It's there, but you no longer know where it is. Nothing in the system's state reflects it's been done, or whether it came from work or from heat transfer. So you're tampering with concepts that are ambiguous if you try to interpret them in terms of Carnot's formula, and thereby, reversible thermodynamics.

-

Is Carnot efficiency valid?

Perhaps "upper bound" are the words to look for here? It definitely sets a theoretical upper bound in terms of energy obtained to energy invested ratio, having nothing to do with time --how long the machine is running, as you pointed out before--, or with whether the machine will eventually stop or keeps going forever --as Swansont pointed out. Because the Carnot cycle is defined in terms of state variables --due to all intermediate states beeing equilibrium ones-- and because an ideal gas has no internal mechanism to hide energy other that its pressure, volume, and temperature, no matter how many contraptions or intermediate complications we introduce, this upper bound cannot be overcome. The dynamics of this discussion does remind me of that of a Carnot engine, with a reservoir full of an inexhaustible resource, and the corresponding sink that can take any amount of such resource without in any way changing its state.

-

Is Carnot efficiency valid?

Those are excellent points that partially overlap with what I was thinking at this point. A Carnot cycle is an extreme idealisation. When I said before it's just based on (1) Conservation of energy (2) Existence, to a good approximation, of heat reservoirs I wasn't quite thorough. You need the gas doing the work to be ideal. You were quite right when you said, If the "working agent" is an ideal gas, and all the intermediate states are of equilibrium, its energy exchanges with the rest of the universe can be expressed as proportional to its temperature. Thereby Carnot's limit as a function of both temperatures. It's not --as OP has been repeatedly suggesting-- because the basic concept of efficiency is based on temperatures. It's not. It's based on energy exchanges. Anything, repeat anything, that deviates from this behaviour, would result in further "leaking out of entropy" to the rest of the universe and will make things worse in terms of efficiency. This is intuitively clear and only properly understood once the concept of entropy is introduced. It would be an interesting exercise --which I'm not going to do-- to replace the gas for a real gas, with an equation of state more similar to Van Der Waals, a virial expansion, etc, to see that things would only be made worse with real gases --never mind mechanical elements that introduce irreversible work and consequently extra dissipation. Another interesting approach would be a treatment based on statistical mechanics, which allows you in principle to make the isotherms not exactly isothermal, and introduce fluctuations in temperature.

-

Touching objects

Sorry. I was interrupted and then forgot. I agree.

-

Touching objects

First, we should agree on what the basic "objects" are. Quantum field theory tells us that those are quantum fields. Quantum fields are kind of "instanciation machines" for their quanta. These quanta are discrete jumps in the fields that we recognise in 2 ways: (1) Mathematically: they carry irreducible representations of the Poincaré group (2) Experimentally: They show themselves as discrete excitations on experimental equipment consistent with the values of energy/momentum/angular momentum that the theory implies The second one is more or less clear, I'd say. We never find "half an electron" hitting anywhere. The first one means that these fields factor out in terms that, in turn, cannot be further factored out into parts that mathematically represent translation, rotation, and motion at a speed.

-

Touching objects

Very good explanations here, so there isn't much of significance that I can add here. Just another rephrasing of the same idea. The whole concept of "touching" rests on the assumption that one thing is "here" and the other thing is "there," and that this assumption can be pushed to any scale we want. Quantum mechanics tells us that's an illusion. All the concepts involved must be reviewed: "Here"/"there", "one thing"/"the other thing", and "being". It's as @Genady says, It's very radical.

-

Early Human spreading on earth

Thank you. South Asia is a big puzzle.

-

OT posts split from New theory of evolution

(My emphasis.) Advise: Go back to your second incarnation and borrow a page from his book.

-

Early Human spreading on earth

Here's the paper with the find that Denisovan ancestry reveals two distinct pulses of Denisovan genes: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29551270/ And here's a paper based on applying Bayesian methods with a bundle of plausible models as contrasting hypotheses, and finding that there seems to be support for a "third" --meaning distinct, but genetically equidistant between Neanderthals and Denisovans-- group of humans: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-018-08089-7 I learnt about these papers in this wonderful podcast by Stefan Milosavljevich: I always think twice before recommending a YT channel. This one is prime quality. Número uno...

