Everything posted by Enthalpy

-

Extruded Rocket Structure

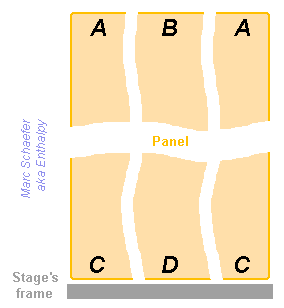

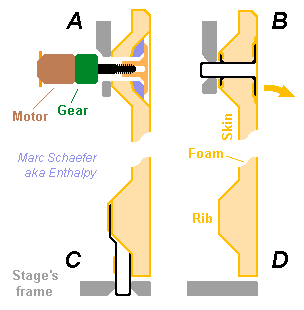

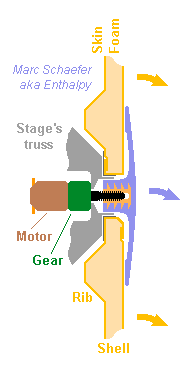

A launcher would separate the panels covering a stage above the atmosphere and during a strong acceleration. These favourable conditions permit to topple the panels to separate them. This script is cleaner, and it also tolerates better a few malfunctioning motors. A pin defines the vertical and lateral position at the panel's top center B, two geared motors and screws the radial one at the top corners A, two pins at the lower corners C the radial ones plus at only one corner the lateral one - the other hole at the stage's frame being wide. As the motors release the upper corners, springs (not sketched) push the panel's top outwards and the upper pin disengages, while the lower pins are still engaged, toppling the panel with the help of the acceleration. The panel falls to contact at D and, because the panel is curved, its rotation raises the lower corners and disengages the lower pins. The panel separates completely. This worked properly at Mach 1.3 through the lower atmosphere. I had B and A functions at the top center with a wide flat contact, and only one C at the lower center, further inwards. Here with big panels of limited stiffness, I prefer more A and C despite this can strain the panel; one can even design the curvature to apply the panel against the frame at B also - or have a single A at the center. A's and C's can be at 1/5 and 4/5 of the width for instance. Shape memory actuators - much smaller than for payload separation belts - are possible replacements for the geared motors and screws. Or even, wires burnt by an electric current. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Making Helium-3

Then it's only a matter of wording. By "decay" one usually understands "through radioactivity". Humans have some means to act on nuclides, typically by particle bombardment, which is less inefficient than X-rays. It is done at research labs, for instance to produce energetic neutrons in big amounts from a proton beam and investigate the effect of neutrons in materials. Or in particle colliders, usually for other purposes. Though, the faint probability to hit a nucleus, and the big chances to have accelerated a particle for no result, mean that nuclide reactions provoqued that way are not usable on commercial scale - if this is your intention. For instance, a 100MeV proton beam on a target of natural lithium makes neutrons, triton, alphas and the like. At big energy and money expenses for very little produced amounts, and technology won't improves that radically. Up to now, the only action from humans on nuclei on a big scale is through neutrons. They require no minimum energy to meet a nucleus and are produced abundently by uranium and plutonium fission. So to say all the man-made nuclides (in significant amounts) result from neutron irradiation at nuclear reactors. If someone could find a way, sensible economically, to produce some radio-nuclides without the special nuclear reactors, that would be extremely useful. Some nuclides are wanted by medicine and are produced by 3 to 6 reactors worldwide; some of these reactors are dangerous ruins, and when one stops, worldwide supply is short. The day-lived nuclides must be transported across the planet to the hospitals before decaying. Not satisfactory at all. One other nice task, as soon as someone finds how to command radioactivity, would be to exploit the decay energy of 40K. Abundent in the Oceans, no radioactive waste... Except that no-one has found a way.

-

Extruded Rocket Structure

Thanks for your interest! You're perfectly right, the extruded aluminium panels make a skin strong enough to be exposed to the wind, and naked foam is used on launchers to insulate cold tanks. I should have made it clearer. The throwaway shell of message #40 is only for stages sensitive to wind, and was meant for the Esc-B variant suggested in message #38. This one has naked satellite junk like multilayer insulation, very useful to store propellants until the apogee kick(s) while foam would let evaporate some propellant costly brought to orbit, but the better insulation consists of 6µm thin plastic films superimposed and demands a protection. Having foam, then multilayer insulation (MLI), then again foam is surprising, is it? We might perhaps have the multilayer insulation directly at the tanks, then only one layer of foam, if possible thrown away, but I see no good design nor operation then. At hydrogen's 20K, only helium and hydrogen are still liquid - air gases liquefy or freeze. The MLI at 20K would require vacuum (I believe this exists for small helium tanks, but is heavy and very special stuff) or be swept with hydrogen or helium all the time that the tank contains hydrogen. This is a difficult and costly operational burden; I prefer to keep 64+41kg foam at the tanks (this foam would be uneasy to throw away through the truss anyway) for simple and safer launch operations. With the foam directly on the tanks, once the hydrogen replenishment is stopped and the tank pressurized, one has 30 min in the atmosphere before a vapour valve must be opened. That's comfort. Once in vacuum, 8+6kg MLI give one week with no propellant evaporated. Foam alone would weigh a tonne to keep the propellants until the apogee. At launchers where hydrogen and oxygen tanks have a common head, a polymer honeycomb is said to work well. The gas in the combs freezes as hydrogen fills the tank, and they say this material keeps its shape and stays airtight; then vacuum in the combs insulates the tank. I may be wrong to distrust airtight polymers; then this honeycomb would be an alternative to foam.

