Everything posted by CharonY

-

US Constitution Article 1, Sections 9 and 10 removed from government website

I have no idea. To me, the crux is how society and its norm is developing and for a combination of reasons I don't think that I have a good sense how folks behave, much less Americans (I lived and worked for a decade there, but even some of the folks I know seem to have changed markedly over time). Sadly, only my most cynical predictions became true, not those I thought most likely, suggesting a deep disconnect to how I view the world and the way many others are. I think it could be a mistake to view things too much through a lens of political norms or maneuvering but it has become more about capturing the emotions and feelings of folks in the moment. Going viral has more impact on the population than well thought-out policies. A freak outrage situation has the power to change political norms and so on. Society has moved from potentially building on sand to full-on bouncing castle and I am not sure what predictions are worth anymore. So with that as basis my prediction is the following: whatever the most stupid outcome we can think of at this very moment, the reality will outdo it. It won't even matter if Trump goes or not- the ultimate check in democracies is the population and even outside of the US, I am not sure how long societal norms will hold and what a replacement would look like. And I worry that it will likely be memes.

-

Why infants and children died at a horrific rate in the Middle Ages?

Why not?

-

US Constitution Article 1, Sections 9 and 10 removed from government website

Maybe best to assume both.

-

Why infants and children died at a horrific rate in the Middle Ages?

The first line of scientific discussion, whether cold or friendly is to distinguish facts from opinion. The former have evidence. Take the STD argument, for example, it seems that you kind of suggest that STDs are a major driver of mortality but make no effort to substantiate that and/or discuss it in relation to other diseases for example. Same with pathogen diversity. There you just claim that geographic isolation also has to mean less diversity, which is just not true. Less travel means diseases do not spread as widely and if diseases are localized, there is a change of diversification. Geographic isolation can lead to speciation (we call it allopatric speciation). Things are a bit complicated, of course, but there is no reason to believe that there were fewer pathogenic species or strains around. Exotic is just weird as it assumes that there are places that are non-exotic. Folks are exposed to diseases where they are and attain immunity (or death) from what they are exposed to. I assume you mean to say that travelling individuals might be exposed to a broader diversity of pathogens but it is ultimately unclear what the relation to life expectancy might be. This is an entirely different argument- and while one can argue yes more resources for poor folks would increase their ability to survive, when it comes to infant mortality (remember, the topic of this thread), it is not clear whether that would impact it by much without modern medicine. I don't have the numbers here, but even the highest ranks of nobility has high infant mortality and if their mortality is only half of the average infant mortality, it would still be higher than folks in today's poorest countries (and definitely higher than the poor in high income countries). That again, is due to medical advances as discussed throughout the thread. Even a fictionally egalitarian country in the middle ages would not be able to achieve that. And given the fact that infant mortality is still lower in war-torn countries if there are at least remnants of medical support just shows how impactful modern medicine is (which would include emergency nourishment) There is no better (or worse) in evolution, so that doesn't make sense.

-

US Constitution Article 1, Sections 9 and 10 removed from government website

I think these are at least two questions. One is about whether the structures are de facto authoritarian and the second is at which point these structures cannot be remedied. To some degree, it will come down to definitions and semantics. I think one thing that is different from past forceful authoritarian regimes is that many patterns we see arises from societal factors that are successfully leveraged by the government, rather than necessarily due to government action as such. For example, evading accountability really only works because there is a cult-like belief among followers who are unlikely to switch votes. And that in turn is connected to the lack of political pluralism in the US, extreme partisanship and related factors. And these are also exacerbated by modern media consumption patterns. IOW, I think we have to think of modern authoritarianism in practice and action as a bit of a different beast than authoritarianism of the past. However if we don't focus on the mechanisms but at the outcome I think we can see at minimum the following: The power is concentrated in an unprecedented way (see also the unitary executive theory) and the separation of power as well as checks and balances are diminished or dissolved. There is virtually no accountability Non-governmental checks (e.g. media) are cowed and incentivized into collaboration and pre-obedience Dissent is increasingly met with forceful actions by governmental agencies (LA being an example using ICE and the military, other branches such as DOJ and FBI are similarly weaponized). Attempts to control economy, including tariffs and targeted support of allies and again, threats against enemies There are also other patterns that align with authoritarian governments and I think we also see a continued attempt to dissolve remaining barriers for full control. So if we don't see authoritarianism as a fixed threshold but rather a gradient, I would say that the US is pretty deep in it already and it looks beyond preparation at this point with actual actions underway. I think the reversibility is a huge questions and the midterms will give us the first hints on it, I think. That aligns with the maliciousness vs incompetence argument, I think.

