Everything posted by Genady

-

What is gravity?

Yes, it is, in this sense: "This is extremely general. In any kind of gravitational field, as long as it is more or less constant with time, and not doing anything too radically relativistic, the coefficient in front of \(dt^2\) in the metric is always one plus twice the gravitational potential." Susskind, Cabannes. General Relativity: The Theoretical Minimum (p. 155).

-

Metric or Kronecker delta?

I'm at ease with the Schwartz's notation by now. It is as simple as mentally substituting \(A_{\mu} g^{\mu \alpha} B_{\alpha}\) every time he writes \(A_{\mu} B_{\mu}\).

-

Off-shell-ness of the Feynman propagator

I'm looking where exactly, during a construction of the Feynman propagator \(D_F(x_1,x_2)\), a particle goes off-shell. It is on-shell all the way until before the last step: \(D_F(x_1,x_2)=\frac i {(2 \pi)^4}\int d^3 k \int d \omega \, e^{-i \vec k (\vec x_1 - \vec x_2)} \frac 1 {\omega^2 - \omega_k^2 + i \epsilon} e^{i \omega (t_1-t_2)}\) The particle is on-shell here because its 4-momentum is \((\omega_k, \vec k) \), where \(\omega_k^2 = \vec k^2+m^2\). Integration variable of the first integral is 3-momentum \(\vec k\), where each one of the three component varies from \(- \infty\) to \(\infty\). Integration variable of the second integral is energy \(\omega\), which also varies from \(- \infty\) to \(\infty\). Now, we combine these integration variables into a new 4-vector \(k=(\omega,\vec k)\), where each component varies independently from \(- \infty\) to \(\infty\). This 4-vector is not a 4-momentum of anything and thus is off-shell for a simple reason that there is no shell for it to be on. It is just an integration variable: \(D_F(x_1,x_2)=\frac i {(2 \pi)^4}\int d^4 k \, e^{-i \vec k (\vec x_1 - \vec x_2)} \frac 1 {\omega^2 - \omega_k^2 + i \epsilon} e^{i \omega (t_1-t_2)} = \frac i {(2 \pi)^4}\int d^4 k \frac {e^{k (x_1 - x_2)}} {\omega^2 - \omega_k^2 + i \epsilon}\) Being a generic 4-vector, \(k\) satisfies \(\omega^2=k^2+ \vec k^2\). Being an on-shell 4-momentum, \((\omega_k, \vec k) \) satisfies \(\omega_k^2 = \vec k^2+m^2\). Substituting these above, we get the final form of the Feynman propagator: \(D_F(x_1,x_2)= \frac i {(2 \pi)^4}\int d^4 k \frac {e^{k (x_1 - x_2)}} {k^2 - m^2 + i \epsilon}\) The particle, which is on-shell, is not explicit in this form. Instead, we have a generic variable \(k\), which is a Lorentz invariant way to package the four integration variables, and which is not a 4-momentum of any particle. Evidently, there are no off-shell particles here.

-

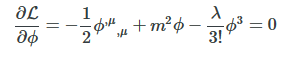

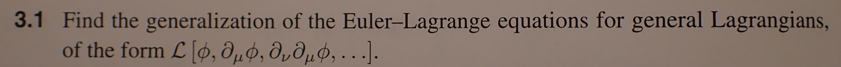

Symmetry breaking Lagrangian

Unfortunately, I can't read this post: and I don't know how his result is different from mine, but it seems that his EL equation is the same as mine, <<<<< which is different from <<<<<<< I disagree with the latter. We need to use the generalized EL equation, which I have already derived in this exercise: and got the answer compatible with this: (Euler–Lagrange equation - Wikipedia)

