-

Posts

4399 -

Joined

-

Days Won

49

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Everything posted by joigus

-

I think after a while one develops an intuition for when a poster is waiting for the right moment to unpack the real message.

-

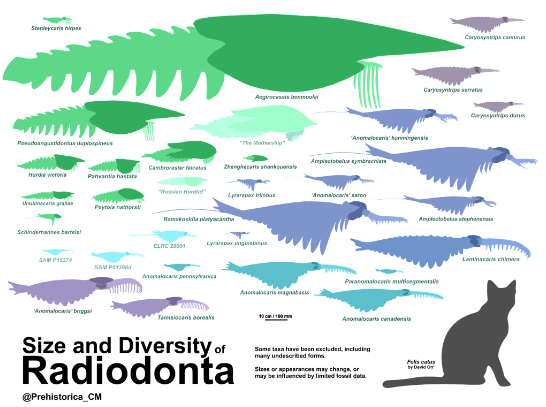

It's quite irritating when people just ignore your answer: Punctuated equilibrium? Introns, regions of DNA where exploration of possibilities can be afforded only by eukaryotes? I'll use bold for those particular points you seem to have difficulty with: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/earth-and-planetary-sciences/punctuated-equilibrium#:~:text=“Punctuated equilibrium is the idea,by intermittent bursts of activity.” Gradual, of course, is not absurd. We see it all the time. We see it in the bones, in the teeth, and so on. The "substance" you're looking for is, perhaps, alternative splicing. Or at least that's what some of those clueless scientists seem to have guessed at: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrg2776 Introns develop long, long before they are used against the environment. Most of these introns are lost, because they are no use. Every so-and-so many tens of millions of years, one of these intron rarities, happens to be useful for a specific environmentally-related purpose. When this extremely rare event happens, it manifests in the fossil record looking so similar to a miracle that only an expert could tell the difference. That's why having super-redundant eukaryote DNA is such a blessing in evolutionary terms. These "bursts of accelerated evolution" have been identified, studied, and at least partially understood long, long ago. Science is always a work in progress, of course. Fossils don't provide a movie of evolution for us to watch. Discontinuity of the fossil record was already observed by Darwin. Gee, I think somebody's mentioned it here too, Not long ago, we thought anomalocaris was really anomalous, a rarity of the Cambrian seas. Here's the picture now: Do you seriously think mountains don't grow only because you don't see them grow in your lifetime?

-

Gap? What gap? What god? There are about 5,000 If I were to make a guess, I'd say they are 5,000 different fantasies.

-

Sorry, my bad. If we did the impossible, what would be possible?

-

You mean like a biblical helping hand? Something like... https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theistic_evolution ?

-

Again? Sorry, you said we can a few times. Doing a gauge transformation has nothing to do with collapse of the wave function. They are very different things for many reasons. Mentioning gauge invariance was meant to argue that the wave itself is ambiguous in its definition (gauge ambiguity). A further reason why we can't measure it. Well, not of what's seen. Of what could be, if somebody took notice, happend to be there, or came later and checked. You can rest assured when the tree falls in the forest it does make a sound, even though nobody's there to hear it.

-

We can't "measure the wave." We can use the postulated wave to predict the measurements. The measurements are those dots on a screen. In fact, there is a theoretical principle, called "gauge invariance" --of which we're pretty certain-- that says there's a big chunck of this wave we cannot know in any way. Some people say it's junk, or a redundancy, etc. And black holes are not "dark-matter stars", but that's another story.

-

What are the benefits of understanding our free will?

joigus replied to dimreepr's topic in General Philosophy

Ah, but @geordief had already covered it: I was dealing with the "vice versa" version. So is this the essence of the compatibilist approach? That volition is emergent, or epiphenomenal, and it is every bit as non-delusional as temperature, or language, even though (or precisely because) it doesn't need to rest on a (hypothetical) micro-determinism? There's a mouthful! -

What are the benefits of understanding our free will?

