Posts posted by Butch

-

-

Edited by Butch

9 minutes ago, joigus said:But this hypothesis is manifestly incomplete. You assert something can be constructed, and you do not provide even the faintest idea of how this construction can proceed. So the obvious follow up question to your 'hypothesis' is,

How?

On the contrary, Fermat's principle, is either true or false experimentally. It makes no constructive assumption. The time is either minimal or not. There are no shady areas in that statement.

Well I have described the how of a photon... I am seeking charge. There is much between here and the "standard model". You do not have to agree with my hypothesis to explore possibilities, in fact to do so would be foolish. Perhaps you have a bit of time to take a positive outlook, just for giggles?

And as I have stated, charge would be represented by a persistent phase shift.

-

-

My entities have no inertia, they have no mass... the apparent mass of my entities is the combined gravitational influence of every other of these entities in the universe... the gravitational field. Any properties that I am able to discover via my hypothesis will be properties of the gravitational field, not my entities. Charge will produce particles that my entities are a constituent of, but the property of charge will be evidenced in the gravitational field produced via my entities in a system of inyteraction.

-

Edited by Butch

1 hour ago, Butch said:Field degrees of freedom exchange energy via couplings. The reason we say that is that there's a precise mathematical definition to hypothesize it; and methods have been developed to check the predictions.

My model has just 3 entities coupled via 3 lines of force, I have joined 2 ("ac" and "bc" to demonstrate the influence of the system "ab" on "c". The mathematical definition you speak of is also to be applied to a limited system to produce usable quantities, it could be applied to the whole of the universe. My hypothesis is no different, the couplings are there, the degrees of freedom also... The tripping point is that this hypothesis ventures to the extreme micro, the exchanges of energy are predestined, as my entities comprise everything.

By the way, as "ab" returns to quiessence the system "ab" and "c" would relocate, this relocation would affect the neighbors who would affect the neighbors etc./time.

29 minutes ago, joigus said:That's not how science works. If you want to have people consider your new concept, first understand all that's been already understood. Doesn't seem like you really understand inertia, gravitation, and their intimate relationship; or 'quantum' vs 'classical', or chirality/helicity, or gauge charge. You want to build physics from scratch, and there's no change in the world that this will ever work. If you think it will, as Swansont said, make a prediction, or a derivation of some long-known feature.

It is here, observe the photon model I have presented, it is a wave packet and more, this photon would have influence on the entire universe as the lines of force between "ab" and every other of my entities in the universe, there will be "interference" as this wave propagates, and as far a "c" is concerned it would be a variance in strength along a single dimension. It will be this way for all of existence. That is imperical evidence that goes back to the very youth of physics.

The sum of the energy propagated from "ab"? Zero! Before the energy was propagated by "ab" it was received by "ab" and is being propagated not just by "ab" but the entire universe. All the math and models work here... what is missing is units. Before we have units, we need to find properties and relate them, then we can connect to existing theory. I am not trying to rewrite science.

And please keep in mind, the only property my entities express is garavitation... all other properties are expressed in the gravitational field.

37 minutes ago, joigus said:Neither Einstein, nor Copernicus, were fools on a hill. They were very knowledgeable about the status of physical theories at their time. All experiments are limited, of course. Do not ever trust any statement that represents itself as unlimited.

The Beatles "fool on the hill" saw the sun going down, but the eyes in his head, saw a world spinning 'round... quite a leap at the time, the kind of leap that could get you killed.

53 minutes ago, joigus said:No. Inertia is locally indistinguishable from the gravitational field. (Equivalence principle.)

I am speaking locally concerning my entities, they have the property of gravitation which produces the gravitational field.

-

53 minutes ago, Butch said:

Do you comprehend the idea that properties other than gravitation are expressed in the gravitational field, rather than in the entities, it is a foreign concept, not a complex concept.