-

Early Human spreading on earth

-giggle Sorry, I should've said "a fourth group of humans". Or fifth, or even sixth... Let's just say one more. We do have pretty good physical evidence of ourselves.

-

Early Human spreading on earth

That's quite correct from what I remember too from the mid-'10s. But we must stay tuned, because "Denisovan studies" is a very active field lately. I've recently read that experts are finding traces of Denisovan traits in native Americans. The study is based on protein analysis, rather than DNA. It has to do with the structure of the lips. https://www.sci.news/genetics/native-americans-lip-shape-gene-denisovans-09330.html I've also learnt that a third group of humans approximately contemporaneous of Neandertals and Denisovans is being guessed at based on statistical analysis. I'm trying to get more info on that.

-

A Probability Question.

This is an interesting twist. Denominator expansions should make sense and therefore provide a basis to partition the sample space into significant exclusive propositions. Otherwise, one could end up saying things like, eg, P(outcome of coin flip = heads) = P(outcome of coin flip = heads| angels have wings) + P(outcome of coin flip = heads| angels do not have wings) Pretty soon we can get confused by the "logical span" of common language. Angels neither have wings, nor haven't, simply because angels do not exist. We simply cannot assign probabilities to any of both.

-

A Probability Question.

I agree. But OP seemed to understand the numerator and be only concerned/confused/curious, as the case may be, about the denominator. And the denominator is P(B)=P(B|A1)+P(B|A2)+P(B|A3)+... for every which Ai in the sample space of the A's. Feel free to correct my English anytime, by the way. Conscience is every bit as important as consciousness.

-

A Probability Question.

P(B) is P(B) no matter what A, so it's P(B) = P(B|anything) rather than everything. Language can be a naughty little helper.

-

Is Carnot efficiency valid?

I've been reading the arguments back and forth and I'm still missing something here. I have to confess I need more reading. Carnot's argument about the efficiency of heat engines is, from a logical POV, based on two assumptions --correct me anybody if I'm wrong: 1) Conservation of energy 2) Existence, to a reasonable degree of approximation, of heat reservoirs, ie, systems so big and thermodynamically static* that they can exchange any amount of thermal energy necessary --or irreversible work-- for the engine to work between the higher-temperature reservoir and the lower-temperature one. As one famous argument by Sagan goes, extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof. Because for Carnot's argument to be flawed it would require either 1) or 2) to be wrong, extraordinary evidence that either one of them is the case is required. It seems that the OP leans on the side that heat reservoirs are nothing but monumental abstractions with no basis on real physics. A claim that seems ludicrous to me. A further qualification could be necessary, which is the distinction between reversible work and irreversible work. Carnot's argument, AFAIR, relies only on the concept of reversible work. Irreversible work is, to all intents and purposes concerning thermodynamic arguments, pretty much indistinguishable from heat losses or gains, and can only be detected by means of precise calorimetric measurements, in principle. After a short time, any irreversible work will have leaked into the "worked upon" system in the form of heat. But --and it's a big 'but' implied, I think, by other members too--, the more a system resembles a heat reservoir, the more difficult it becomes to make precise measurements of heat loss --never mind it coming from irreversible work done. If a system can absorb or release any sizeable amount of heat --or irreversible work, like eg the motion of a blender-- without significantly changing its temperature, how can you be sure of the amount of energy it has received or released by means of calorimetric measurements based on known heat capacity/specific heat of such reservoir? What's more, how can you be sure that the conclusion to be drawn is that Carnot's efficiency formula is not correct? Wouldn't it be reasonable to demand from you that you design an engine that improves that? I mean, build a heat engine that delivers an efficiency better than that provided by Carnot's argument --kitchen availability pending. Also --and no minor point: I apologise if I've misunderstood any of the points under discussion. I need more time to get up to speed. * Both as compared to the engine.

-

The Paradox of thinking

Can a part of something map the totality of that something? Can a code-key pair decode the whole message it's a part of? Think about it. Maybe the answer is "yes." If so, it would have to be an exceptionally clever code-key pair. So I suppose my answer is "I don't know."