joigus replied to dimreepr's topic in General Philosophy

This idea of "inclined to do" is another interesting fork in the pathway of analising the free-will problem. Is that what compatibilism is about after all? It reminds me of this idea of propensities in quantum mechanics. Is it due to Karl Popper? I think so, but not sure... It goes like, Alice has a very high chance of doing such and such, because she has a strong propensity to it. So that, say, 90 times out of 100 she will do it. The other 10 she's won't (under same circumstances). Is she 100% free 10% of the time? Or is she 10% free 100% of the time? By this perhaps I mean I'm not sure about these questions unless I have a good working definition of it. A point that's come up before on this thread. Your "miscalculation" statement reminds me of one time I thought maybe the whole question of free will is an ill-posed problem in the first place: Volition must be defined in terms of an action according to an intended result. Do we have any hope of squaring both at all? Everything we do is based on more or less blurry predictions of what will happen. Let me just agree with that. In that sense, what matters is a workable definition of when people cant adopt decisions in a way that's balanced, fair, law-abiding, and so on; as opposed to when people are acting under strong urges, biochemical impulses, contextual or biographical determinations, past trauma, etc. Easier said than done, of course. -

What are the benefits of understanding our free will?

joigus replied to dimreepr's topic in General Philosophy

Sorry. I was in a hurry. I meant: You did a bad thing => You did it because you chose to do it ("free will" for you) I did a bad thing => I did it because I had no choice ("determinism" for me) That's the double standard I meant. Does that make sense? I've got to get up to speed here, really. I missed much stuff. -

What are the benefits of understanding our free will?

joigus replied to dimreepr's topic in General Philosophy

Ah. The vice versa has interesting ethical consequences. A blatant double standard that one sees quite often. -

What are the benefits of understanding our free will?

joigus replied to dimreepr's topic in General Philosophy

Hello. I mean once they've happened actions seem like they were bound to happen. At least more than they seemed to be before they happen. -

What are the benefits of understanding our free will?

joigus replied to dimreepr's topic in General Philosophy

Interesting notion. What's outside that box? Nothing? The unreal? The unnatural? Nice. "Guess what. I couldn't help myself. I finally ate it! And I made another one, because I always wanted to have my cake and eat it too. I knew it all along. And what's more... I think I understand why I always do that." (determinism again... Or the illusion of it?) Maybe free will and determinism are about time frame. Does that make sense? -

Ok. Now it's perhaps the time to remind you that my observation wasn't at all about koalas. It was about how something can be named some way (eg, the observer effect) and actually the concept once clarified, not having anything whatsoever to do with the initial conceptual handle that nevertheless survived in the name. Examples: Koala bear (not even remotely a bear) Observer effect (someone actually observing anything not even remotely necessary) Long live both, koala marsupials and environment-induced decoherence!

-

Nobody is totally satisfied. There's a little Mick Jagger in me crying out for total satisfaction. It's the same kind of dissatisfaction that I've seen in the likes of Weinberg, Gell-Mann or G. t'Hooft for example. Although back in those times (before Gell-Mann wrote The Quark and the Jaguar, for example) it wasn't very fashionable to ask that kind of question. My way of putting it is actually from times long, long before I had any inkling that all of these great physicists felt a similar discomfort, and it can be phrased as, "What is the physical variable that tells me I am in this branching of the universe and not in the other?" You see, I can accept that there are amplitudes flying about corresponding to the dead cat of which I'm seeing the living version. But there should be a variable of some kind telling you: It's this one. Entanglement is not enough, because entanglement irreversibly separates the alternatives, but does not confirm either one of them. Ok. Now I suppose you're either from Australia or a neighbourhood close to a zoo with very poor security. I meant "observer effect" is a misnomer. Probably a mild one. It's the apparatus that does it. Not consciousness. I'm sure @studiot meant this: Duly noted.

-

OK. To be more precise. It shouldn't be about observation. I should be about interaction. Let me put it this way: It is as much about observation as it is about interaction. There's no reason to think observation cannot be understood in terms of interaction. The very reason --whatever it might be-- that we still have to say "when we observe, measure, interact with... the particle, it goes this way" is a sympton that even though everything works for all practical purposes, there is something we would like to understand better. Some of us, anyway.