For example, if I can find a system state that manifests charge, then I will have a particle, an entity that is "solid" so to speak. The photon in my model is just an oscillation of the influence of pair "ab" upon "c" it is a packet because the pair "ab" will return to a near quiescent state rapidly(in terms of orbit count, perhaps in less than a single orbit, dependant on the strength of the disturbance). This is not EM, but we know EM exists, I just need to find it.

-

1 hour ago, swansont said:

you haven’t done science. You don’t have a model in any meaningful sense, and this is far from “unheard of”

True, one example of this type of leap is Albert in a speed of light vehicle.

2 minutes ago, joigus said:They don't have inertia? How come?

Inertia is a property intrinsic to the gravitational field, the combination of influence of the multitude of my entities.

6 minutes ago, joigus said:Field degrees of freedom exchange energy via couplings. The reason we say that is that there's a precise mathematical definition to hypothesize it; and methods have been developed to check the predictions.

In physics, you can't just utter a sentence and hope it will make sense somehow. Example: space-time gains acceleration via vacuum energy. Yeah right, but that responds to a mathematical model.

You haven't shown us a mathematical model, however crude. You have a motion cartoon and a bunch of intuitions.

True enough in the classical sense, but this hypothesis is at an extreme, discrete entity or field becomes a question of the chicken or the egg. In this case they both just are, expression of properties is evident in the field, not the entity.

13 minutes ago, joigus said:Field degrees of freedom exchange energy via couplings. The reason we say that is that there's a precise mathematical definition to hypothesize it; and methods have been developed to check the predictions.

In physics, you can't just utter a sentence and hope it will make sense somehow. Example: space-time gains acceleration via vacuum energy. Yeah right, but that responds to a mathematical model.

You haven't shown us a mathematical model, however crude. You have a motion cartoon and a bunch of intuitions.

I have introduced a concept, if you wish to contest it, first strive to comprehend it, then provide evidence against it... this is the critique that drives me. It feeds my endeavor, I need this from you.

19 minutes ago, joigus said:They don't have inertia? How come?

Field degrees of freedom exchange energy via couplings. The reason we say that is that there's a precise mathematical definition to hypothesize it; and methods have been developed to check the predictions.

In physics, you can't just utter a sentence and hope it will make sense somehow. Example: space-time gains acceleration via vacuum energy. Yeah right, but that responds to a mathematical model.

You haven't shown us a mathematical model, however crude. You have a motion cartoon and a bunch of intuitions.

That's not what I hear. LIGO's still active, ATLAS at CERN, James Webb Space Telescope, and so on, and so on.

Yes but they are limited. Even the macro is limited, how will we investigate what lies beyond the observable universe? I do have faith that we will be able to do so, but it will take leaps such as this, leaps such as Einsteins and much less obvious leaps such as Copernicus (fool on the hill).

2 hours ago, swansont said:You need to have a model and testable predictions

I do, unfortunately, I may not live long enough... My only hope is that others will comprehend this concept and do some of the work. Do you comprehend my entities? Do you comprehend the idea that properties other than gravitation are expressed in the gravitational field, rather than in the entities, it is a foreign concept, not a complex concept.

2 hours ago, swansont said:That’s not for you to determine

You are correct, just my opinion... I hope someday your opinion.

32 minutes ago, Butch said:They don't have inertia? How come?

Inertia is intrinsic to the field, not the entities. Changing the position of a single entity, changes the position of every other... given time, through the lines of influence that constitute the field.

-

1 hour ago, swansont said:

Why would it be infinite? Force is a vector, so an isotropic distribution will add up to zero; for every one at some distance and direction, there would be one at the same distance in the opposite direction

Yes, however if you change the momentum of one member of a system seeking quiescence, all resist... you change the entire system by changing one member, some members just get the news later than others.

The influence vectors are tensors, it is not evident in my model because it is static, with the exception of the orbitals "ab", however all members would have motion relative to all others (some quite complex), this motion would "bend" the vectors when travel time of influence is taken into account. I cannot demonstrate this with an accurate model yet, I have no units. This will have to wait on further devopment.

