-

Particle gravity cosmological evolution hypothesis

It should be a translation error. If you don't mind, you can rephrase your question, and I'll be happy to answer it patiently.

-

Particle gravity cosmological evolution hypothesis

Except for the initial conditions, anyone can try to derive it themselves, for it is inherently rational.

-

Particle gravity cosmological evolution hypothesis

It should be an expression error caused by translation. First of all, particles correspond to matter, which are the basic smallest units or a kind of setting; otherwise, the derivation cannot start. Secondly, the formation of the free layer is the effect of energy conservation and time statistics in the gravitational field. The simplest way to understand it is: if they converge into a mass, where do the initial kinetic energy and potential energy go? Therefore, there is energy driving some particles to move in the aggregate. Names are just for classification and do not change the particles themselves. Fixation is a statistical result. Due to the gravitational force of the core, particles are bound to move in a parabolic trajectory. Under the gravitational effect of the core, when particles reach the farthest end, their speed is almost zero, so they stay at the farthest end for half the time and repeat this process for the other half. Therefore, the particles that make up the free layer are changing all the time. At present, it is somewhat difficult for me to subdivide the structure of the free layer. 25 Core Mechanism: Randomly Detaching Particles = Thermal Radiation 1. Structural Characteristics of Saturated Particle Clusters (Chapters 3-4) • After the formation of an atom, its original "static core" is replaced by a group of low-kinetic-energy particles (not absolutely static). • These particles are located in the central region of the atom, with an extremely high collision probability (due to high density and low kinetic energy), but energy exchange is confined to local areas. 2. The Nature of Radiation • Internal collisions generate directionless detaching particles: ◦ During the collision of low-kinetic-energy particles, energy is randomly transferred to individual particles, enabling them to gain escape kinetic energy (Chapter 4). ◦ These particles have no collective direction and their movement trajectories are random (Chapter 5). ◦ Result: ◦ Detaching particles carry energy and dissipate into the environment → forming heat (a statistical effect of low-speed detaching particles). • Cannot form photons (require directed particle streams).

-

Particle gravity cosmological evolution hypothesis

I'm sorry, it might have been an error in my operation. I translated and sent it using the translation interface. During my simulation of N-body motion, I observed that the initial structures undergo re-evolution under gravitational effects, showing striking consistency with some experimental results. This has led me to attempt deducing the existing physical framework from a single condition and reshaping the theoretical system. “sonoluminescence” “sonoluminescence”

-

Particle gravity cosmological evolution hypothesis

If it's just for the sake of understanding, I recommend that you look into the Oort cloud in the solar system structure, which is similar to the particle clusters in the initial microscopic evolution process. I get what you mean. The way this text is written does come across as a bit unpolished, but honestly, it’s more like a lengthy idea or speculation. The thing is, when I only present parts of it, no one seems to grasp my train of thought. This piece isn’t meant to be some kind of academic report. What I ultimately hope for is that someone might try to approach things from this angle. The fundamental nature of light is a question well worth pondering. A single atom emits light only under external conditions, but what is the root of these external conditions? Most of them come from chemical reactions. The atomic collisions I mentioned, along with an experiment where a water bubble emits light, can both serve as evidence. As for predictability, I have also put forward more macroscopic differences. The molecular structure of C₂H₂ remains merely a theoretical speculation to this day. I have tried to verify it through longer carbon chains, but the reality is that there will always be new theories to explain new phenomena.

-

Particle gravity cosmological evolution hypothesis

In the model, microscopic particles form high-density clusters (such as "saturated free layers") through long-range gravity. When the particle density reaches a critical value (e.g., at the atomic scale), the cumulative effect of gravity can exceed traditional calculations — this is similar to the formation mechanism of dark matter halos but occurs at a smaller scale. Derivation of "apparent forces": • The strong interaction (nuclear force) is essentially the compressive strength of the saturated free layer (requiring the pushing apart of high-density particle groups). • The electromagnetic force is the directional restoring force caused by the imbalance in the loss of particles in the adsorption layer. Both are macroscopic manifestations of gravity under specific structures. That's fascinating! During my simulation of N-body motion, I observed that the initial structures undergo re-evolution under gravitational effects, showing striking consistency with some experimental results. This has led me to attempt deducing the existing physical framework from a single condition and reshaping the theoretical system.