-

Making Helium-3

The terrestrial proportion of 3He is 1.37ppm http://www.webelements.com/helium/isotopes.html http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Helium so for a significant thickness, the container's top would better be very narrow. That's a tiny proportion, but producing 3He is seriously difficult, especially because it swallows neutrons passing by - these neutrons used to produce it. It also takes patience, since the decay of 3H is typically on the route. Some people suggest to consume 3He in fusion reactors instead of the unavailable 3H, but: - Tokamaks are nowhere near using 3He, which is hugely more difficult than 3H - 3He could regenerate 3H in blankets there, but it needs one neutron per tritium just as lithium does, and only one neutron is created per consumed tritium... Neutron multipliers may work some day, but maybe not, and these would pollute as much as a uranium reactor does. Yuk. - These same people add: no 3He on Earth, but let's extract it from Moon's regolith, where it is hypothesized to be... Two impossibilities and a hypothesis, engineering works better on stronger bases.

-

Extruded Rocket Structure

Forces are diffuse at Ariane's Esc-B upper stage, so a light truss is easier to design with a lighter material than with a stronger one of equivalent strength-to-density ratio, hence the choice of aluminium AA7022. Magnesium alloy improves a bit over aluminium. AZ80A in T5 temper offers: 1800kg/m3, E=45GPa, 0,2% proof stress = 275MPa (tension) and 240MPa (compression). This gives about the same specific strength as AA7022. The AZ80A can be extruded, machined, welded; turn the tubes to the optimum thickness, leaving extra material fot the weaker weld seam (if equivalent to F temper: tension 250MPa, compression unclear). Magnesium doesn't burn, as know people who tried. The magnesium truss shape can keep aluminium's design; just put more thickness, and adapt the diameters a little bit. Because magnesium's density fits this particular task better, the design can fully exploit the specific strength, which saves 100kg roughly over AA7022. ---------- A truss of stronger but denser materials is difficult to design here. Titanium alloy Ti-Al6V4 would provide 4430kg/m3, 113GPa and 1030MPa (hardened condition) to 828MPa (annealed, maybe attainable at good weld seams). This exceeds aluminium and magnesium by far, almost equalling steel, but demands very short and narrow truss elements which make a cylindric truss too thin and make it weak against buckling through elliptic deformation. As it looks, long wide truss elements must themselve be trusses - not obvious to design nor produce. Isogrid tubes as truss elements are an other option. NiCoMoTi 18-9-5 steel's specific strength equals Ti-Al6V4, and 18-12-5 outperforms it, but it's even harder to exploit. Improving over AZ80A would be a performance. Also, it demands a heat treatment after welding, difficult at this size - or an other, heavier assembling method. ---------- Graphite composite is an obvious choice for light and strong design, excellent here as well. Exploiting the full strength would be about as difficult as for titanium, but even though the limit won't be reached, gaining mass is easy, because the material outperforms the others so much. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Making Helium-3

Usual Hydrogen to deuterium to tritium via neutron capture does work, but deuterium's section for neutron capture is very small. 3H converts to 3He spontaneously, yes. 3H is normally produced from lithium: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tritium#Production And: why should someone want to produce 3He by a nuclear reaction? It's a naturally occurring nuclide, and it separates spontaneously from 4He at 2K. Just cool enough, get one layer on top of the other, how easy.

-

Extruded Rocket Structure

A light shell meant to cover a stage truss, as suggested in the Esc-B message, can look like this, depicted here with a release mechanism: A sandwich of foam and aramide fibre composite is cheap, light and resilient to shocks - but I have nothing against honeycomb. Supersonic flight demands stiffness. The foam is thicker only at ribs to save weight. To throw away the panels composing the shell, geared electric motors turn the screws that hold the panels. This worked well on several projects, and I prefer it to pyro devices: testable many times with the components that will fly, safe, easy storage and export. Throwaway panels should be bigger than individual holes in the rocket's truss. As alternatives, the payload fairing could be lengthened to cover the upper stage as well; this often reduces the bending moments on this stage and enlights it. Or a separate stage's shell can use the fairing's material and release mechanism. When the stage uses satellite junk like multilayer insulation, its shell can be thrown away at the same altitude as the fairing, say just after. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Extruded Rocket Structure