-

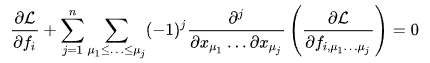

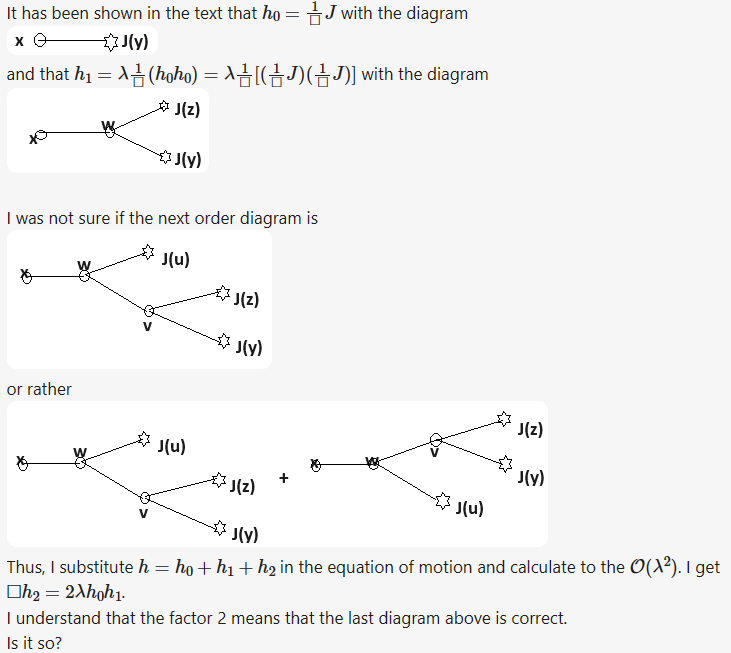

A toy Feynmann diagram

Write down the next-order diagrams for the equation of motion \(\Box h - \lambda h^2 -J =0\). Check the answer using Green's function method.

-

Symmetry breaking Lagrangian

Q: How many constants \(c\) are there so that \(\phi(x)=c\) is a solution to the equation of motion? A: Three. \(c=0\) and two solutions for \(c^2= \frac {3!} {\lambda} m^2\) Q: Which solution has the lowest energy (the ground state)? A: The potential energy from the Lagrangian is \[\frac {\lambda} {4!} \phi^4 - \frac 1 2 m^2 \phi^2\]It is the lowest for the non-zero \(c\): \(- \frac{3!m^4} {4 \lambda}\).

-

Symmetry breaking Lagrangian

This is a multi-step exercise. It would be very helpful if somebody could check my step(s) as I go. @joigus, I'm sure it is a child play for you. I'd like to make sure that I've derived correctly the equation of motion for this Lagrangian: \[\mathcal L=- \frac 1 2 \phi \Box \phi + \frac 1 2 m^2 \phi^2 - \frac {\lambda} {4!} \phi^4\] The EL equation: \[\frac {\partial \mathcal L} {\partial \phi} + \Box \frac {\partial \mathcal L} {\partial (\Box \phi)} = 0\] The equation of motion: \[\Box \phi - \frac 1 2 m^2 + \frac {\lambda} {3!} \phi^3 = 0\] How is it? P.S. As edit LaTex does not work, I add a typo correction here. The equation of motion is rather \[\Box \phi - m^2 \phi + \frac {\lambda} {3!} \phi^3 = 0\]

-

Where was the symmetry?

The advantage is, no deadlines.

-

Where was the symmetry?

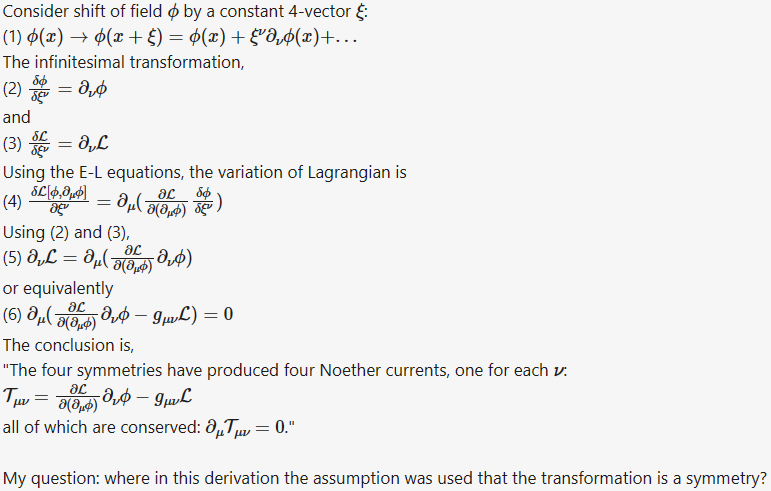

I think, I got it. The symmetry validates the equation (3), because this equation makes the variation of Lagrangian a total derivative, and this makes the variation of action vanish: IOW, without the symmetry, we can't go from (4) to (5).