-

Particle gravity cosmological evolution hypothesis

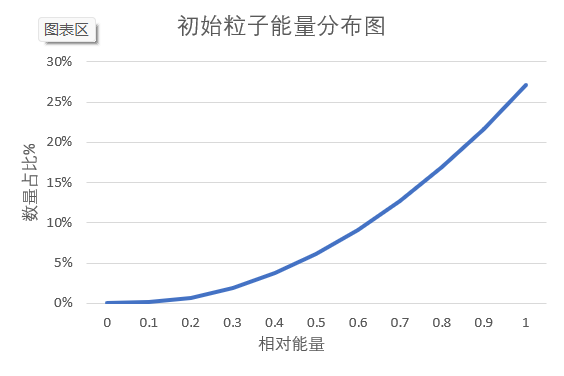

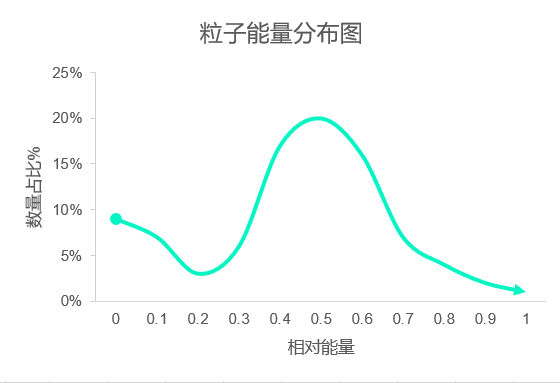

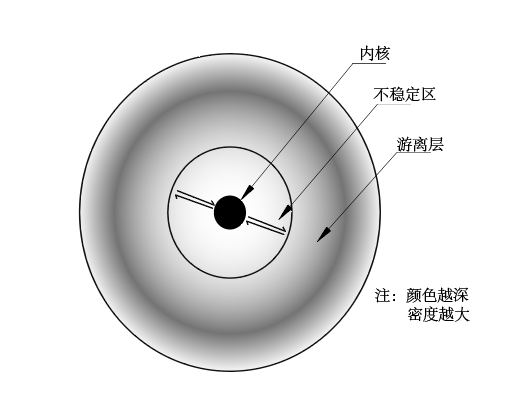

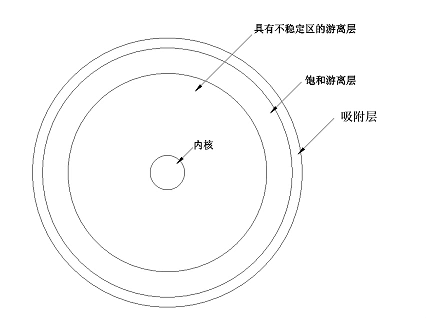

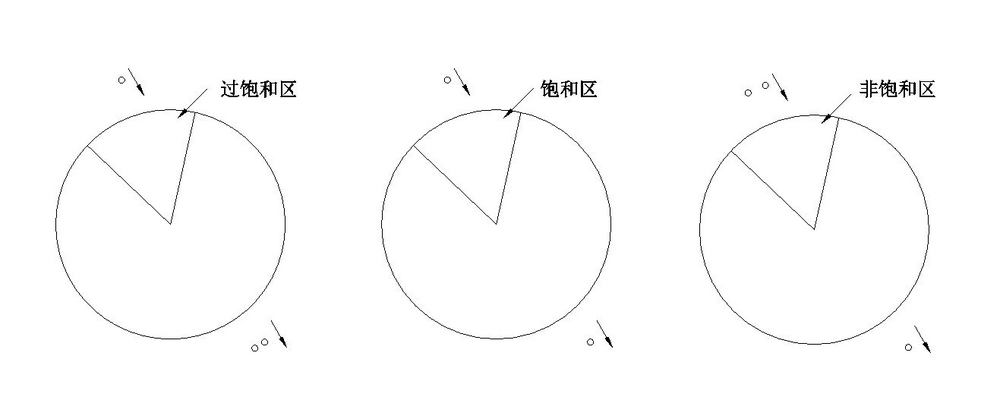

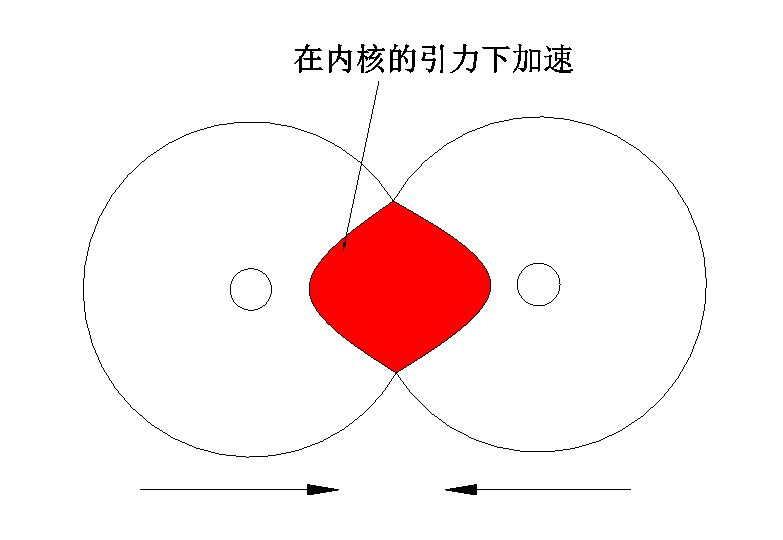

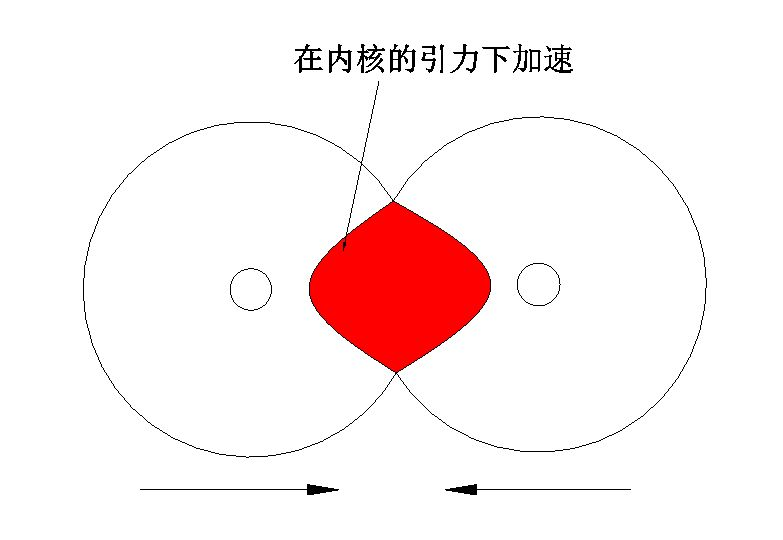

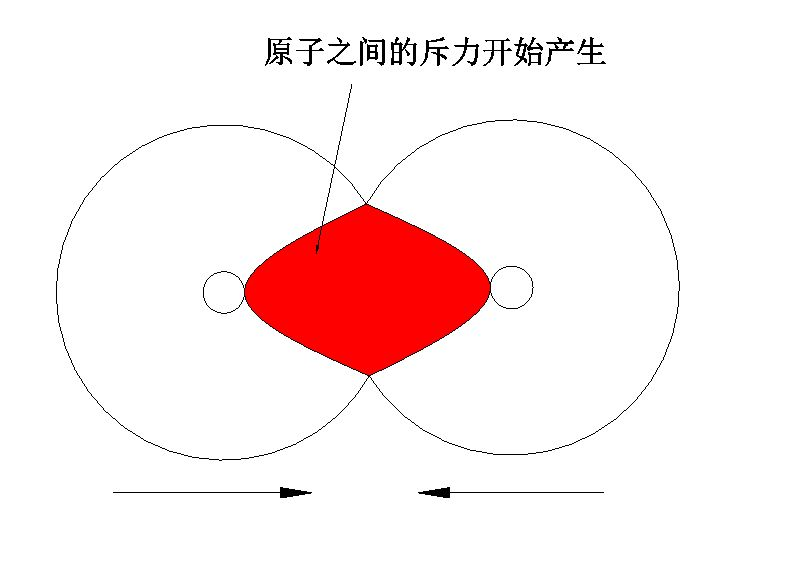

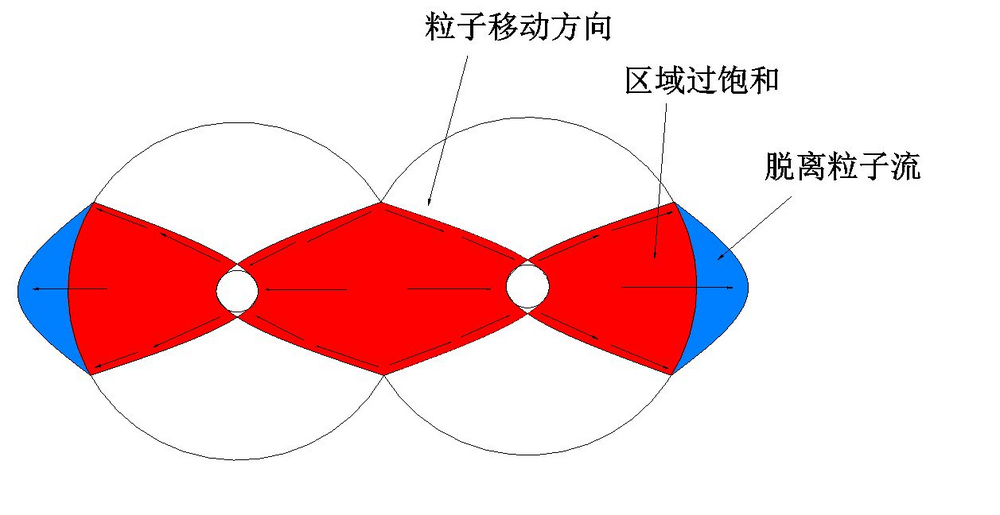

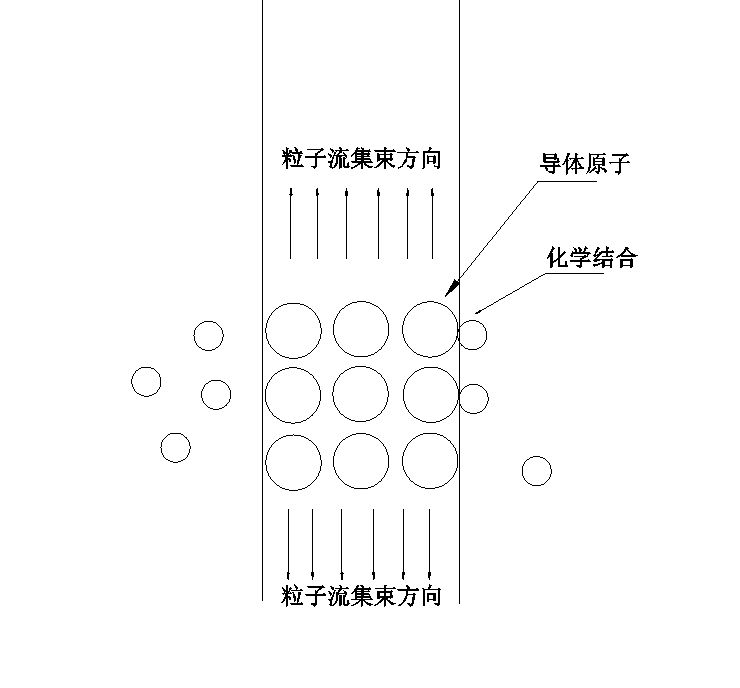

This article is translated by machine. Cosmic Origin - Conjecture of the Dust Theory AbstractThis paper proposes a particle-cluster dynamics cosmological model based on universal gravitation ("Dust Theory"), reconstructing the material evolution framework from randomly distributed irregular fundamental particles through gravitational interactions. The model reveals that particles self-organize into a three-tiered structure: the core (a low-kinetic-energy stationary center), the free layer (a dynamic particle zone dominated by potential energy), and the escaping particles (high-energy escaping particles). Particle clusters evolve hierarchically through collisions: initially unsaturated structures absorb escaping particles from the environment to expand their free layers; multiple particle clusters converge to form a "thermal environment" (where temperature is defined as a function of the kinetic energy and density of escaping particles); and when the free layer reaches saturation, the structure evolves into an "atomic" configuration—its core periodically radiates escaping particles, while its outer adsorption layer continuously exchanges with environmental escaping particles.Building on this, the theory provides a unified explanation for key physical phenomena: 1.The nature of light: When atoms collide, interactions between their free layers generate impact particles, which are directionally transmitted via core energy to form a beam-like stream of escaping particles ("a photon"). This framework reconstructs double-slit interference: particle streams, after passing through slits, exhibit density-distribution superposition to form interference fringes. 