-

And a koala is also called "koala bear" even though it has nothing to do with bears. It's a marsupial. That would lead us into the fascinating world of misnomers. The loss of coherence that connects the quantum domain with the classical domain has to do with interaction, not with the observation of anything. There are planets out there that nobody will ever visit, and electrons, protons, etc, are doing their business giving rise to physics that a potential observer would interpret as classical, because they are in the classical or quasi-classical regime. Again, it's not about observing, it's about quasi-classical interactions. Ok. I have no doubt now you've picked this up from somewhere, so I've been looking it up. A minority of people seem to use that distinction "passive" vs "active". Not that it has aroused much interest at all. It seems to come from D. H. Zeh in connection with the Everett interpretation. The rest of the community doesn't seem to be paying much attention to it. I'm certainly not. I don't find such distinction useful. It's only people paying heed to the many-worlds (or relative-state) interpretation of QM that seem to find it necessary. And, then again, not all of them. You should. The interaction Hamiltonian depending on the coordinates of the apparatus had better commute with the observable it's measuring. Otherwise it's just smearing things out. If it does, it can't change the statistical weights. If it doesn't... I've reviewed this over and over and over... And over. And what's inescapable is that it doesn't change the weights (the diagonal elements of the density matrix). But it does change (and how!) the non-diagonal elements of it. And guess how we call the non-diagonal elements of the density matrix. Yes, you guessed it. "Coherences". And that's no misnomer: It contains all the possible interference terms. If the interaction is "classical enough" (the mechanical action of order many times \( \hbar \) ), then the interference terms die out in ridiculously short times. So yes, in these cases the apparatus does something on the quantum system. And viceversa. But it's very different to telling us anything like probability of cat dead = 1 and probability of cat alive = 0. Superpositions should live forever. Now, there's a series of paths you can take from there, but I'm afraid they all involve some kind of semantic orgy I'm not willing to get involved in: Pick your alternative (many-worlds, double solution, transactional,...) and adhere to the litany the "natives" use. Not for me. I prefer to say, "I don't know". Amen to that. Except the bit about "observation". Ditto. Measurement in the formalism of QM selects a basis, not a state from that basis. I disagree. There are better alternatives, but they haven't been considered nearly as seriously as they deserve. But that's my view.