-

Where was the symmetry?

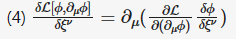

Rather than trying to fix the OP, I've prepared the text elsewhere and just post its image: A minor correction: the equation (4) above should rather be

-

Where was the symmetry?

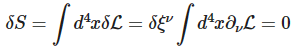

Here are steps of derivation of energy-momentum conservation: Consider a shift of the field ϕ by a constant 4-vector ξ : (1) ϕ(x)→ϕ(x+ξ)=ϕ(x)+ξν∂νϕ(x)+... The infinitesimal transformation makes (2) δϕδξν=∂νϕ and (3) δLδξν=∂νL Using the E-L equations, the variation of Lagrangian is (4) δL[ϕ,∂μϕ]∂ξν=∂μ(∂L∂(∂μϕ)δϕδξν) Using (2) and (3), (5) ∂νL=∂μ(∂L∂(∂μϕ)∂νϕ) or equivalently (6) ∂μ(∂L∂(∂μϕ)∂νϕ−gμνL)=0 The conclusion is, "The four symmetries have produced four Noether currents, one for each ν : (7) Tμν=∂L∂(∂μϕ)∂νϕ−gμνL all of which are conserved: ∂μTμν=0 ." My question: where in this derivation the assumption was used that the transformation is a symmetry? P.S. I am sorry that LaTex is so buggy here. I don't have a willing power to do this again. Ignore. Bye.

-

test

\[\phi(x) \rightarrow \phi(x+\xi)=\phi(x)+\xi^{\nu} \partial_{\nu} \phi(x) + ...\] \[\frac {\delta \phi} {\delta \xi^{nu}} = \partial_{\nu} \phi\] \[\frac {\delta \mathcal L} {\delta \xi^{nu}} = \partial_{\nu} \mathcal L\] \[\frac {\delta \mathcal L[\phi, \partial_{mu} \phi]} {\partial \xi^{\nu}}=\partial_{mu} (\frac {\partial \mathcal L}{\partial (\partial_{mu} \phi)} \frac {\delta \phi} {\delta \xi^{nu}})\]

-

Metric or Kronecker delta?

Thank you. All's well. Yes, I like the book otherwise, but it would be so much easier to follow if the indices were where they should be.

-

Metric or Kronecker delta?

Please, I really, really know this. I know this index gymnastics, lowering and raising indices, tensors vs. basis representations, etc. I appreciate your time, but there is no need to teach basics here. Let's focus. Back to my question. Let's take \(\nu=1\). If \(\partial_{\nu} \mathcal L = \partial_{\mu} (g_{\mu \nu} \mathcal L)\), then \(\partial_1 \mathcal L = \partial_{\mu} (g_{\mu 1} \mathcal L) = -\partial_1 \mathcal L \). Where is my mistake?

-

Metric or Kronecker delta?

They are different: \[\delta=\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix}\] \[g=\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 \end{pmatrix}\]

-

Metric or Kronecker delta?

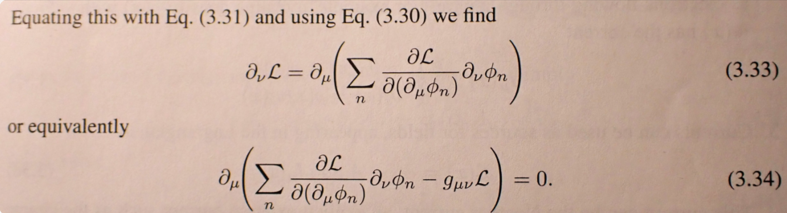

I understand this but I don't think it answers my question. This is what I mean: I can rewrite (3.34) so: \[ \partial_{\mu} (\sum_n \frac {\partial \mathcal L} {\partial (\partial_{\mu} \phi_n)} \partial_{\nu} \phi_n) = \partial_{\mu} (g_{\mu \nu} \mathcal L)\] Then, from this and (3.33), we get \[\partial_{\nu} \mathcal L = \partial_{\mu} (g_{\mu \nu} \mathcal L)\] I think, it is incorrect. It rather should be \[\partial_{\nu} \mathcal L = \partial_{\mu} (\delta^{\mu}_{\nu} \mathcal L)\] P.S. Ignore positions of indices; Schwartz does not follow upper/lower standard. The difference is between \(g\) and \(\delta\).