2.Thermodynamic mechanism: Heat is defined as the dynamic equilibrium between an atom’s adsorption layer and environmental escaping particles. Frictional heat arises from the stripping of free-layer particles, creating unsaturated zones. 3.Electromagnetic origin: Static electricity results from disruptions in the free-layer particle cycle (e.g., wool friction temporarily stores particles before they are absorbed by adjacent atoms). Magnetic force is attributed to stable free layers constructing directional energy channels, enabling low-loss particle flow conduction. 4.Fundamental forces: The strong interaction corresponds to the high-density resistance of saturated free layers (with an interaction range ≈ atomic radius), while the weak interaction stems from directional restoring forces caused by imbalances in adsorption-layer particle loss when atoms approach.This model connects microscopic particle behavior with macroscopic phenomena using universal gravitation as the sole foundation, challenging traditional multi-force frameworks (e.g., explaining acetylene linearity requires introducing the ad hoc "conjugate shortening" exception). It offers a parsimonious explanation for cosmic structure formation, force unification, and thermodynamic-light-electric-magnetic phenomena, though further experimental validation is required. Keywords: particle cluster, dynamic model, universal gravitation, formation of light 1 Basic ConditionsThe appeal of this theory lies in that it deduces all theories in a forward direction, rather than being an afterthought. What kind of conditions can be considered the simplest? I think the most fundamental is matter, which is the starting point of everything. But matter alone is not enough; there must also be forces. Which force is the most likely candidate? The four fundamental forces? No, I think only one force can be used for an attempt, and that is undoubtedly universal gravitation. The universality and directness of universal gravitation are key to its selection, and it also obeys Newton's