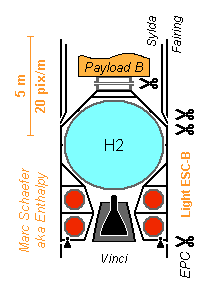

Ariane V's upper Esc-B is rumoured at 5950kg. This shattering dry mass reduces GTO (gesosynchronous transfer orbit) capacity, hampers GSO missions, nearly precludes transfers to Jupiter and beyond. Here's my alternative. This design has no structural tanks of extruded material, as it would complicate the excellent insulation that keeps hydrogen until the apogee burn. Polymer belts hold balloon tanks in a structural truss. A superinsulation that resists the wind would enable other designs. The elliptic hydrogen tank is of 200µm brazed maraging steel, plus 20mm foam so hydrogen warms by 0.6K after 10mn in air, and 5 plies of multilayer insulation for 0.07K after 10h in vacuum. It weighs 180kg with polymer belts. Already 10 plies would enable a week-long Moon mission; a 200 days Mars mission better has active cooling. Two torus for the oxygen shorten and lighten the stage. With 100µm steel, 10mm foam and 3 plies, plus the belts, they sum 123kg. Electric motors and screws can adjust some belts against thermal expansion. The outer part of the truss, similar at each level to the Soyuz interstage with 12 nodes, shall break at 6MN*m or 4.4MN. I couldn't check by hand the truss' global bucking, but only one nodes level (near the equator of the hydrogen tank) makes a straight cylinder. Welded (screwed at some places) AA7022 tubes make it, a section example being D100m*e2mm, summing 557kg. The inner part of the truss holds half of 24t oxygen and shall break at 2*5.5g; it stiffens also the outer part. AA7022 tubes there range from D70mm*e1mm to D80mm*e1.1mm, summing 163kg. 11kg of similar stuff hold the Vinci. The bistage conical adapter to an 8t payload is built the same way and weighs 35kg; heavier individual payloads to Leo or Gto have a special adapter. A shell on the truss protects the tanks from wind. Its sandwich panels have guessed 193g/m2 skins of aramide composite and 10mm foam thickened to 40mm ribs on 20% of the area. D5.4m*h6.0m weigh 121kg. The long Vinci is estimated at 280kg for want of manufacturer data, its actuators at 10kg. Vernier and roll engines (20kg) could burn gaseous hydrogen and oxygen at 1bar, or better, have electric pumps to burn the liquids at 25bar; as multiburn apogee engines, they would then outperform slightly the Vinci. They save separate tanks. Adequate chambers and nozzles exist at DLR. The separation belts, some auxiliary tanks and pipes account for 100kg; sensors, transmissions, control and steering for 300kg; unlisted items for 100kg. The dry stage weighs 2000kg, or 71kg per ton of propellants. With a second Vinci and dropable nozzle inserts for atmospheric operation you have a single-stage-to-orbit. Tanks holding more than here 28.2t would be nice, since this stage puts some 9.5t in GSO and 4.8t in transfer to Jupiter. Electric engines and screws can hold the shell panels, to drop 121kg just after the fairing, gaining as much payload. Maraging tubes would make a lighter (-150kg?) truss, but only if cut by laser or water jet to the shape of small frameworks; or make the tubes of carbon composite. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

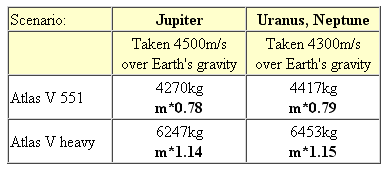

Atlas' capability on escape trajectories is less than I estimated, here a new attempt: Mass at all steps of the mission can be multiplied by 0.78 or 0.78 - or take an Atlas V heavy. Because the Esc-A stage weighs fat 4540kg, Ariane V underperforms Atlas V 551. The Esc-B is rumoured near shattering 5650kg after removing the equipment case, so Ariane V ME would but outperform Atlas V 551. Even the specially-designed Esc-B weighs 200kg per ton of propellants and Ariane 6 shall use a similar stage - the competitors have 112kg/t at the antique Centaur and develop composite tanks. Time to wake up maybe?

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

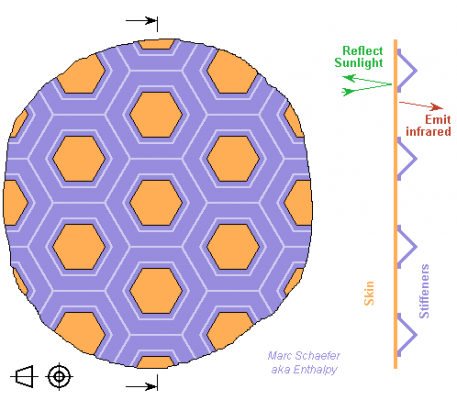

Usual honeycomb sandwiches with 0.3mm aluminium skins are heavier than desired for the concentrator. Space technology has probably lighter ones. Here I suggest a different process. Nickel parts are produced down to 8µm thin for elastic couplings; here 50µm shall provide enough local stiffness, with features about 20mm wide for ~80mm periodicity, as an experience-backed feeling. A few additional parts shall provide the global stiffness; consider brazing. The skin is deposited on a mould that gives the concentrating shape and preferably the optical smoothness. The reflecting layer may be deposited before. Then a thick layer is deposited temporarily on the skin and patterned to the hills and valleys; rocket cooling jackets use wax for that. The nickel stiffeners are deposited on the skin and the hills. The temporary layer is removed. A rear skin could be added on the stiffeners using a new temporary thick layer to produce a complete sandwich. This can be lighter if the skins get thinner. Once the several layers achieve enough stiffness, the reflector can be removed from the mould. Other parts can be produced this way, for instance antennas, or Sunlight concentrators to produce electricity. Other possibilities exist, for instance a sandwich of metal skins and thin balsa wood. The heat conductance suffices, but I like the all-nickel contruction for uniform thermal expansion. The Astromesh antenna is big, unfoldable, and its weight would nearly fit, but it's not a precise and efficient optical reflector up to now. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