-

Metric or Kronecker delta?

My question is about the following step in a derivation of energy-momentum tensor: When the ∂νL in (3.33) moves under the ∂μ in (3.34) and gets contracted, I'd expect it to become \(\delta^{\mu}_{\nu} \mathcal L\). Why is it rather gμνL ? Typo? (In this text, gμν=ημν )

-

What is this unit step function for?

It is not technically homework, but it could've been if I were technically student. Just a new textbook to work on. I don't anymore read books that don't have equations. 🙃

-

What is this unit step function for?

Just to answer the OP question, It would not. Without the step function it would be \[\int dk^0 \delta (k^2-m^2) =\frac 1 {\omega_k} \] rather than \(\frac 1 {2 \omega_k}\).

-

Hawking radiation is produced at the black hole horizon, and other pop-science myths

A light that is produced by hot infalling matter between the photon sphere and the event horizon can still escape radially, right?

-

What is this unit step function for?

Thank you. I got it. My mistake was that when I replaced \(k^0\) with \(\omega_k\) I've missed that it can be + or - \(\omega_k\). The step function is needed to kill one of them.

-

What is this unit step function for?

The question: Show that \[\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} dk^0 \delta (k^2-m^2) \theta (k^0)=\frac 1 {2 \omega_k}\] where \(\theta(x)\) is the unit step function and \(\omega_k \equiv \sqrt {\vec k^2 +m^2}\). My solution: \(k^2={k^0}^2 - \vec k ^2\) \(\omega _k ^2 = \vec k^2 +m^2\) \(k^2 - m^2 = {k^0}^2 - \omega_k^2\) \(dk^0= \frac {d{k^0}^2} {2k^0}\) \(\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} dk^0 \delta (k^2-m^2) \theta (k^0) = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac {d{k^0}^2} {2k^0} \delta ({k^0}^2 - \omega_k^2) \theta (k^0) = \frac 1 {2 \omega_k} \theta (\omega_k) = \frac 1 {2 \omega_k}\) However, the point of the unit step function there is unclear to me. Wouldn't the result be the same without it?

-

Hawking radiation is produced at the black hole horizon, and other pop-science myths

I agree, the vagueness of such statements is an issue. Next time somebody says, "Hawking radiation is generated just outside the event horizon", I will ask first, how far is "just".

-

Hawking radiation is produced at the black hole horizon, and other pop-science myths

Yes, for an audience that thinks that Event Horizon is an actual physical structure, there is no difference between an approximation and a myth.

-

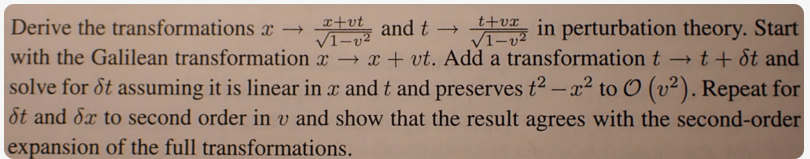

Derive Lorentz transformations in perturbation theory

I've arrived to an expected answer, but I am not sure at all that the process was what the problem statement wants. First, I considered \(0=(t+\delta t)^2-(x+vt)^2-(t^2-x^2) \approx 2t \delta t - 2xvt - v^2t^2\). Ignoring \(O(v^2)\) gives \(\delta t=vx\), i.e., \(t \rightarrow t+vx\). Keeping \(O(v^2)\) gives \(t \rightarrow t+vx+\frac 1 2 v^2t\), which is the correct expansion of the full transformation to the second order. Now, taking \(x \rightarrow x+ \delta x, t \rightarrow t+vx\) gives by the similar calculation \(x \rightarrow x+vt+\frac 1 2 v^2x\). Is it what the exercise means?