laws. Although the role of universal gravitation in the microcosm is defined as extremely weak, this theory does not deny this fact. However, this does not mean that other forces need to be introduced to achieve the desired results. The core of this paper, however, is not to explore the nature of universal gravitation, but merely to cite its effects. According to the law of universal gravitation, we know that there is an attractive force between any two objects with mass. This serves as an excellent original foundation for us. Next, we should analyze in detail what kind of matter the basic matter is—for example, is it a sphere or a polyhedron? Is its surface completely smooth? However, I believe the most important thing is not the form of the basic matter, but the relationship between different matters. Here, the most ideal scenario would involve particles with uniform shape and mass. But the more ideal the particles, the lower their possibility of existence. Therefore, the most likely candidates are irregular polygonal particles with slightly different masses, which, as the most basic particles, are naturally indivisible. In any case, the most significant outcome dictated by these conditions is compliance with the law of conservation of energy. When two or more particles collide, energy transfer and particle rotation occur. Thus, the specific form of particles is not important; what we need to understand is the consistent results arising from their interactions. Finally, we need to discuss the initial distribution of these substances in space. There are only two possibilities: either they are randomly distributed in space, or they form a single cluster. However, if particles have already aggregated into clusters, the research value of the model based solely on universal gravitation would be limited. Therefore, we can only assume that they are randomly distributed in space, ensuring a certain degree of dispersion without being overly dense. It should also be emphasized here that no initial velocity is imparted to them. 3 Formation of Particle ClustersIn the initial