1 hour ago, swansont said:If all they are doing is exchanging energy with each other, the total stays the same. No decrease in temperature. As you say, these interactions are elastic, so there is no dissipation.

Some could combine into one, perhaps, but this would require others to have a lot of energy. It might be interesting to model how many could combine, and under what conditions, and for how long. If a high-energy entity comes along, it would break such a combination up.

They cannot combine or the universe would cease to exist... I do know of a way such combining could be prevented, it is simple... but I have reason to wait before presenting it. I will provide a hint however, the "big bang" and the "steady state" can co-exist... Hoyle ultimately is most correct however and deserves his Nobel prize.

1 hour ago, swansont said:It’s impossible to get my head around your contradictory claims.

They are not contradictory, you fail to distinguish between my entities and the field they ptoduce.

1 hour ago, swansont said:Why would there be gaps?

Gravity is now undetectable?

Influence vectors are 1 dimensional, tensors are 3 dimensional with a 1 dimensional cross section, a finite number of them cannot fill 3 dimensional space... an infinite number can.

-

Edited by Butch

1 hour ago, swansont said:Pull? Do you mean a force? How can you have a force on an object that does not resist a change in momentum?

How do they shed energy to get to (or approach) absolute zero?

They do resist change in momentum, in an infinite universe(which is the way I lean) you would be pushing against an infinite amount of force, fortunately it is an elestic collision (again, thanks to c) in a finite universe you would be pushing against a finite resistance. However, as I have said, these are human terms, all this pushing and pulling was predetermined.

They exchange energy via the gravitational vectors(I still believe at some point they can be shown to be tensors). The only way energy could be shed is by a combination of multiple entities into one, or by reaching a quiescent state where there is no longer any momentum anywhere... if it where not for light speed the universe would attain absolute zero instantaneously, however since there is speed to light, Hoyle deserves his Nobel... (something for you to ponder).

1 hour ago, swansont said:Pull? Do you mean a force? How can you have a force on an object that does not resist a change in momentum?

How do they shed energy to get to (or approach) absolute zero?

How can one piece together you model when you keep posting contradictory information? They do not resist a change in momentum, but there is a resistance to a change in momentum. You can’t have both.

I remember you asserting this, but not where your model shows this.

When things are A but also not A, that makes comprehension very difficult.

I agree, but I believe nature has fooled us. Try to get your head around it, but don't be in a hurry... let it sink in, or you will experience that strange buzzing sensation, that indicates overwork.

1 hour ago, swansont said:How can one piece together you model when you keep posting contradictory information? They do not resist a change in momentum, but there is a resistance to a change in momentum. You can’t have both.

The resistance to a change in momentum is intrinsic to the gravitational field, it occurs because influence between the entities travels at light speed. If it was instantaneous, the universe in unison would push back with equal force instantaneously, as it is, it pushes back proportionately to the strength of the gravitational field/time.

1 hour ago, swansont said:I remember you asserting this, but not where your model shows this.

My model does not show this, my model was only to show that my miniscule entities could generate a gravitational wave at light frequency in packets.

My entities really are at the threshold of existence, it is better to think of them as a source of the gravitational field, the gravitational field is where everything is happening. My entities alone are nothing, really absolutely nothing... the only thing that makes them something is the gravitational field they produce.

Perhaps this will help, if there were a countable infinity of my entities, there would be no gaps in the gravitational field, every bit of it would be criss crossed by lines of gravitational force. If there were a finite number all that is the physical universe would be connected by those lines of gravitational force, there would be gaps, but they would be completely undetectable.

Or as far as my model goes, between a and b there is nothing, absolutely nothing, no particles... only the lines of gravitational force.

Comprehension is difficult because I have done something unheard of in science, I leapfrogged to an extreme, the micro extreme... It is a valid leap however, because our tools of observation are running out. My hypothesis may be wrong, but my method of developing it, is where we must go. If such a hypothesis is found to be correct, physics will need only proceed then to the macro, and it is my belief that is infinite... perhaps someday a leap must be taken there also.