-

Why infants and children died at a horrific rate in the Middle Ages?

Unfortunately, I do not see a lot scientific knowledge represented here. This sounds more like a moral argument. The main topic was about infant death but all you are saying here is that yes, modern medicine is preventing deaths and without those life expectancy is likely lower. That would be pretty much universally true. If you had better medicine in the middle ages, more folks would survive. That is not a thing. Less travel means less spread not less diversity. In fact if there are more isolated pockets there is also a chance that there is overall more diversity as there is less genetic flow and/or competition between pathogens in different populations. Makes no sense. What is an exotic pathogen? Also you only acquire resistance to those you are exposed to (i.e. local pathogens). I am not sure why you are so fascinated with STDs specifically. They have a long history with us, but so do many other infectious diseases. It is difficult to compare scope throughout history, but HIV is (was and is likely to be again) a killer of infants (to go back to OP) but it is a more modern pathogen. Not sure why low vitamin is snuck in here. Also you have been talking about infections the whole time, so I am not sure what the relevance to repeat it here again, but OK. While better social structures are likely always helpful, the issue is that in the middle ages modern medicine was not available. No level of redistribution of wealth would have solved that issue.

-

US Constitution Article 1, Sections 9 and 10 removed from government website

Hold on, what do you mean with prepping the field? It looks pretty much bulldozed and concreted. That looks more like flourishing touches. Granted, not all proposed actions have been taken yet, but I am not sure whether there are a lot of substantial barriers left.

-

US Constitution Article 1, Sections 9 and 10 removed from government website

It would be a bit of a relief if it was only Trump. The issue is that the whole system is in cognitive decline.

-

Anti-democratic political decisions in the Western countries

If y'all are willing to give up your liberties and democratic powers and go to a meaningless war for the sole reason that the gender orientation of a tiny fraction of the population confuses you, you probably didn't deserve those powers in the first place.

-

US Constitution Article 1, Sections 9 and 10 removed from government website

Because we are in the midst of a dumb and dumber version of 1984?

-

Why infants and children died at a horrific rate in the Middle Ages?

Maybe, but I am not entirely sure. The issue here is that whether there are populations that have sufficiently different famine rates so that we can spot potential selection. And obviously finding mechanistic evidence is going to be tricky as metabolic or other adaptations to famine are going to be more diffuse. One of the elements that folks have focused on is our propensity for obesity (i.e. storing fat). There is the hypothesis that most humanity is hunger-adapted in the first place. Now, there are populations who appear to struggle more for obesity and that potentially populations with very high rates of obesity might have genomic signatures of extreme adaptations to famines. However, these were arguments made when there was a rush for the human genome and a desire to look at things through an overly genetic lens with the expectation that high-throughput GWAS would yield terrific insights (the "thrifty genotype" was such an example) . I have not followed up on that, but I am aware that a couple areas of inquiry were pretty much just so stories with little supporting evidence. And I think folks have begun to be a bit more skeptical in the way genetic information have to be contextualized.

-

Why infants and children died at a horrific rate in the Middle Ages?