stage, under the action of universal gravitation, substances attract each other, converting the potential energy between them into kinetic energy, and thus velocity comes into being. This is a large-scale contraction on the macroscopic level. According to the formula of universal gravitation, we know that the gravitational force between particles is related to distance and mass. Since our particles are randomly distributed and the space is relatively infinite, even in the process of large-scale contraction, there will be some regions where the combined mass of particles is greater than that of other regions. As a result, these high-mass regions will temporarily become centers, attracting particles from other regions to converge. The reason why they are called "temporarily" regional centers is that these high-mass particle regions will also converge over time. However, due to the factor of distance, this process will take a longer time. For example, there are many galaxies in space, and each galaxy contains many stellar systems. Therefore, in the entire initial system, all particles have their initial direction of movement towards a destination, which creates particle boundaries and divides the entire universe into countless regions. Next, we will conduct an in-depth analysis of the continuous evolution process of some regions, which I collectively refer to as particle clusters. Initially, it is just a chaotic collection of particles with no obvious structure, but this is only the beginning. Under the continuous action of universal gravitation, the particle cluster will keep converging. The farther a particle is from the center of the particle cluster, the greater the potential energy it has. Let the initial maximum potential energy be 1, as shown in Figure 1. Figure 1 Initial Particle Energy Distribution Due to the inertial thinking of most people, they will mistakenly think that all particles will converge into a single mass and gather at one point. In fact, this is not the case. Because of the law of conservation of energy, there must be substances that carry the potential