One candidate to resist corrosion by vapour at 2400K is ZrO2 stabilized with Y2O3. For conductivity and if possible, zirconia should only cover a metal like tungsten or tantalum. If 2400K are sustainable, expansion from 2000Pa to 1Pa brings isp=3591m/s=366s. Main belt comets orbit rather at 3.1AU, some with a small inclination; only 6 bigger are known up to now, many more are expected. Spiralling from there to Mars takes (my mistake) 7210m/s, leaving 1/7.45 of the initial mass. The lower temperature reduces the heat leaks, but scaling only by the isp, and at mean 2.11AU from Sun, thirty D=4.7m engines eject 18g/s=1558kg/day vapour, or 2846t over 5 years, which would leave 441t near Mars with little inert mass. Sixty D=12m engines from an SLS fairing would deliver over 10 years 11500t water near Mars. The D=80m pond is 2.3m deep. Several thousand tonnes water boiled in few dm3 must be very pure to avoid scaling. Do it as you can. --------------- Some uses and engines need water, others oxygen and hydrogen, still others just hydrogen. At Mars, the same thirty D=4.7m concentrators can power turbines to produce 137kW electricity if pessimistic http://saposjoint.net/Forum/viewtopic.php?f=66&t=2051 of which 60% efficient electrolysis splits 0.29mol/s=450kg/day. The whole 440t take 2.7 years, resulting in 49.2t hydrogen. A cryocooler to keep the propellants liquid is described in the same linked topic. Whether water, only hydrogen, or as well oxygen are wanted, I find that transporting ice from the main belt by ejecting vapour takes fewer concentrators than making hydrogen at the main belt. --------------- At Mars or Earth, propellants brought from outer space are better kept near the planet than landed: the lighter crew or payload shall join the heavier propellants. An elliptic orbit, a high orbit or a Lagrange point are candidates, as is known. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Reduce PH of water using Hydrochloric Acid

pH=11 means 10-3 mol OH- per litre. 59,000 L water contain 59 mol OH-, to be neutralized by 59 mol of pure HCl or 2.15kg. If 33% is a mass concentration, it takes 6.5 kg, or about 6 L. pH=9 or 10-5 mol OH- per litre needs you to neutralize with 1% accuracy, but the pH=11 measure isn't so accurate, so you need to mix and monitor the pH during the operation. If your pond is made of concrete, and if this has made pH=11 (which needs a good reason!), the pH may drift further over time and when the neutralization is conducted. Just wait until John Cuthber passes by. If I botched that, he will let it notice.

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

Hydrogen is the propellant that improves the exhaust speed over chemical reactions, but the Solar thermal engine accepts other propellants. Water at 2400K can give some 3000-4000m/s ejection speed, depending on the dissociation allowed by the chamber pressure - and if available in space, it enables big scenarios where the in-situ propellant needs no lengthy preparation. Corrosion is a serious worry, hence the 2400K. If metals don't survive hot vapour, ceramics may: MgO and ZrO2, with 100K less? Tantalum hafnium carbide? Imagine that we find main-belt comets of the proper size and clean enough http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Main-belt_comet they can refill a spacecraft's tank after a simple purification - faster and lighter than electrolysis. A part of the icy object can fuel the Solar rocket to bring the rest (or a different asteroid) to a remote location. To a Lunar orbit: too easy now with the Solar thermal engine! "Think big" means again: manned Mars mission. To a Martian orbit or Mars' surface, for more ambitious uses. Granting the engine some time enables a scale more pleasant than our present space tinkering. Take thirty 4.7m concentrators that fit in one launch: at mean 2 AU, each ejects 40kg/day vapour at 4030m/s, or together 2,200t in 5 years. As the travel from the main belt to Mars takes 4820m/s, it leaves 1000t water at Mars. That's a swimming pool of 2m*50m*10m. Enough to refill a rocket there to return to Earth, possibly after separation into hydrogen and oxygen. Or to grow vegetables? Mars' gravitation is only 30 times ice's heat of fusion, so chunks of some proper size may aerobrake and reach the ground but cause limited damage. Sixty 12m concentrators fit in one SLS fairing. These would bring in 10 years 26,000t water to Mars, or 5m*D80m: that's a pond. A duly megalomaniac inventor (salut Guy Pi) proposed to veer a comet off course and smash it on Mars for terraforming; still not quite the proper size, but it's a first step. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

The scenario I propose for Jupiter brakes there using the Solar thermal rocket. Same for the asteroids and the Jovian Troyans, which are return missions. I didn't check for Uranus and suppose it's impossible at Neptune. I know from previous scenarios that Mars is an easy target for the Solar thermal rocket. Work is in progress for Saturn, I'll try a bang-and-whistles mission like at Jupiter, if possible.

