Everything posted by tar

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Vampares, Ah but the strategic pen hole is mightier than the slice of the steak knife (sword). And its the rendering program that is not worth a wit, without a wit to wield it. Regards, TAR Mike, Maybe you could use that white paint to paint some center lines on the Grand Canary mountain roads. From space (Google Earth) it doesn't look like there are any mid lines. Anyway I am considering reopening the case, so that 3meter diamond might still work. Or perhaps we can do something with those odd shapes in Janus's last rendering. In any case, I am rather sure that my original "Janus" sections of sphere are exactly 12th of a sphere, each. Having both 1/2th the surface area of a sphere, and being exactly 12th the solid angle of a sphere, each. If you divide one of these, exactly down the middle, with laser rays, eminating from the exact center of the sphere, the remaining two peices will each be exactly 1/24th the solid angle of a sphere, and , the curved surface area of each peice will be exactly 1/24th the surface area of a unit sphere. It does not mater, whether draw the lines, exactly in half this way or that, or along this diagonal or that, as long as you are making the cut with a laser from the center and keeping the laser on the same plane, as you make the cut (a straight cut), there is no choice but to split the solid angle, and the surface area in half, with the same cut. Won't result in identical peices, but the peices will each contain the same elements of solid angle, volume and surface area. I would think. How could it be otherwise? Regards, TAR Janus, Problematic, indeed. The diamonds on the other hand, staying on surface, stay diamonds when you half them from the sides and not from the point. You always have a diamond to work with exactly 1/4 the size of the parent. And the halfing lines do some nice things, as I mentioned. On the first iteration, the new lines describe six big squares and eight big triangles, exactly in the pattern of cutting the corners off a cube, like we started the whole process with. Regards, TAR

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Janus, That is really interesting. Perhaps the four hexagonal planes (and the three square planes) at just those right angles to each other, conspire to equalize the vectors as Mr. Fuller noticed. Perhaps it really is as "magical" (meaning really really neat) a figure as I have sensed. Imagine what you did there. Cut twelve in 1//4s to get 24. Interesting indeed. On a parallel note, I was rethinking the cutting of the diamond into smaller diamonds. Granted it does not work so neatly if you are trying to make faces, but what if you stay on the surface? I remembered on the way home today, that when I drew my 48 and then 192 diamonds on my clay ball, I never broke the surface. The lines I was drawing where always exactly one radius away from the center of the sphere (cause they where on the surface). It is not a matter of figuring was surface area the shape is subtending, because its ON the surface and the area is exactly what the area is. In the case of the 192 diamonds, that would be 1/192nd the surface area of a sphere. Regards, TAR

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

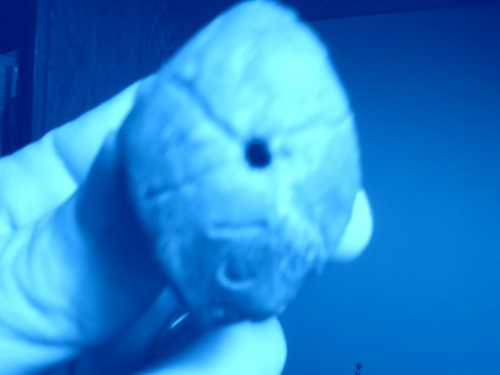

MD65536 and Janus, But wait. The diamonds forever are out, but you both suggested the diagnoal route to four triangular faces, from the diamond. I did a little diamond cutting, trying to cut the diamond face flat, while staying true to the internal angles and attempting to stay normal to the center of the sphere, and like Janus says, the vertices are not on the same plane, so you wind up with a "cut" diamond, looking a little like a 4 faceted jewel. Regards, TAR I cut that one a little too deep, not knowing what to expect. It appears, to stay true to form, the exact center of the diamond should still be there as the only point on the original surface. That, and the four vertices of the original diamond shape. So the diagonal lines, leaving four triangles seems like it is the way to go to 48 divisions. But it doesn't look like the pieces with be identical. They appear to be, like Janus said, mirror images of each other. Same dimensions and angles, but one shape is lefthanded and the other right. So of the four, the catty corners are identical to each other, but the neighbors are mirror images, along the diagonals. Don't know if you can split these guys in 4, or 2 or 3. Maybe I'll wait to see if this way to 48 facets, with all vertices on the unit sphere, works.