-

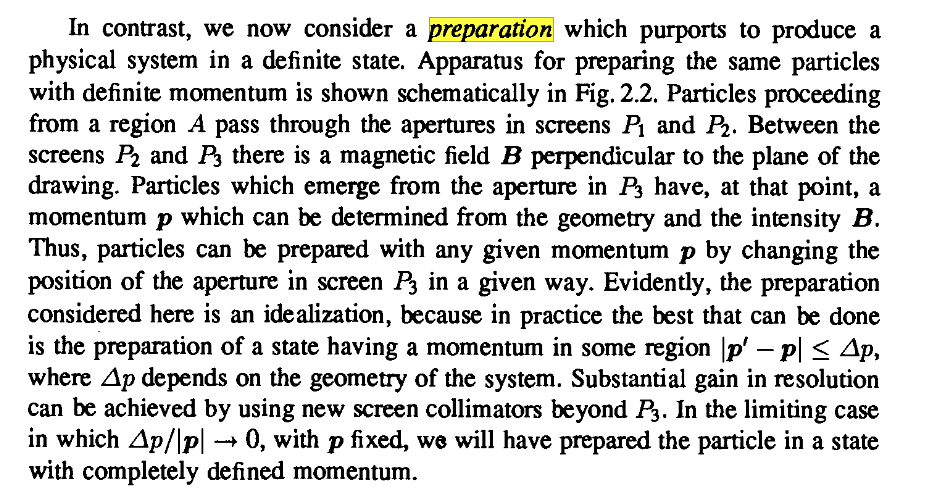

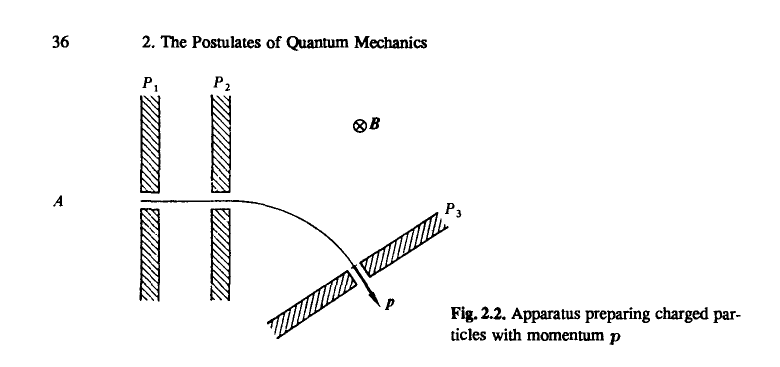

One of the good things about having these discussions online is that nobody will end up too wet. Please substantiate How much maths am I allowed to use? Schematically coherence in a state is a precise match between 2 alternatives embodying distinguishable results (mutually orthogonal): ψ1 and ψ2 . These states being coherent means that there is a very steady correlation between their oscillatory states. IOW, they oscillate in phase. These states usually involve preparation and can be mathematically represented by a linear superposition \( \psi=\) ψ1+ψ2. Before the rest of the universe interacts with our \( \psi \)-system, we can represent the situation by a wave function \( \left( \psi_{1}+\psi_{2} \right) \times \Phi \), \( \Phi \) representing the quantum state of the rest of the universe. When this system interacts with the rest of the universe so as to record what the microsystem \( \psi \) is doing, broadly speaking what happens is that the rest of the universe (environment, measuring apparatus, any friends watching it all, etc) records it by means of some macroscopic recording states \( \Phi_{1} \) \( \Phi_{2} \) while getting entangled with the quantum system: \( \psi_{1}\Phi_{1}+\psi_{2}\Phi_{2} \). These states are suposed to be semi-classical at some level of amplification, which means that while all this is happening, they oscillate in a crazy way so that the different components of the microscopic wave function can no longer "read" each other's phase. Please substantiate! when does it and when does it not! Preparations do not involve decoherence. You just filter the state that you want, and the salient state has certain controlled values of their physical parameters. Typically it involves momentum and/or spin: (from Galindo&Pascual, Quantum Mechanics I, a book I do not recommend to learn quantum mechanics, and has probably been outdated.) I hope that helped,

-

-

OK. Thanks very much. Again, one thing I've noticed is people spending considerable time explaining how they interpret this interpretation. You, for example, introduce distinctions like observers playing "a passive role", as opposed --I assume-- to an active role. Now, I don't know what that means, or how is that supposed to be a part of the physics of it. I don't know how to include that in the Schrödinger equation either. Perhaps you mean the quantum system doing something on the apparatus, but the apparatus is doing nothing on the quantum system? You go on to remind me that it's not that we need observers, but that we are observers. Well, again you seem to insist on the old misguided concept of observing, as if it were some kind of distinct physical influence. Never mind "needed" or "existing" (inevitable). I suspect it has to do with your distinction active/passive. But we know it should not be about observing anything; unless it can be explained in terms of interacting with the system in a certain way (a way that involves decoherence between the salient components of the state). These components involve a perfect correlation between certain macroscopic states and their corresponding "measured" microscopic states. If you are happy with physics providing you conditional probabilities (in the quantum version, conditional amplitudes), then it's ok. Quantum mechanics is linear and unitary. The combination of both aspects gives you, quite unambigously, a macroscopic universe that is "contaminated" of splitting alternatives. What, in the mathematics of it, tells me I am the observer that sees one (and not the other)? In other words, what physical variable is the one that tells me I'm in one of the components of the relative state that speaks of conditional probabilities? You can ask this question over and over to people who abide by this interpretation, or any one of the manifold versions of it, and all you hear is what to me sounds like "let's not talk about that". That's why I'm not totally satisfied. Are you?

-

You can't split up a proton in the usual sense, as a proton is a bound state of quantum chromodynamics, and its "constituents" (quarks and gluons) cannot fly apart as such, but only form further particles. But they weren't in the proton before the collision, and some of them are similar to the proton itself. It's said that quarks are confined. So it's kinda like as if you try to split up a PC and, as a result, you get a bigger PC, a laptop, and a tablet. Those are not "parts" of what was there before. As to how much energy you need, the minimum is the rest energy of the particles you want to produce. If you want to split the quarks apart the answer is easier: infinite energy.

-

I was just quoting you: You seem to be interpreting an interpretation. I understand your predicament. It's not easy to make sense of it in your mind. In your answer it seems clear that you invoke the observer in order to distinguish the alternative that comes out of the measurement: But why do many observers agree upon the same alternative having been realised? Why do these multiple observers all get split into the same "congruence of observers" seeing the same thing? Why do you need an observer? I don't see any strawman in showing dissatisfaction with that state of affairs. I'm not aware that the many-worlds interpretation (orthogonal worlds interpretation if you'd rather call it that way) has made much progress in any direction except to ease the minds of some of the uncomfortable ones. Oh, don't worry, all the observers that disagree with us all have gone into an orthogonal alternative congruence of observers. I'm still uncomfortable, perhaps that's all I can say. Along with the confession that perhaps I haven't interpreted something essential in that interpretation either.

-

The problem, to me, is that we have to spend time discussing how to interpret an interpretation. The least an interpretation should be asked to do is to dispell any need to interpret the interpretation. Also, personal views should be not necessary.

-

Thank you. Yes, I'm familiar with it but it's not falsifiable, so I don't consider it an explanation of what I want to understand. Invoking a new universe every time a leaf makes a ripple on a pond is what I would call an ad hoc explanation.

-

Right. I missed that one. Would you care to elaborate, please?