-

Edited by Butch

1 hour ago, swansont said:And I’m asking how this happens.

If they are affected by all other fairies, then certainly they should be affected by one other fairy, and a fairy-fairy interaction could be described. You seem to start this already, with two fairies being described, but the next step is explaining what, precisely, is exhibiting the 1/r^2 behavior. It can’t be a force like in Newtonian physics, because these do not resist a change in momentum.

How does your model get to where they have an “effective mass”?

They all have equal gravitation (a force of attraction), they are all pulling on one another, seeking quiescence, the state where all are in a balance, this is of course is absolute zero... it is not going to happen(although it could if information were passed instantaneously, thank goodness for c) so the gel continues to jiggle and the universe goes on... Which brings up an interesting thought... Since my entities have only apparent mass, could 2 of them at some point have equal numbers? If they did, they would condense into a single entity and energy would not be conserved...

There is resistance to a change in momentum, remember apparent mass is a result of the gravitational field, not an intrinsic property of my entities, they have only gravitation. We perceive action and reaction, what is actually happening is an ongoing reaction we call the universe... but in human terms(which is not quite accurate) if you impel a single entity you impel them all, the resistance to change in momentum is the combined resistance of the entire universe... but in reality, cause and effect are just the ongoing jiggle of the gel.

As I said... comprehension and investigation, this is more difficult to comprehend than is obvious at first glance.

-

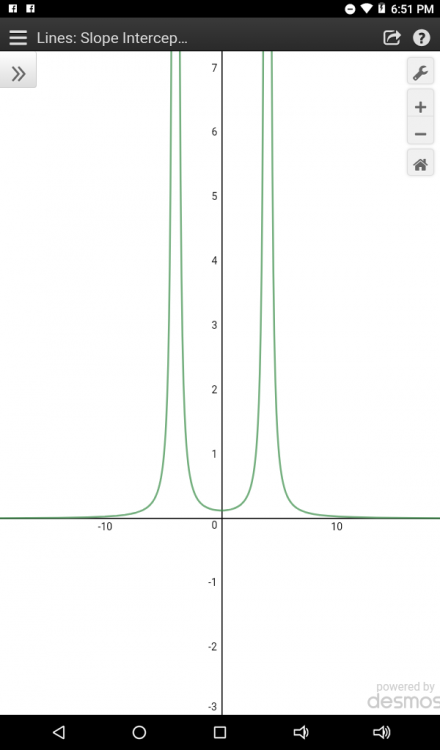

Nope, no joy... I do need an actual gravitational model rather than just a representation of influence... do not think I can accomplish this with desmos.

Just now, Butch said:Nope, no joy... I do need an actual gravitational model rather than just a representation of influence... do not think I can accomplish this with desmos.

Thank you for your time, I think our discussion is at and end for now. I hope I have at least stirred some interest.

You guys are awesome.

PM me if you have advice.

-

7 minutes ago, swansont said:

That’s not really an answer, and those curves don’t look like inverse-square functions

I will repost with math.

Mass as far as my entities are concerned is the concensus of all influence by all others in the universe... the entities do not resist change in momentum, rather the gravitational field created by all of the entities dictates their position. They have apparent mass, but they independently do not have a property "mass". If you could isolate one of my entities, it would be massless.

29 minutes ago, swansont said:Then how can your conjecture be falsified?

Only by comprehension and investigation. I believe you do comprehend now... You are certainly much more the physicist than I (I know, quite the understatement) perhaps you could find just a little time?

By the way, I did do a model with the whole of the system "ab" in motion relative to "c"... no phase shift due to framing.

Have you any idea where I might find a persistent shift in phase of "ab" using my model?

Ahh perhaps as an orbital?... I'm off to see the wizard! Again thank you all so much.