-

Viruses replace antibiotics

Right off the top of my head, using bacteriophages by means of suitable biotechnology is by no means a crazy idea. After all they're --what-- a couple thousand bases in their nucleic acid sequence? I'm guessing the reason why it hasn't been proven efficient might be related to the human body's immune response to pieces of alien DNA/RNA set loose in the body fluids. But I don't know. Maybe @CharonY --who is the resident expert in bio-- might find some time to answer the questions I'm just able to guess at right now. I do remember reading that people were considering this option again.

-

Viruses replace antibiotics

Viruses that target bacteria are known as bacteriophages. Bacteriophages have been tried as possible medicine. The idea is at least a century old or more. It is my understanding that the level of success was very limited. Experts can give you a more complete account. Google for "bacteriophages as antibiotics" and you will find many entries.

-

How the human eye could destroy quantum mechanics

This all seems to belong in the decades-old ongoing mindless hullabaloo about quantum mechanics and consciousness. If there's something that's clear about quantum mechanics and the process of measurement is that it's nothing to do with consciousness necessarily, but with quantum mechanics of open systems and dissipative processes. Conscious processes sure involve dissipation and quantum mechanics of open systems.

-

How the human eye could destroy quantum mechanics

How would the human eye destroy quantum mechanics? And if so, in what way is a human eye essentially different from any other photo-detecting device? --Never mind entanglement.

-

Can Stern-Gerlach spin alignment be seen as a result of EM radiation of precessing magnetic dipole?

