Everything posted by taeto

-

Corona virus general questions mega thread

Sorry to be a stickler for wanting to know what words mean 😉.

-

Corona virus general questions mega thread

Thanks a lot Kart! Ah, so I see the term is 'viable', not 'alive'. A typing exercise for a new intern perhaps 🤔.

-

Corona virus general questions mega thread

Very curious about the title of that link. So the virus lives for a while, then it dies? When is it pronounced dead? After losing an envelope? Or its own capsid? What kind of 'air particle' does it inhabit? Does it need protective cover, or is it possibly just its own 'air particle' like a tiny dust grain? Similar questions for 'living on a (hard) surface'.

-

How to define arc of definition?

Dear това́рищ Dima, thank you for your praises! Unfortunately I suspect that such a special arc cannot exist. Referring to my diagram in the preceding post, I have tried to look at the case of the two lines defined by \(t = \pi/6\) and \(t=\pi/3.\) I calculate that they intersect on the \(y\)-axis only if \[\frac{\alpha}{\pi/2} = 1 - \frac{4(\sqrt{3} -1)\cos \alpha}{6(2-\sqrt{3})\sin \alpha +3}.\] (If you prefer to calculate in degrees instead of radians, the only change is to replace \(\pi/2\) by \(90.\) ) But when I plug some values of \(\alpha\) into this, it always seems that the expression on the right side is a larger number than the left side value.

-

How to define arc of definition?