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Janus, Got it. I think my clay was too forgiving and the slivers could have fit anyway I wanted them to. Thanks for trying it out with real angles. Guess that brings the TaRadian to a screaching halt. If they don't divide into identical sections then the volume and surface areas can not be both 1/4ed with each successive division and the plan is poop. I was considering that if the solid angle at the center was quartered and the diamond shape was quartered, the interior angles would take care of themselves. Looks like I thought wrong. Anyway I really do appreciate you building out the ping pong ball arrangement, I have been trying to do that for a really long time. Still an amazing arrangement, just not as amazing as I was thinking it might be. Guess I will abandon the globe splitting quest. Without being able to reliably divide the solid angles in a manner that would keep the sections identical, there is no hope of using it as a measure of solid angle. Looks like we have the steradian for a good reason. Thanks again Janus. Was sort of exciting there for a moment. Regards, TAR

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Acme, I am working on the previous suggestion to try the divisions out on the globe. It worked out really nice in preparation, my globe was about a foot in diameter so I took 6 inch peices of tape brought on down from the North Pole on the Prime Meridian, another on the date line, and another two between. (looks like a cross from the north pole. Did the same from the south. From the ends of the tapes coming from the poles made the wide angles of the four diamonds running lengthwise around the equator by simply putting the one end of the 6in. piece at the end of the tape coming from the pole, and the other end of the tape on the equator. It made the perfect angles. I aborted my effort. I have to take new pictures, minding my lighting and distance from the globe on each shot, and be a lot more careful photoshopping my sections, but here is a "rough draft" beginning of substituting globe sections for the diamonds in my diagram. Nevermind. Its incomplete and lousy to boot. I'll post something when its presentable. Could be a while.

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Probably best to flip that diagram 90 degrees and put the four lengthwise diamonds along the equator, if one was to use it to divide up the globe, inorder to see the whole thing at once. Nice arrangement, as that it is not a projection, but an actual division. You could even leave the curvature and the terrain on a section, and it would still work to see the whole thing at once.

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

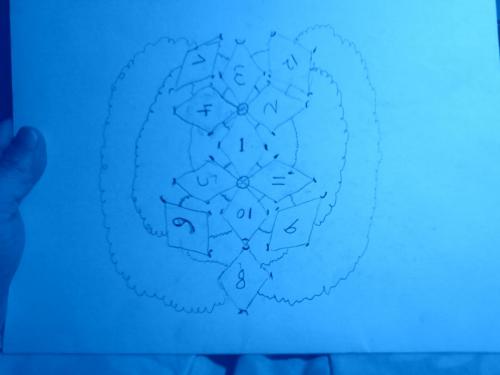

Imatfaal, I am just giggling rather hard at myself, having made 4 tetrahedron out of color clay balls and toothpicks and was in the process of trying to interlace them. I guess I am easily amused to find clay balls and toothpicks and my inability to sort out the pattern so hilarious. I took a picture, of the source of my amusement, which is definitely NOT your avatar arrangement yet. I'll post it in a bit. Just for fun. Regards, TAR ...WOW... Janus, You really have to do the cutting the diamonds in quarters thing. The new lines trace out the rhombic dodecahedron again. Or so it seems on my masacred clay ball. Regards, TAR well wait, not suprising at all. I drew the lines thru my pen holes. Duh. But I sure would like to see the Janus rendition of the resulting 48 sided figure. We could change the thread title into "dividing the sphere into 48 identical sections" Its neat. You can follow a pair of sides zigzaging all the way round the sphere and landing where you started. Then turn the big diamond 70.53 degrees (or 109.47 the other way) and follow pairs of sides around in the same zigzag. The only big diamonds you miss, doing this, are the two at the acute tips of your diamond. So you can follow pairs of sides around and see 24 little diamonds on each transit. The opposite big diamond (the opposite 4 little ones) you transit on both trips. The eight little ones off the tips of your starting diamond, you never transit following the pairs of sides around. Anyway, neat 48 sided figure, with some possibilities for further exploration. Sure would be nice to see that wireframe...(hint, hint) Here also attached it a first draft of laying the twelve sections of a sphere out where you can see the whole surface at once.