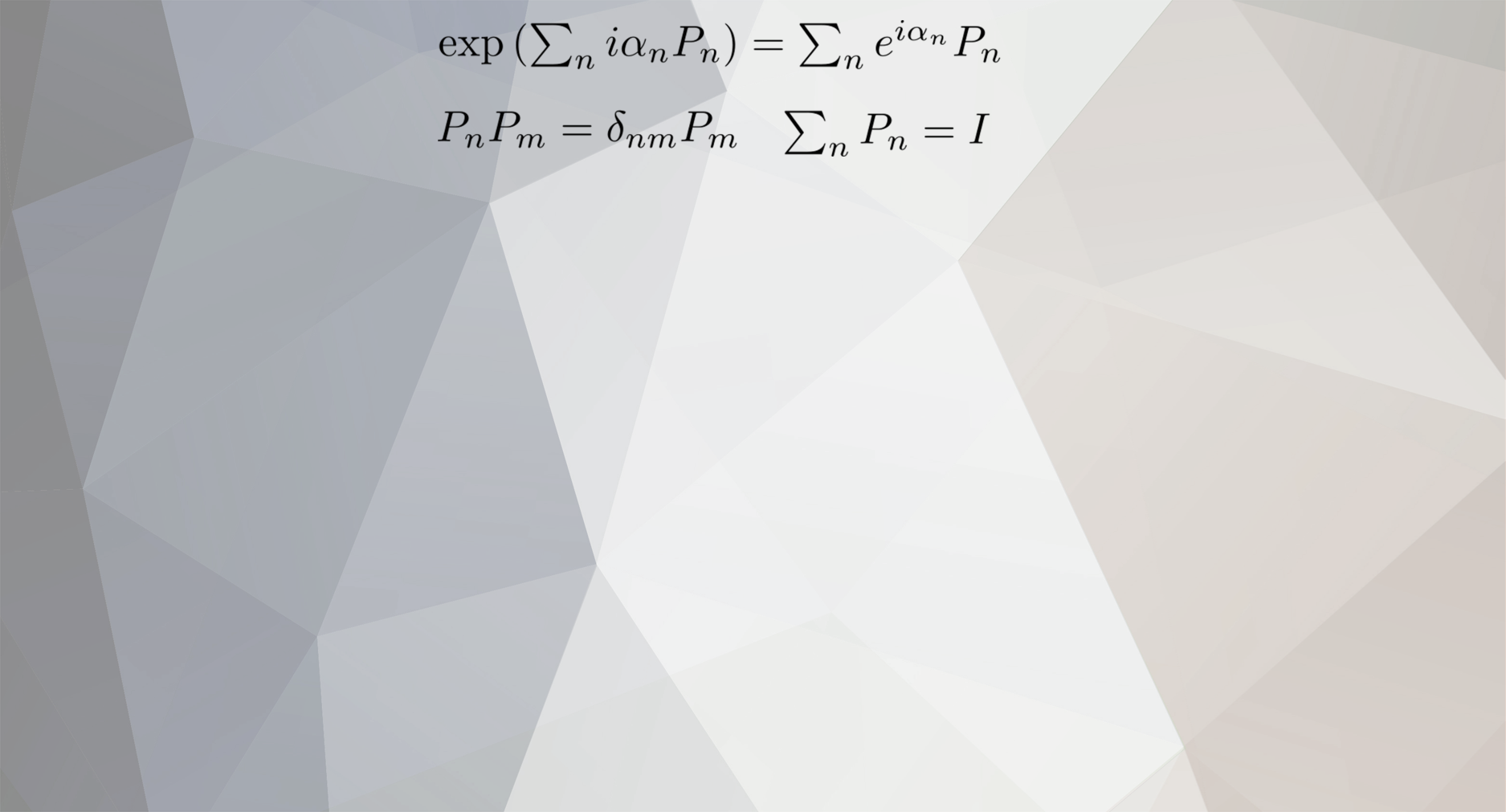

I must have missed it. I made a mistake. The SG experiment is not about charged particles. It's about particles with a permanent magnetic moment. They'd better be non-charged if you want to show just the beam-splitting effect without any qE Lorentz dragging term. Anyway, the force (classically) is a vector gradient of the effective potential energy term. You can do quantum mechanical calculations to show that --quantum mechanically--the beams split into 2S+1 levels. No purely classical calculation can give you that. The essence of this calculation is that (1) There is an inhomogeneous magnetic field in the window of the Stern-Gerlach device, and (2) the states of the particles can be described with a quantum-mechanical function that has 2S+1 distinct basis states. Use of vector identity, ∇(A⋅B)=A⋅∇B+B⋅∇A+A×∇×B+B×∇A allows you to expand, \[ \nabla\left(-\boldsymbol{\mu}\cdot\boldsymbol{B}\right)=-\left(\boldsymbol{\mu}\cdot\nabla\right)\boldsymbol{B}-\boldsymbol{\mu}\times\nabla\times\boldsymbol{B} \] where μ is the magnetic moment of the particles --you can think of gaseous paramagnetic Ag atoms as an example-- and B(z) is the z-dependent magnetic field inside the window. Because the window is very small, you can do a Taylor expansion, \[ \boldsymbol{B}\left(z\right)\simeq\left[\boldsymbol{B}\left(0\right)+z\boldsymbol{B}'\left(0\right)\right] \] Because quantum mechanics of spin introduces a discrete set of states --e.g., S=1/2 has 2 states--, you can expand the incoming states with, \[ \boldsymbol{\mu}=g\frac{\hbar q}{2mc}\left(\begin{array}{cc} 1 & 0\\ 0 & -1 \end{array}\right) \] Use of the quantum mechanical evolution operator with, \[ e^{-iHt/\hbar}\simeq e^{\left(\boldsymbol{\mu}\cdot\nabla\right)\boldsymbol{B}\tau/\hbar} \] (valid only for the small time τ the particles spend inside the window), you can show that the salient states are waves deflected in momenta by amounts --S=1/2--, \[ \triangle p_{z}\simeq\pm g\frac{\hbar q}{2mc}\boldsymbol{B}'\left(0\right) \] So part of the beam goes up, and the other goes down. You can see a more detailed discussion of this in David Bohm's Quantum Theory. No part of your calculation shows this. Instead, as @exchemist said, a classical situation would have the beams deflect in every other intermediate direction, as I said too.

-

Early Human spreading on earth

Yes, that's true. My comments were really meant about the prevailing direction. But, as you said, this is a huge subject, with many exceptions and several levels of "turbulence" around the average tendencies.