It depends a bit on the specific question. For example, do we see evidence of genomic adaptation to certain conditions? If so, then I would say yes. The issue is of course that we cannot say for certain, as we cannot really replay the past. Sethoflagos mentioned malaria, and the evidence we have is that a) alleles for sickle cell are more common in areas where malaria is found and b) there is a plausible mechanism for resistance against this pathogen where it was found that folks that are heterozygote are less likely to die from malaria (but homozygous folks, who are therefore symptomatic for sickle cell anemia) are at increased risk. Now, sickle-cell is a very popular example to teach human genetics for a number of reasons and perspectives, but there are a lot of other variants, associated with malaria including other variants of the HBB that do not associated with sickle-cell disease or other mutations that can cause other blood disorders (e.g. alpha thalassemia, which is caused by dysregulation of HBA, IIIRC, but also mutations in a chemokine receptor resulting in the absence of the Duffy antigen, which is used to enter cells by Plasmodium vivax (one of the parasites causing malaria). I am sure there are more that I cannot remember anymore. For other diseases it is a bit trickier, as few have this long, persistent and very strong selective pressure on human population. For example, there is the CCR5-Delta32 deletion mutation which confers resistance HIV. It arose very recently and has reached very high frequencies in Europe, suggesting that it is under positive selection. However, despite the nice narrative regarding HIV-resistance, HIV is actually not around for long enough to put enough pressure on the population to reach the measured frequencies. I.e. it can be tricky to figure out the true origin of genomic signatures. But there is also a more direct story. We carry quite a few viral sequences in our genome and while there can be many different reasons for their presence, one hypothesis is that some might have protective properties for example by competition with viral copies, inhibit synthesis of the "correct" product or somehow otherwise mess with viral functions.

-

Secrets of the world

Moderator NoteNonsense like this does not belong in a Science Forums. And this in fact gets it locked (and trashed).

-

Why infants and children died at a horrific rate in the Middle Ages?

It is one of the examples I love to show in class. Also in quite a few soil samples you will occasionally come across Y. pestis (probably also one of the reasons why you find them in ground squirrels and prairie dogs and other ground dwellers).

-

How can we inhabit Mars ?

Honestly, that just sounds like wishful thinking. Something that is quite popular among the techbro crowd. Real issues will somehow be magically fixed by technological advances while at the same time very current and actual challenges (ranging from undervaccination of folks to rise in antibiotic resistances) are ignored. It is not to say that those feats are impossible but there are no guarantees, either.

-

What is this CRISPR-Cas9? I’m reading this quote right?

That is a very unlikely approach. For the most part, we need our genes and just deleting one or even a full knockdown is normally not good news. It would also not use the actual benefit of CRISPR/Cas9, which is targeted editing (rather than full knockout or just a knockdown). What it can be used is to introduce functional alleles of genes to counter the whatever genetic issues there might be. Another idea is to to directly edit stem cells to replace the harmful with a non-harmful variant, but that can be a bit tricky. Usually you only get part of the reproducing cells (usually using a lentiviral vector) so it is often better to introduce something that can withstand the genetic issue. This is case the for sickle cell disease treatment, where a modified hemoglobin is introduced.

-

How can we inhabit Mars ?

Also, we don't really have any good idea regarding human developmental changes at lower gravity as well as long-term impact on health. What we know about is mostly from few individuals with few going longer than a year. There are also changes in the immune system (which likely is only partially related to gravity) and potentially other rewiring going on. But at this point much is just speculative. It is possible that the main issue is having issues going back to higher g, but there is also the risk that the our bodies are going to experience issues that are not easy to adapt to.

-

Why infants and children died at a horrific rate in the Middle Ages?

Oh there are absolutely cases where certain exposures in farming contexts can provide some form of immunity, especially to zoonotic diseases (though conversely, there is also a somewhat higher risk for agricultural workers to get sick). But I think TheVat might have been referring to the so-called Hygiene hypothesis (not to be confused with Semmelweis' hand hygiene concept). There, the idea is that childhood exposure is boosting the immune system provide overall better immune responses later in life. This is somewhat less well grounded. There is some potential link to things like autoimmune disease and allergies (especially asthma), but regarding net infections the jury is very much still out (at least to my knowledge). The main potential mechanism is low-level exposure to certain pathogens which then either provide immunity and/or cross-immunity. But for the most part it seems that with few specific exceptions, there really is no broad immunity to be gained from agricultural lifestyles and especially in poorer countries the above balance (protection against vs acquiring zoonotic diseases) seems to point to a higher, rather than a lower incidence of zoonotic infections.

-

Why infants and children died at a horrific rate in the Middle Ages?