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Imatfaal, Was wondering a few things. Looking at your profile figure, I noticed the four points at the top frontish seem to describe a square and the two of these, along with a point on the left describe a triangle. Is your figure, the same arrangement as the cubic octahedron? It looks like it is made of intersecting tetrahedra, but I would be interested to know how it is put together. And after looking through this link on the cubic octahedron http://kjmaclean.com/Geometry/Cubeoctahedron.html with the vector equilibrium idea, and the fact that it fit more snugly into a unit sphere, than the cube, I was wondering if we could come up with a regular strategy, based on this arrangement, to derive a figure that fit even more snugly into the unit sphere. If so, it might be possible, not to square the circle, but to sphere the cube, and thereby derive a function whereby the increasingly small diamond shapes of the same ratio, would have, at each iteration an exact number of which would complete the figure. If such a function could be described, when taken to the limit, to its smallest integral, approaching an infinite number of sides/diamonds, of increasingly small dimension, but the same ratio of diagonals...we would have a function that could sphere a cube. Leading me to wonder if we could find Pi in the ratio of the diagonals of the diamonds derived and depicted in my original clay figure. Regards, TAR or perhaps, not that we could, but that we should be able to find Pi in the ratio of the diagonals Janus, Can you do MD65536's divisions in quarters of the diamonds, keeping all the vertices on the surface of the unit sphere? And then divide each of the resulting diamonds in the same quarters, again keeping all the vertices on the surface of a unit sphere? We might already have the strategy. Conceptionally use the TARadian, whose solid angle is 1/12 of a sphere's, and the surface area of a Janus section which is 1/12th the surface area of a sphere, and divide the section in quarters, which will simultaneously divide both the solid angle and the surface area into quarters. Regards, TAR

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

imatfaal, Shaving off the vertices, in a manner normal to the center, til the new surfaces meet is the same way you get to my original figures arrangement, starting with a cube. I have not taken angle measurements on my clay bar, for obvious reasons, but noticed just before, a rather familiar looking diamond in the middle of the pentagonal arrangement on the right, above. Was wondering if anybody knows the angles of the diamonds in my original figure. The measurement of the obtuse angle, and of the acute, and what the ratio of the length of one diagonal is, to the other. Regards, TAR

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Janus, But isn't the one on the right, our pentagonal arrangement, with the problems? I don't think you can use the one on the right, to seed a matrix with the "dual" characteristics of the one on the left. I know I had considered the one on the right. Probably could find a construction paper model like that (with flat faces) to prove it, if I had to, in some box or drawer. It just doesn't have the possibilities and is not quite so "loaded" with symmeties and nice finds, and "forced" qualities, as the one on the left, offers. My quess is, if pentagons were better than hexagons, we would not have honeycombs and snowflakes taking the hexagon route. All we have to back up the pentagon is starfish...well probably other things, but they do not come to mind. I was looking at some images on the web the other day, of crystals and electron microscope renderings and we have a lot of hexagonal stuff. I am trying to see what the geometric space rules are, that things tend to mind. To answer questions such as why electrons have the shell rules they have, for instance. Regards, TAR oh, and by the way, calling the figure "mine" is just a figure of speech, it is obviously "ours", and rather natural and evident and previously discovered, at that