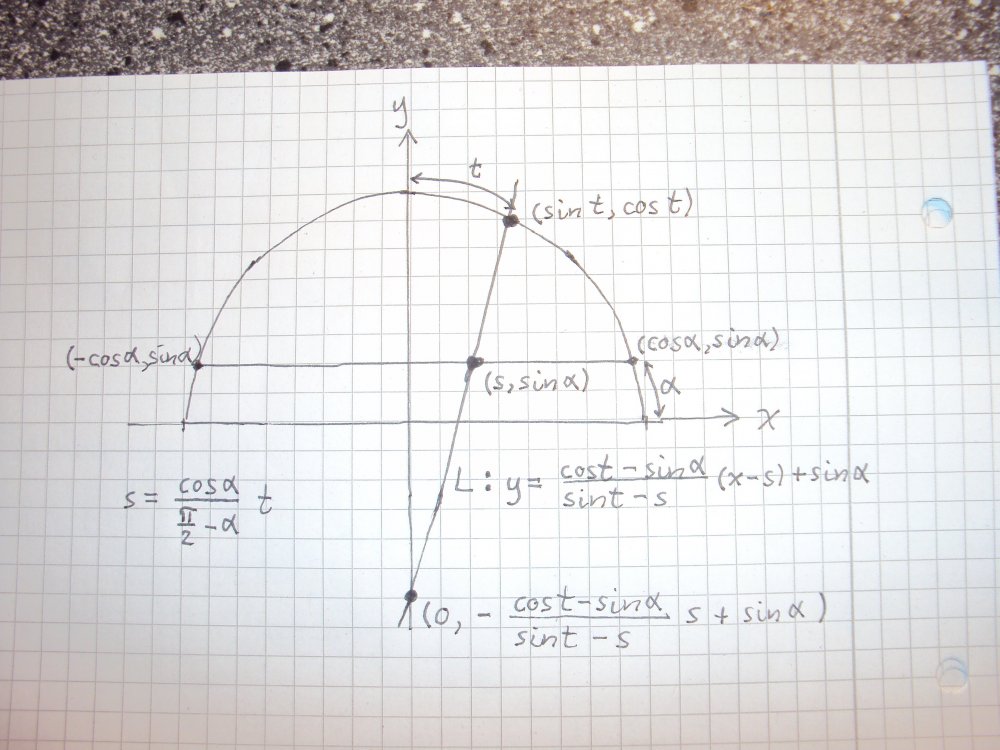

Then let us say that the arc has length \(\pi - 2\alpha\) and is placed symmetrically around the \(y\)-axis as in this diagram. Then the arc itself is the segment of the circle between the points \((\cos \alpha,\sin \alpha)\) and \((-\cos \alpha,\sin \alpha)\) in the upper half of \(\mathbb{R}^2.\) And its chord is the horizontal line segment connecting its endpoints as shown. If we take a random point \(p=(\sin t,\cos t)\) in the upper right quadrant, i.e. the point for which its distance to the \(y\)-axis along the arc is \(t,\) with \(0 < t < \pi/2,\) then the line defined by this point is the line \(L\) through \(p\) and the point \(q=(s,\sin \alpha)\) on the chord, such that the ratio \(s/\cos \alpha\) of the distance from the \(y\)-axis to \(q\) equals the ratio \(t/(\pi/2-\alpha)\) of the distance along the arc between the \(y\)-axis and \(p\) itself to the entire piece of arc in the upper right quadrant. So \(s = \frac{\cos \alpha}{\pi/2-\alpha}t\) follows. The equation for \(L\) becomes \(L : y = \frac{\cos t - \sin \alpha}{\sin t -s}(x - s) + \sin \alpha,\) which is checked by setting \(x = s,\sin t.\) Clearly the \(y\)-intercept of \(L\) is the point \((0,-\frac{\cos t - \sin \alpha}{\sin t - s}s+\sin \alpha)\) by setting \(x=0\) in the equation for \(L.\) If this is correct, then the question seems to be whether there exists a value of \(\alpha\) with \(0 < \alpha < \pi/2\) for which this intersection point does not depend on \(t.\)

-

How to define arc of definition?

Your diagram shows a sensible interpretation of Dima's construction. But it does not seem to say anywhere, nor is it made clear from the diagram, whether the lines are supposed to intersect in a common point. That part may have been something that I inadvertently invented.

-

How to define arc of definition?

If my interpretation is correct, then it is not possible that all the lines will intersect in a single point. If they did, the common intersection must lie on the line \(L\) defined by the midpoint \(m\) of the arc and the midpoint of its chord, which is the symmetry axis of the whole setup. If you compute how far down along \(L\) you find the intersection with another line \(\ell\), then you get an expression that contains nonzero terms with \(\cos t\) and \(\sin t,\) where \(t\) is the distance along the arc from \(m\) to the point on the arc that defines \(\ell.\) As well as it contains other rational nonzero terms that contain terms like \(t\) in their denominator. It is not difficult to see that if you differentiate w.r.t. \(t,\) then the derivative still contains such terms. There is no way that they may cancel each other out, hence the derivative cannot vanish. This means that the intersection points move around on \(L\) as \(t\) varies, in particular they are different for different pairs of lines. For the argument to be completely convincing, it would be better to calculate the precise expressions. But they get pretty complicated.

-

How to define arc of definition?

Thanks Dima, that is helpful; Спасибо! I stand to be corrected. But is the question anything like this: There is a special measure \(\alpha\) of a circular arc, with \(\alpha < \pi\), for which if you divide the arc of measure \(\alpha\) into \(N\) equidistant points, and you divide the chord between the two ends of the arc into \(N\) equidistant points, for any \(N > 0,\) and the line \(\ell_n\) is defined as the line that passes through the \(n\)'th point on the arc and the \(n\)'th point on the chord, for each \(n=1,2,\ldots,N-1,\) then the lines \(\ell_n\) all intersect in a common point? Maybe I just misunderstand the figure that got posted by studiot a couple of times now.

-

How to define arc of definition?

That is impossible, since there is no nearest point. It would be like asking for the smallest positive number.

-

How to define arc of definition?

Then for every \(a \neq 0\) you can calculate an \(x\) and a \(y.\) Is there anything wrong with that?

-

How to define arc of definition?

It answers one question in the original post, is that not right? A little more formally one would state that an angle is a congruence class (instead of "shape") of arcs of the unit circle. Does the original question about definitions of trigonometric functions still need an answer?

-

How to define arc of definition?

Dima has been courteous enough to explain some of his use of language. He said earlier that he does consider an arc to be a (connected) piece of the unit circle, and that he identifies the essential property of an arc to be its length. He considers arcs "modulo rotation" so to speak. Thus the use of language such as "the arc \(\pi\)" is unambiguous. We know by definition that the entire unit circle is the arc \(2\pi\). Therefore it makes no difference to speak of an arc which is \(1/n\)'th of the whole circle, and an arc of length \(\frac{2\pi}{n},\) for any \(n > 0.\) What gets a bit murky is how then it can make a difference how to "define an arc", when it is just the same as a real number between \(0\) and \(2\pi?\) Is the question really about how to define the various trigonometric functions? What we would answer then is that if \(\alpha \) is a real number in this range, then \(\cos \alpha\) is the \(x\)-coordinate of the left endpoint of the arc \(\alpha\) when it is positioned so that its right endpoint is \( (1,0). \) And so on, to define the functions \(\sin,\) \(\tan,\) \(\cot,\) etc. Or is it about something else entirely?

-

How to define arc of definition?

Every real number has a "non ending" representation in its decimal expansion. E.g. the standard representation of 1 is \(.999\ldots\) in base 10. You want to refer to the property that \(\pi\) has as opposed to rational numbers, that its representation is "non repeating".