I think that is somewhat more speculative or at least I have seen any particularly convincing data to this effect. What is known however is that many urban (but also some rural areas, later during industrialization) were heavily exposed to e.g. air, heavy metal and other pollution. These factors are known to adversely affect child development.

-

Why infants and children died at a horrific rate in the Middle Ages?

And just to reinforce a point made earlier- besides antibiotics, vaccines are probably the single largest contribution to population health. Treatments may or may not work, but they certainly do not prevent spread of infectious diseases and even if treated, they can still lead to significant health burdens. Vaccines on the other hand lower the overall risk of adverse health outcomes. Even just considering the last 50 years, where infant mortality has been cut down massively, vaccines have saved the lives in the order of 140 million children (each resulting on an average of 66 life years gained).

-

Why infants and children died at a horrific rate in the Middle Ages?

Absolutely- I forgot where I read it, but I believe that in the 1800s child mortality at birth was higher in urban centres (in rural areas, midwives were doing the work) and the hygiene findings after Semmelweis cut those down markedly.

-

Why infants and children died at a horrific rate in the Middle Ages?

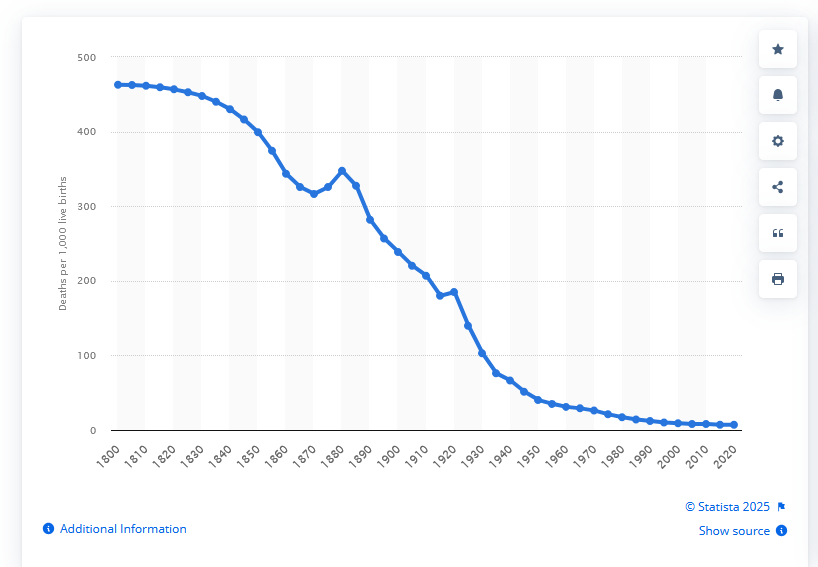

Essentially you can extend the graphs from 1800 all the way back to the middle ages as seen in the second link. In the US, for example, child mortality hovered around 45% through the first half of the 1800s. So rather than asking why child mortality was so high in the middle ages, one could argue that our "normal" child mortality is around 50% and things only started to change around 200 years ago. I.e. the modern times are the anomaly in our history (though the US is trying really hard to reverse that).

-

An appeal to help advance the research on gut microbiome/fecal microbiota transplantation in the US.

No let me try to clarify this: Already approved use -> normal usage no additional paperwork Off-label use -> no "formal" paperwork but physician needs to demonstrate that they have at least informed consent from the patient Obtaining Approval for not yet approved use -> Investigational New Drug approval application, typically an Investigator IND if the physician is administering and monitoring the treatment.

-

An appeal to help advance the research on gut microbiome/fecal microbiota transplantation in the US.

Sorry I wasn't clear, it was just to re-affirm that for FDA (or equivalent) approved use it would be IND, but the other pathway (i.e. without formal approval), would fall under typical off-label-use. I.e. the physician has to be able to defend the use, but does not require formal approval.

-

Death Map United States.

I am sure the food culture plays a role, but it seems France is extra-different. Italy, is only a bit lower than UK (~ 28 UK to ~20 Italy or something around that), Spain a bit lower than that (maybe 19). Greece is on the high end, with 33 (similar to much of Balkan/Eastern Europe). The Netherlands, which is similar to Germany in many regards is below Spain. And then there is France with around 10%.