-

Edited by Butch

2 hours ago, swansont said:You could have led with this description

I thought I had sent you a link to my blog, I apologise... You are my favorite "cattle prod" on this site, I greatly value your critiques.

27 minutes ago, joigus said:Polarity is directional; charge is a scalar (it has no direction).

I did not say it had charge, just polarity... I try not to miss anything as I develop my model... I don't think trivial exists here.

2 hours ago, swansont said:Is there any evidence that electrons are composite particles?

Interesting, yes, it has multiple properties... mass I can accept, as in my model mass is a result of the gravitational gel, I mentioned earlier... Charge is an issue, however perhaps my "ab" pair will exhibit charge in my coming model, if so, it might very well be an electron.

2 hours ago, swansont said:What else does it depend on? Inverse square can’t be the only dependence. How does the gravitation get to be “very strong”

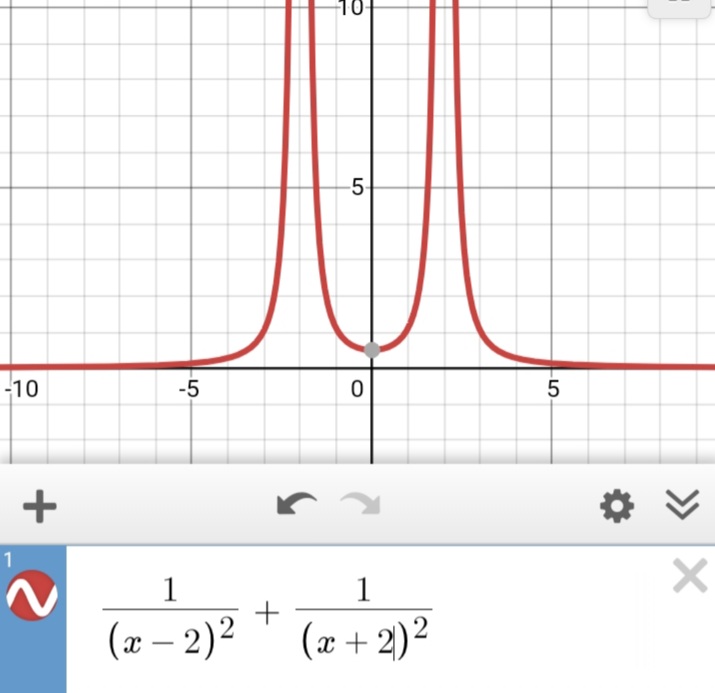

By the addition of two curves.

2 hours ago, swansont said:

2 hours ago, swansont said:How does time dilation figure into this?

Pure weirdness! Note in the pair "ab" no matter the eccentricity of the orbits (I have attempted to insert a slider in my desmos model for this, still working on that) an observer from "a" or "b" would "see" the complimentary entity remain at a constant distance, the closer they are the greater the gravitational influence and the slower time passes. Don't know that it has significance, but I don't want to miss anything.

2 hours ago, swansont said:They attract via gravity, which is inherently weak, yet inexplicably their gravitational interaction is very strong. They comprise particles that have no internal structure, but they are not themselves particles, and they have no properties but the particles they comprise do have properties. And the model you’ve shared explains none of this.

There is no strong or weak here, just gravity, the entities are not actually massless as they are constituents of that "cosmic gel" I have mentioned, but certainly their mass is minimal, so gravity may appear very strong, but strength... hard to define here other than how it relates to other parts of the model.

They are constituents which can never be detected, they are so primal that we will never have a hammer to hit them with, so if a particle is composed of a simple system of these entities, we see it as having no underlying structure... I hope however that you get my point that an entity with multiple properties, must have underlying structure.

-

1 hour ago, joigus said:

Scalars and vectors are particular (if trivial) examples of tensors, so don't worry too much about that. Every time you say 'vector' or 'tensor' to talk about an invariant or scalar, it makes your argument so much less convincing.