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

No probe has orbited Uranus; only Voyager 2 passed by in 1986, and knowledge improved slowly since then. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uranus http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exploration_of_Uranus http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voyager_2 We won't wait one and a half decade for a Hohmann transfer. The Solar thermal rocket shall send the probe there in 6 years, which means 12858m/s relative to Earth and 12355m/s relative to Uranus, without the assistance of other planets. [xls file joined] An Atlas V v551 (or an Ariane V Me - something with a wide fairing) shall put 5589kg to 4300m/s above Earth's gravity. Four D=4.57m Solar engines add 8558m/s to the remaining 2806kg as they eject 2783kg hydrogen in 42 days. The Solar thermal stage is thrown away before braking: 155kg tank, 300kg truss, 120kg engines, leaving 2231kg. A chemical rocket brakes by Oberth effect at the final orbit's periapsis: Small radius 30Mm and 19173m/s Big radius 600Mm and 959m/s Period 5.34 days Orientation as possible The escape speed is 19646m/s at 30Mm, so the probe arrives there with 23208m/s and must lose 4035m/s. The rocket burns 1282kg of 700:100 O2:H2 at 25 bar expanded to 84Pa in four D=0.8m nozzles to achieve 4699m/s=479s isp. Electric pumps take 14kW during 15min from a 28kg Li-polymer battery. http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/73571-rocket-engine-with-electric-pumps/ The pumped engines weigh 40kg with driver, the tanks 40kg, their supporting truss 100kg, leaving 769kg for the probe's frame, instruments, equipment including the battery. Few orbits are possible; this one looks useful. Landmarks: Uranus' radius is 25Mm. Are radiations known at 30Mm? Voyager 2 passed at 81.5Mm and radiations were easy there. The main rings span from 38Mm to 98Mm. They are equatorial, that is >90° to the ecliptic. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rings_of_Uranus The major moons are equatorial and span from 129Mm to 583Mm http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moons_of_Uranus The closest known moon is at 50Mm. Of 27 known moons, 7 are pictured. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy ======================================================================== Neptune resembles Uranus: similar mass and diameter, no orbiter ever, Voyager 2 passed by in 1989. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neptune http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neptune#Exploration http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voyager_2 Sending an orbiter there is about the same, just farther. An 8 year travel needs 14380m/s versus Earth and 15771m/s versus Neptune. The Solar thermal rocket starts again with 5589kg at 4300m/s above Earth's gravity, ejects 3106kg hydrogen in 47 days through four D=4.57m Solar engines to add 10080m/s, ending at 2483kg. 590kg of Solar thermal propulsion are thrown away. The probe arrives with 1893kg at Neptune to brake chemically by Oberth effect to the final orbit: Periapsis 28Mm, apoapsis 770Mm, period 7 days, orientation as possible. Cf equator 24.8Mmn, Voyager 29.2Mm, rings 41-64Mm, Triton 355Mm, known moons 48Mm-far At 28Mm, escape speed is 22091m/s, elliptic orbit 21700m/s Rings http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rings_of_Neptune Moons http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moons_of_Neptune Magnetosphere http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neptune#Magnetosphere The probe arriving at 15771m/s dives to 27143m/s at 28Mm where it brakes by 5443m/s in 15min. This consumes 1299kg of O2 and H2 in the same 479s engine as at Uranus, leaving 594kg in orbit. 170kg for propulsion allow 386kg for frame, equipment, instruments. =============== One fascinating option is to send sistership probes to Uranus and Neptune. Share the design, the production, the spare, the operation team, the science team - and launch both at the same epoch. Then, as teams are occupied by Uranus after 6 years travel, a 9.8 year travel to Neptune is more acceptable. This takes 13230m/s from Earth, just 3% mass difference with the acceleration toward Uranus, and arriving with 13201m/s at Neptune takes a 4035m/s insertion kick at the described orbit - same kick as at Uranus, same 769kg available. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

The high specific impulse permits a Jupiter mission that orbits several moons successively and observes in between the planet from varied distances. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jupiter http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moons_of_Jupiter The Galileo probe had 200kB of Ram and a magnetic tape, so a new design could carry improved instruments. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galileo_spacecraft Atlas V 551 (or Ariane V Me) can put 8900kg on a transfer orbit 1804m/s below geosynchronous, so it shall put 5459kg at 4500m/s above Earth's gravity. The Solar thermal rocket makes the rest, beginning with a 2 years 9 months Hohmann transfer (my mistake at the Trojans). 1596kg hydrogen add 4294m/s to Atlas' 4500m/s and Earth's 29785m/s, leaving 3863kg heading to Jupiter. 1411kg hydrogen accelerate by 5643m/s and leave 2452kg just above Jupiter's gravity well. Twelve D=4.57m engines take 175 days to brake at quasi 5.2AU, lengthening by almost 3 months; their collective consumption there is 93mg/s = 8.04kg/d. Similar concentrators can provide each ~500W electricity as I describe there: http://saposjoint.net/Forum/viewtopic.php?f=66&t=2051&start=20#p23867 They resemble the high-gain antenna as well. The craft falls to 11.5Gm distance to Jupiter and acquires 4705m/s. 321kg hydrogen brake by 1378m/s in 40 days, leaving 2131kg on the orbit (3327m/s) of one moon of the Himalia group that has four or five members. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Himalia_group The orbit is tilted by 27.5° so the wide launch window for this goal opens every six years. A part of the upper Hohmann kick would better combine with the capture to benefit from some Oberth effect. I suppose the craft must arrive below the Himalia orbit and brake over half an ellipse or nearly 125 days while rising to the Himalia orbit. Someone else shall develop the theory or guidelines for crafts with weak accelerations. The other small moons have unrelated orbit inclination; maybe some is accessible. The probe sinks from the Amalia orbit (3327m/s tilted 27.5°) to a circular untilted 6890m/s orbit, of radius 4.29 times smaller, by a Hohmann transfer. 321kg hydrogen give in 40 days the 2035m/s upper kick that de-tilts (1582m/s) and brakes (1281m/s), leaving 1809kg on the 61d elliptic transfer. 255kg hydrogen in few kicks totalling 32d brake 1884m/s, leaving 1554kg on the circular 6890m/s orbit. There, ten engines are thrown away (250kg), a 3905kg hydrogen tank (200kg), the truss that holds it (200kg) - though most of the truss could have been thrown right after the chemical propulsion. The probe continues at 904kg, braking slowly over many orbits as it consumes 15.5mg/s=1.34kg/d. 91kg hydrogen let dive by 1310m/s in 68 days and leave 813kg at 8200m/s around Jupiter, that is at Callisto. 158kg hydrogen let dive by 2683m/s in 118 days and leave 655kg at 10883m/s around Jupiter, that is at Ganymede. 135kg hydrogen let dive by 2862m/s in 101 days and leave 520kg at 13745m/s around Jupiter, that is at Europa. Here the probe might split a lander, throw away an engine or a tank... The following doesn't do it. 130kg hydrogen let dive by 3581m/s in 97 days and leave 390kg at 17326m/s around Jupiter, that is at Io. The engines (50kg), the 514kg hydrogen tank (55kg), a truss around it (45kg) leave 240kg for the probe's frame, equipment, instruments. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