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Janus, As I recall, the tetrahedra on the left do not complete the sphere. That is, if you make 12 regular ones and fit them together, they "look" like they are going to complete a "sphere", but they are a "little" off. Resulting in the reality, that if you are to join all the edges on the outside...you can't. The radii going toward the center are just a little too long...and you wind up with spaces. This would mean that twelve balls would not exactly fit around a center sphere of the same radius, in this arrangement. However, it appears that twelve balls do fit exactly around the figure on the right, and the edges shown are exactly one radii long. As are the internal edges of the six pyramids and eight tetrahedra, that point toward the center (not shown in the wire frame). This results in the fact that placing a ball at each vertices, each with a diameter equal to the length of an edge, and one in the center of the figure will result in the ping pong ball arrangement, and each ball will use exactly half its diameter to reach the outside edge of each of the twelve balls that surround it. Being that this positioning of balls is exactly the same as taking a regular cube and placing the appropriate size ball exactly at the midpoint of each of the twelve edges of the cube, and one of the same size in the exact center of the cube, the division of the cube into twelve equal solid angles, from its center point, is assured by this arrangement. As well, the division of the sphere in the center, into twelve equal solid angles is likewise insured. The diamond shapes in my original figure, are the result of forming the flat perpendiculars exactly half way between the adjacent pen holes(vertices). So in this regard, my close packing, wins, and space can be discribed, from any one point, as either 6 square areas and 8 triangular ones, in this arrangement, or the twelve identical diamond shapes that result from this arrangement. Regards, TAR

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Janus, I am working with an old laptop, without its original keyboard, that my daughter used in highschool. She is now a doctoral candidate at VT. I have put so many things on it and taken them off, the registry is probably a tangled mess. Anyway, I will try an older version of the Moray. Do you have to link the POV to the Moray, or the Moray to the POV. And thanks a lot for chrushing my hopes with the pentagonal pack. Looks like MD wins the close pack challenge. Still I think the intersecting planes in mine are sweet. As I recall, I had built the pentagonal one and discarded it, for some reason. The multiple axis in the one I settled on, looked more promising. But non-the-less, it looks like the triangle wins over the diamond...when it comes to a close packed sphere. You have any problems building out the one on the left? There was some reason I didn't like it. Something didn't work out. Can't remember what it was. Regards, TAR

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Thankyou Janus. That's the most beatiful thing I have ever seen. Its the figure I have been flirting with, but could never get a hold of. Thanks a million. (actually I have seen more beautiful things...but how the square planes and the hexagonal planes conspire at those angles to make each other, is really, really nice.) Symmetry to the max. Thanks a million. (by the way, my computer is way to underpowered for the POV and I couldn't get the modeling program to run, so your putting that together for me is PRICELESS.) You remain my superhero. Best Regards, TAR

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Janus, Wonderful. The fliped third hexagonal plane though is more valid here, because it renders the exact arrangement of the pen holes in my clay sphere. And the pen holes are exactly in the center of each of the diamonds. It's THAT arrangement I desire to see the "next" layer of. I have been unable to achieve it in actual balls, but you can do it in virtual ones. So this is very exciting for me, as I have had it on my mind for well over a decade. The retention of the intersecting hexagonal and square planes is crucial. MD65536, "(if you cut down the middle of an edge, you get your rhombus shapes, but if you cut from the corners you can make triangular shapes)" I cut them in half the way you said, and then again. The rhombus shape is retained to the same proportions, and I think its great. I noticed that the long axis of the diamond appears to be 1/4 of a sphere circumfrence long, and I am guessing/estimating that the short axis of the diamond is 1/6 of a sphere. These are nice figures, considering the 60 degree matrices and the 90 degree matrices that this particular arrangement of pen holes around a sphere, sets up. Also gives some credence to entertaining the TARadian as a useful measure of solid angles as that the figures cut are 1 tr, 1/16 tr and 1/64 tr, respectively, and they designate 1/12, 1/48, and 1/192 of a sphere respectively. In a rather solid and sure and regular way that is easy to visualize and compute. Regards, TAR