You should worry a lot more about how your model fits any known features of particles.

I still don't know what you mean by 'polarity'.

"ab" "c" is a vector it has direction and amplitude.

Yes, that is everything! "How it fits any known features of paricles"

As I have stated, I think the next big piece of the puzzle is charge. Is it possible charge appears with framing as a result of movement of the entire "ab" system relative to "c"?

Any orbit has polarity (right or left rotation). Whether or not this has anything to do with charge, I don't know at this point.

-

-

Edited by Butch

13 minutes ago, swansont said:But you said they don’t congregate there. Now you say they do. Why do they? Gravitational attraction? What is the mathematical form of this attraction? What does it depend on?

Are you just unwilling to share these details, or do you not actually have these details?

The part you are not getting is that any mass is composed of these entities.

I stand corrected in the use of scalar... the values used are relative, I have no defined units to work with yet.

The mathematical form is the inverse square, with of course time dialation... not expressed in my simple 2 dimensional model, it is worth noting however that within the system "ab" gravitation is very strong and time dilation is propotianate.

They do not congregate anywhere, they are where they are and where they will go is determined by the collective of all these entities in the universe.

Let me repeat, these entities compose everything that is the universe, they are the most primal possible a point source of gravity, nothing more.

A note, all I sought to introduce here is that a small enough system of gravitational entities could produce gravitational waves at light frequencies... most of the questions you have put to me I have already considered. Grandiose as they seem, I have simply begun my exploration at one end of the span of possible physics... the micro end. The entities I have presented are the most primal I could devise. They have no dimension, no spin, no mass, no energy, no charge, no polarity. All of that is in how they relate via gravitation. The model I have presented is nearly the simplest possible configuration... the pair "ab" being the simplest. I wish to build upon that, next I would endeavor to discover the manifestation of charge and EM. But first it is most important to me that you grasp this concept. I ill build a model with slightly more complexity for that purpose. Do not ask what the configuration is for any of the standard model components... I simply do not know at this point, with the exception of the photon, I believe I have that and will provide a better demonstration in my next model.

-

10 hours ago, swansont said:

If they are the source of gravity and gravity is stronger where we have mass, how can it be that they don't congregate where we have mass?

The greater the mass, the greater the number of my entities constitute that mass.

6 hours ago, swansont said:That doesn't answer the question

What does the strength of this interaction, between these points, depend on? Even if the strength is a free parameter, you have to have variables in the equation.

The strength of the entities does not vary, it is absolute and the same for all, I do not say it is infinite because the entity is a single point, gravitational influence is only evident as is relative to other such entities.

-

40 minutes ago, swansont said:

nodes of convergence"? More twaddle. What is converging?

The vectors of influence between each and every one of my entities, that influence is only gravitational and nothing else.

2 minutes ago, swansont said:What does the strength of this interaction, between these points, depend on?

What does the strength of this interaction, between a point and some particle of mass m, depend on?

All particles are a system of these entities, the values are scalar until they can be tied to the standard model, then we will have real units.

My next model will demonstrate the particle and wave nature of light... if you can grasp what I am trying to communicate it will also reveal the nature of c.

-

Edited by Butch

47 minutes ago, swansont said:Is there a mathematical solution for the motion of these points? Why do they move? What is the nature of their interaction with each other? Is it an existing interaction, or a new one?

It is the collection of all of them influencing every other, a cosmic gel constantly seeking quiescent. It is solely a gravitational interaction which produces every other... What we perceive as different types of interactions, different types of fields etc. are manifestations of these interactions. I am working on a model today to demonstrate one facet of this, I should have it complete by tomorrow.

47 minutes ago, swansont said:Does your idea work with, say, two points?

My idea encompasses the universe in its entirety, my model is local. My model is not perfectly accurate, because I cannot encompass infinity or the vast finite. I will be producing more models.