The Pioneer and Voyager probes have seen interesting physics near 90 Astronomical Units. Grass isn't greener there, but it's something like the Termination shock, where our Sun doesn't fully define the medium any more. As well, we could better measure star distances by parallax, and check on the way the Pioneer anomaly and some general physics. Though, the probes were meant and equipped to investigate none of these, and took four decades - so shall we have a new probe there within ten years? This needs 42780m/s above Sun's gravity (or a bit less), meaning a start at 30252m/s over Earth's gravity and own 29785m/s. An Ariane 5 with the Esc-B (public data is incomplete) shall provide 4346m/s over Earth's gravity to 7345kg, oriented as 3199m/s forward and 2941m/s sunwards, so the perihelion is at 0.98 AU and gives 19+15 days to accelerate under 0.99 AU conditions of Sunlight and speed. A first stage ejects 4756kg hydrogen through fifteen D=4.4m engines to bring 12953m/s. The tank weighs 230kg, a truss 210kg, 11 engines 330kg, leaving 1820kg after separation. More stages would improve. The second stage ejects 1178kg through the four kept engines, to bring 12953m/s more. 95kg tank, 55kg truss, 120kg engines leave 372kg for the frame, equipment, instruments. Is a very low perihelion better? The heavier chambers reduced the payload in the case I checked. And if a mission needs a low circular Sun orbit, or a circular polar one, I feel a Solar sail better. Maybe astronomers would share the Square Kilometer Array, if it's for good science, and if the probe transmits as short bursts, or if a separate frequency wastes no observation time. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

Mercury needs 7533m/s then 9611m/s in a Hohmann transfer from Earth, that's why chemical rockets make detours by Venus and Earth and take 7 years with a big launcher. The Solar thermal rocket goes there in three months. Start as usual with 2793kg at 4881m/s above Earth's gravity: 537kg hydrogen provide the remaining 2652m/s at aphelion, leaving 2256kg. Two 4.6m concentrators take 15 days. 1216kg hydrogen give 9611m/s at perihelion, leaving 1040kg above Mercury's gravity. The two concentrators take 10 days. 112kg hydrogen used close to Mercury give 1245m/s to achieve if desired a low circular orbit (escape: 4250m/s). If pushing for 1/7 of the orbital period, where the kicks are about 88% efficient, this takes around one week and leaves 928kg. Mercury's orbit is eccentric (and tilted). The Hohmann transfer, from Jarret Mathwig's thesis, supposes circular orbits, so a slick mission planner would save performance. Some Oberth effect is also possible; trade isp for thrust there. Each concentrator may weigh 17kg and the stronger chamber 87kg, so both engines take 208kg. The 28m3 tank with thin steel, foam, multilayer insulation and polymer belts takes 130kg. This leaves 590kg on low Mercury orbit for frame, equipment and instruments. Orbit changes are possible. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

Samples from Phobos and Deimos, Mars' moons, are a mission easier than asteroid samples: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phobos_(moon) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deimos_(moon) From the Hohmann transfer, a supplemented Falcon-9 provides all the 2945m/s above Earth's gravity to 3414kg spacecraft, while Earth's atmosphere makes all the braking on the return leg. The Solar thermal rocket provides Hohmann's 2649m/s near Mars, then 2139m/s to descend to Phobos, some 216m/s to sample a dozen sites there, 789m/s to climb to Deimos, some 216m/s to sample a dozen sites, 1350m/s to climb and escape Mars' gravity, and 2649m/s to come back. This amounts to 10260m/s, easy for the Solar thermal rocket. The craft weighs 2758kg as is hovers at Phobos. At the moons, the engines operate at 2.1* thrust, or isp=800s, so 2* 12 hops of 1h each at 5mm/s2 comsume as much hydrogen as 684m/s at full isp. This needs only five 4.6m concentrators then. More thrust increase would improve. The craft weighs still 1494kg when arriving near Earth. Since thick regolith covers the moons, lighter samples should suffice, permitting a smaller launcher and craft. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