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Janus, That is fantastic. Except we need the top three flipped to get the intersecting hexagonal and square planes. That is, each ball on the first layer is in line with the center ball and a ball directly on the other side of the center ball. Where you see the two balls on the bottom three, you should see one ball on the top. In your build the top three were in the same holes as the bottom three. You have to rotate the whole third plane 60 degrees into the next set of homes. Then make the next layer. Regards, TAR You are still my hero. Can you PM me the rendering and modeling links? The priceless part I guess I will just have to borrow from you on occasion. (just for fun)

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Janus, That worked. Thanks. How much is that 3-D modeling program? How much is the Janus brain to operate it? I was wondering if you could do the ping pong ball figure. Another long term challange I have is to understand the shape you get when you build out the ping ball ball lattice, one "spherical" layer at a time. If twelve are on the first layer, how many on on the second? And the third? and so on. With this particular arrangement of "fitting" 90 and 60 degree angles, the intersecting hexagonal planes that establish square planes as well as you build out, I have a hard time visualizing what is going to happen. And have not determined what I should consider a complete "next layer". Seems its going to take a lot of ping pong balls and some correct decisions and insights...none of which I have obtained as of yet. Regards, TAR

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Janus, I received a "this video is private" attempting to view the build. But you're still my hero. That is fantastic that you can do that. Here are the 4 identical sections that MD noticed.

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Janus, That's great? How'd you do that? Is that actual or vitual? Regards, TAR Can we call that section a Janus if we find it does not yet have a name? Regards, TAR MD65336, Your'e right, we already have an SI unit for solid angle, that is nicely based on Pi so everything works out nicely already, nobody has the need for, or would care about a special unit. However, I still find it rather neat, and workable in visualizing how solid space fits together. It evovled, from an earlier "discovery" of mine drawing on clay spheres, and trying to work out the closest pack possible of same size balls. I know these things already have names, have been discovered and studied and measured and such, but it gives me a little sense of ownership to have found it out for myself. Here is my ping pong ball version of how space is put together. Twelve balls, fit exactly around a center ball, which results in some nice symmetries and intersection of hexagonal and square planes, when built out. Regards, TAR

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

imatfaal, OK, thanks, but I am having a little trouble understanding the % difference between the surface area subtended by the steradian and the surface area subtended by my TARadian unit. From Wiki: "Because the surface area A of a sphere is 4πr2, the definition implies that a sphere measures 4π (≈ 12.56637) steradians. By the same argument, the maximum solid angle that can be subtended at any point is 4π sr." If it takes around 12.56637 sr to subtend the sphere, and exactly 12 tr to subtend the sphere, then the tr is 1.0742 of an sr, or the sr is.9549 of a tr. I sort of like the tr better since they can be fitted together to cover the whole sphere exactly, whereas a circle on a sphere is hard to do anything with, visualizationwise. You can't readily see how many are going to fit around the sphere, or how to handle that funny shape inbetween you get when you touch 3 or 4 cones together. In any case the division you get, the shape you get when you carve the lines (radii) of a spherical rhombic dodecahedron to the center, can not be called a steradian, as it is neither conical in shape, nor circular at the subtend point, nor does it subtend a unit area of the surface of the sphere. It must have another name. Regards, TAR you could cut up a globe into those diamond shapes and lay them all out where you can see them at once you can't do that so easily with circles

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Thank you MD65536, That's it! Regards, TAR Do the wedges have a name? A pyramid with a rounded base? Or is there some name for the curvature being 1/12th of a sphere?

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

A few days ago I solved a challenge I had made myself, and think the division is neat, with a lot of nice symmetries and such, but several searches on the web and I have not found its name, or a breakdown of it, to study the angles and descriptions and such. So I am presenting it here, in the hopes that someone will recognize it, and point me to a link with its description. Its made of clay and was done by eye with pen and steak knife, so its not exact, but it works. What is this division called? Regards, TAR