-

23 minutes ago, swansont said:

We already have the Higgs. That's been predicted theoretically and verified experimentally

Yes, and I followed with great interest... then it was discovered that it had colors... imo then it has underlying structure, the most primal entity cannot have multiple expressions, only a combination of those entities.

-

49 minutes ago, swansont said:

If they are the source of gravity and gravity is stronger where we have mass, how can it be that they don't congregate where we have mass?

They are the source of mass, mass is the overall influence of all of them. They are THE constituents of the universe.

52 minutes ago, swansont said:Influence...how? They move, according to your animation? Is this because they interact with each other? Is that a gravitational interaction?

Do they interact with matter, other than gravitationally?

The motion of each individual is a consensus of the influence of all upon each.

They are the only constituents of all matter. The influence vectors collectively is the gravitational field, mass is here, dimension, spin even polarity... what is missing is charge. I have a vague idea on that one, as systems of my entities have motion relative to each other a system such as "ab" may have a persistent phase shift via framing and that might be the charge of the system... I am looking for the tools I need to investigate this idea, perhaps because my mathematical proficiency is not great enough to do so, without such tools, if you would like to help... greatly appreciated.

Spin is rather difficult to explain and grasp... I will work on it. In the meantime, the spin is not apparent within a system, but rather as a result of the systems influence on the rest of the members in the universe.

To grasp this idea consider a universe consisting of nothing but the influence vectors (a countable infinity perhaps) and my entities being nodes of convergence of these influence vectors.

-

-

Edited by Butch

1 hour ago, swansont said:Is it a vector, though?

So why is the gravity from a more massive particle larger? Why do your particles congregate where we have matter? Or photons?

How can they travel with photons unless they are massless, but if they are massless they travel at c, so how can they be a part of matter?

A more massive particle would be composed of a greater number of these entities, remember they are single points... only an interacting system of them has dimension. They travel at a speed determined by the "i" of every other of my entities in the entire universe. The apparent mass is also determined by the same. They do not congregate where we have mass or photons... they are the most primal entities of our universe, they lie at the threshold of existence, they are all that our universe is.

They are not particles, they have no dimension, no spin, no wave function, only apparent mass... and gravitation. Influence one and you influence all.

And yes, an interacting system ("ab") has polarity, spin and wave function (when nudged, producing photons). I believe a more complex model would demonstrate that the "influence vectors" are tensors.

But what is "ab"? It is the most primitive system that can be built with my entities... is it a neutrino? An electron? I do not know at this point. "I" may never know...

-

-

Edited by Butch

Other than the spin issue, the point of conjecture with my model is that my entities are not carriers of the gravitational field, however they are the producers of that field... my model is simple, but consider a universe where my entities are the single primal constituents of all matter... a universe abounding with them in different configurations that result in the less primal constituents that we are aware of. The multitude of gravitational tensors would form for all intents and purposes a continuous gravitational field. I that so far fetched?

4 minutes ago, joigus said:Massive or non-massive. It's just that we don't know of any spin-1/2 massless particles.

Think of helicity and chirality as elementary-particle versions of the property of a corkscrew: Normal corkscrews are right-handed; if you rotate it in the clockwise direction, it goes downwards. Left-handed particles are like the corkscrew that you see in the mirror.

The area per unit time swept by the line joining a and b is the angular momentum per unit mass, and it's conserved (Kepler's second law). No mystery there, I guess.

What about time dilation? No mystery, but if you give it a moment of thought, quite interesting! Remember gravity at these single points is absolute... I hesitate to say infinite, because at the single point there is no relativity and if 2 occupy the same place with equal moments (I know... no mass) they would not be two.

.thumb.jpg.cc169fb67f9c969aeace623286b9b5e6.jpg)

What is "i"?

in Speculations

It is not clear, you need to look again... I will work on the tasks you have presented.

Also a persistent shift in phase of a closely interactive system would produce a field unique in comparison to the "normal" gravitational field... It would comprise an EM field. The photon would not be a member of this field, but it would be a close cousin.