A mission similar to the main belt asteroids can bring back samples from Jupiter's Trojans: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jupiter_Trojan The main belt return trip leaves room for extras, like sampling both at 2.38 AU and 2.58 AU (+764m/s if you're patient); but Jupiter's orbit needs to care more about speed changes and mass. The 2-year Hohmann transfer needs 8793m/s over Earth's gravity at perihelion and 5643m/s at aphelion. If again a supplemented Falcon-9 puts 2793kg at 4881m/s, the trip takes 15198m/s. If the parts thrown away only compensated the samples, the craft would arrive at Earth at 822kg. 754, 744 and 472kg hydrogen are ejected; braking over 120 days at 5.2 AU takes 9 engines with 4.6m concentrators, and accelerating there only 6 engines. Concentrators weighing 1kg/m2 seem a reasonable effort, so each engine could weigh 30kg. Tanks of 100µm steel, 20mm foam and 50 layer insulation, hold by polymer straps, weigh 110kg for the first 754+744kg hydrogen and 55kg for the last 472kg - in case the first is thrown away. The sampling drill can stay there as well. That's room for samples, and for the ability to visit several Trojans. This would leave some 400kg for all craft functions and the re-entry capsule, not including the tanks, engines and 180kg souvenirs. Bonanza! Missions to Jupiter use the Oberth effect to brake there, but I suppose the Trojans are too far away. Bigger launchers, like Ariane 5 with the Esc-B, would give a stronger initial kick to a heavier payload, for instance both missions to the main belt asteroids and to the Jupiter Trojans at once. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

The Solar thermal engine's isp=1267s=12424m/s can bring asteroid samples to Earth . Take a Falcon-9 for its wide fairing; it puts 10t at 400km Leo. A Leo-to-Gso stage as I describe there http://www.scienceforums.net/topic/73571-rocket-engine-with-electric-pumps/#entry736092 used as an escape stage injects 2790kg at 4880m/s above Earth's gravity. A Hohmann transfer to 2.58UA in the main asteroid belt takes only 15 months http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asteroid_belt it needs additional 1093m/s near Earth and 4684m/s in the belt, while the return leg takes 4684m/s in the belt, and a capsule aerobrakes for free from 12.2km/s. Cumulated 10461m/s would leave 1200kg at reentry - but meanwhile samples were taken, and the craft has made manoeuvres. Braking 4684m/s takes 804kg hydrogen; over 30 days, it needs 7 concentrators of D=4.6m at 2.58UA. These are oversized at 1UA, and the diameter of a secondary or third mirror can limit the power if desired. The chambers for 2.58UA are lighter that previous estimations, and I'm confident that the concentrators can weigh <<3kg/m2, so each engine is maybe 30-50kg. This leaves mass for equipment and samples, all with a single stage. Fascinating: the craft pushing 0.4N per 100kg at 2.58UA can lift off a D=10km asteroid by its Solar engines, and hop from one asteroid to an other, taking samples at each one - maybe capture tiny asteroids provided it sees some with a reasonable speed. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

Escaping Earth or an other body is best done with one or few kicks at the perigee. The Solar thermal engine is bad here: its faint thrust used briefly at each orbit would take too long and demand too many concentrators. Escaping by continuous rise of a circular orbit is inefficient, letting a Solar thermal engine use as much propellant as an oxygen-hydrogen engine. Chemical engines shall escape planets. Providing little more speed at perigee than the escape minimum leaves much speed after escape because energy goes as speed squared http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oberth_effect so I checked for a high-energy mission how the chemical and Solar engines shall share optimally the provision of speed beyond escape. From 200km above Earth, where speed is 7791m/s and needs 3227m/s more to escape: An oxygen and hydrogen engine with isp=465s best brings 4054m/s = 3227 + 827m/s, leaving 4346m/s beyond escape; An oxygen and dense fuel engine with isp=395s best brings 3789m/s = 3227 + 562m/s, leaving 3561m/s beyond escape. The wide optimum adapts to practical arguments. The needed performance nears a Mars transfer or a direct injection in Gso. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