-

How to define arc of definition?

Sure, segment is fine. I do not want to start an argument either. Just make the point clear whether we are going into real numbers or not. In basic geometry it takes a few steps before you get to Archimedean and even Cantor-Dedekind properties. It seems to me that Dima wants to discuss at the level of measures of angles and real-valued trigonometric functions, which is many levels away from talking about arcs and angles.

-

How to define arc of definition?

Not really. If we want to be painfully clear, then we should distinguish between what is an "arc" and what is an "angle", and your site does not seem willing to do just that. The page certainly does not like to consider that an arc is just a bunch, each with a particular property, of points taken from the circle, which is the view that I intended. Angles define some special kinds of arcs. If you have two straight lines through the origin, you have angles that partition the circle into arcs, usually four of them. Each angle defines a separate arc. There is no involvement whatsoever of real numbers yet. So you should explain the need to introduce real numbers in the first place. They seem largely irrelevant to the introduction of these terms.

-

How to define arc of definition?

I do not understand why you say that an arc is "very complex". If we already agree about what is the unit circle, what is difficult about saying that an arc is a certain piece of the circle? Are you aware of the difference between an "arc" and an "angle"?

-

How to define arc of definition?

But even without knowing the trigonometric functions and their inverses, is it not possible to still understand that an arc is a connected subset of points of the unit circle?

-

How to define arc of definition?

What do you mean by an "arc" when you say "there is especial arc"? An arc can mean a piece of the unit circle, or just an angle, in the context. Like, there is an arc from \(0\) to \(\pi /2\) and an arc from \(\pi\) to \(3\pi /2,\) or do you think of them as just the same arc, of length \(\pi /2\)?

-

How to define arc of definition?

Well, yes, well done! The OP seems to have in mind some kind of riddle, to which the solution is an angle between \(5\pi /6\) and \(17\pi /18.\): ...there is especial arc in which if to connect any two points of proportional division of this arc and its chord by straight line and to connect any two points of any another proportional division of this arc and its chord by another straight line , then the straight lines cross in one point of definition of trigonometric functions and angles(arcs). Scratching my head to figure out what it means.

-

How to define arc of definition?

Maybe it also helps to answer the OP's question to observe that the link given by Strange refers to a basic definition of an angle as a union of two rays that meet in a point. There is nothing about real numbers or approximations. The \(\sin\) function is then defined by assigning a congruency class of line segments to each congruency class of angles. Other explanations, more popular nowadays, are derived by assigning real-valued measures to angles and line segments. But the original definition needs none of that.

-

The Official JOKES SECTION :)

A cute Persian cross kitten.

-

The Official JOKES SECTION :)

OK, I'll reconsider. If she was 18 at the time of the photo, that might yet give the brows enough of a chance to get their act together.

-

The Official JOKES SECTION :)

Not enough unibrow for my taste, so I have to pass .

-

Infinitesimals and limits are the same thing

Thank you! And you agree with my attempt at reformulating the predicate "\(x\) is infinitesimal" as \( x\neq 0\) and \(n\cdot |x| < 1\) for all \(n\in \mathbb{N}?\) Is "\(n\) is standard" a predicate for a natural number in this theory? If so, you could also imagine to quantify only over standard natural numbers. My motivation for asking this: so far as I know, there is no first order theory for integer arithmetic that has only the standard integers as its model, and which only has finitely many axioms. Now supposing you can formulate "\(n\) is standard" as a first order predicate, it would seem that you could make a complete first order theory of the standard integers just by adding this single new axiom to Peano's finite list. Other than that, I appreciate your point about \(f\) not necessarily having a limit since it isn't standard. Do you know whether it has a limit?

-

Infinitesimals and limits are the same thing

Maybe it is only my confusion. Earlier you pointed to the role of hyperreals and the transfer principle. When you begin reading the Wikipedia page on Hyperreal numbers, there is no mention of logic until you reach the remarks on the transfer principle, in particular where it states "The transfer principle states that true first order statements about R are also valid in *R." Now, if the theory of *R were itself a first order theory, then I do not understand the need to invoke the transfer principle. I take it to mean that the theory of hyperreals, and by extension, that of infinitesimals which is derived from it, is a second order rather than a first order theory, even though the wikipedia page does not seem to state it explicitly. I have to be careful when reading statements about "completeness", because the notion of completeness of a theory, in the sense that every true statement has a proof, is also of relevance in this context, and perhaps even more so than the competing notion of completeness of the real ordered field itself.