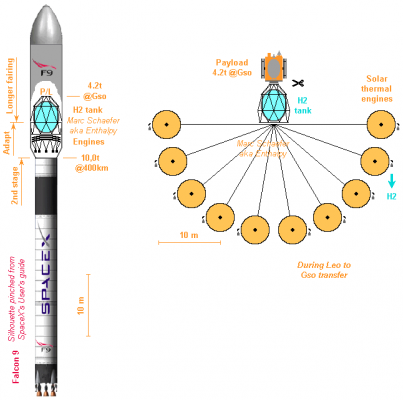

To bring a payload from Low-Earth- (Leo) to a Geosynchronous Orbit (Gso), a Solar thermal rocket would use its small push all the way to save time, but this takes more performance than the usual very elliptical transfer (Gto). From an equatorial Leo (sea launch, Alcantara...) the required Delta-V is the speed difference between the low and the high orbit, if I didn't botch it. Starting from 7675m/s at 6366+400km to avoid drag, the transfer stage must add 4600m/s to achieve the 3075m/s at 6366+35798km. This costs 741m/s more than the Hohmann Gto. From other launch sites, the orbit's inclination must be cancelled. The very elliptic Gto does it at apogee where speed is small, but the continuous push lacks this possibility. Fortunately, isp=1267s absorbs this as well. Kourou reaches 5.2° inclination at Leo. To estimate the added cost, I keep the inclination over the first 2600m/s, and compensate it over the last 2000m/s needed for altitude; the side speed to cancel is 462m/s (begin) to 278m/s (if done at Gso), so I take mean 370m/s. The engines shall push flat for 2*90° per orbit, and for 2*90°, tilted as 1,11*370m/s * sin = 1000m/s (1,11 because the tilted push extends 45+45° from the optimum point). When tilted, only 91% of the thrust is equatorial, so these 1000m/s cost 1097m/s performance, and the overhead nears 97m/s, totalling 4697m/s to Gso. A Gto would waste 15m/s from Kourou's latitude. Cape Canaveral reaches 28.5° (and Tanegashima 30°), giving 3779m/s side speed at 400km and 1505m/s at height, for mean 2642m/s. Here I tilt the thrust as a cosine function over one orbit. At maximum tilt, the relative components of thrust are S and C, kept for all orbits of the transfer, which is not optimum. Only 0.5*S and nearly (1+C)/2 act as a mean, so side 2642m/s versus 4400m/s along the path leave 73.5% efficiency: the total cost nears 5986m/s and the overhead 1586m/s. This wastes even more performance than de-inclining at final altitude but saves time. The optimum is obviously elsewhere - someone with a liking for it shall investigate. I take 5700m/s. ================================================================= A Falcon-9 shall illustrate the transfer from Leo to Gso - click to view the drawing's full splendor. Starting from Cape Canaveral, the launcher puts 10,0t on a 28,5° 400km orbit. The Falcon may need reinforcement for the longer fairing. Minus the adapter, the transfer stage starts with 9350kg. To provide 5700m/s as estimated previously, it ejects 3440kg hydrogen at isp=1267s. 20 days thrust (plus some 5 days eclipse) take 10 Solar thermal engines with 4.6m concentrators. Not that huge. The balloon tank of thin steel, foam and multilayer insulation weighs 143kg. Polymer straps hold it to a truss of welded AA7020 weighing 205kg that links to the launcher and the payload. A cryocooler keeps the hydrogen liquid. Each engine weighs 100kg, of which 50kg are the concentrator and 20kg the chamber, using nickel or niobium rather than tungsten where possible. 300kg of sensors, datacomms, control and unaccounted items leave a payload of 4262kg in Gso. That's roughly twice the capacity of chemical stages. ----- Here the Solar thermal stage is expended at each launch and continues to a park orbit. It can also come back to Leo, what ESA calls a "tugboat": Reusing it saves launch mass, even though the way back needs some hydrogen; It can bring a satellite down to Leo for repair; A lighter launch mission can bring extra hydrogen for a following overweight mission; The launcher can bring the hydrogen and the satellite separately. This puts in Gso the full launcher's Leo capacity; A flexible long-range vehicle between Leo and Gso can bring resupply or remote repairs to several satellites, push aside the lost ones... Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Quick Electric Machines

High frequency spindles for machine tools shall offer the highest angular speed for a given torque or power. Even if not required simultaneously, bigger maximum speed and torque from the same motor let the spindle accommodate more varied tool diameters - but this demands a higher possible linear speed from the motor. For instance the TCV-2 from Peronspeed illustrates it: http://www.peronspeed.it/scheda1.asp?idserie=6 for 10kW and 40,000rpm, the motor's gap of D=64mm (drawing there) runs at 134m/s already, so its stainless sleeve must be the limit, and winding graphite fibres instead, or a thin long steel sheet, improves it. Would friction stir welding benefit from higher speeds? This paper investigates 24,000rpm: http://www.niar.twsu.edu/researchlabs/ajt_presentations/Widener%20-%20Paper%2038%20-%20Presentation.pdf to reduce the forces. Marc Schaefer, aka Enthalpy

-

Solar Thermal Rocket

My answers to some points evoked here - sorry to be late... Interstellar travel does not exist, not even as a proof-of-concept, because we have no propulsion for it. A manned travel to Mars for instance would take under 100 days. Take submarine crews for that, they usually don't get crazy when confined over this lapse. Radiation pressure is 4.5µPa near Earth. This is 68µN on a 4.4m dish. It's the very reason why we don't use it every day for space transport. 2N by my Solar thermal rocket is unconveniently little, but usable for some missions. That said, I do like Solar sails, but we still need comfortable solutions for hectares and square kilometers of sail. I will not detail how to unfold and control the concentrators. This is not new technology; spacecraft designers do it better than I, for cases already much more difficult than the engine I describe. Multi-meter telescopes in space make pictures limited by diffraction, far below the micron. A concentrator that focusses Sunlight to make heat is nowhere as difficult. Its accuracy compares rather with a radio dish antenna, both in shape and pointing, for which a standard carbon honeycomb is perfect. The thrust must be arbitrarily orientable versus Sunlight. From Earth to Mars for instance, the craft would accelerate perpendicularly to the Sun's direction, but decelerate strongly Sunwards. Other missions have still other needs. In short: steer in all directions. If it simplifies other parts, especially the chamber, an added mirror (1-1.5% light loss, little mass, limited cost) is perfectly welcome. Steering without excessive optical aberration is nothing obvious, and I'm happy that my three mirrors show it's feasible, though optics designers will find better combinations. Any spacecraft will cumulate several concentrators (a reasonable number for some missions and designs) so the craft will control its attitude from independent orientation of individual engines.