energy between other particles in the form of kinetic energy, and this process is what we need to demonstrate. In the process of continuous convergence of particles, most particles will move back and forth around high-mass regions. In this process, the distance between some particles will suddenly decrease, leading to an increase in the gravitational force between them, which affects their mutual movement trajectories until the particles collide. This is the initial effect of universal gravitation, causing collisions between particles that were originally unrelated. This process leads to energy transfer between particles or the spin of particles, but here we can simply ignore the energy changes caused by particle spin. According to the law of conservation of energy, the collision of substances will affect the state of both. Therefore, particles can be simply divided into three types. The first type is low-kinetic-energy particles that lose most of their energy due to collisions or are located in the center of the particle cluster, which eventually form a relatively static mass center core. The second type is free particles in the high-density particle region outside the center of the particle cluster. Due to the high probability of collisions, after continuous collisions, the energy is evenly distributed, and they move around the core of the mass center. The third type is particles that have relatively high energy without energy equalization (through collision) after collision, which are enough to break away from the gravitational pull of the particle cluster and become particles wandering in the empty space. These particles will take away the energy of other particles in the initial particle cluster. Later, I will briefly analyze the generation process and role of these three types of particles in the particle cluster, which will be specifically explained in the discussion of the generation of phenomena. During the movement of particles, most collisions are non-central, which results in two types of particles with higher and lower kinetic energy, and also makes the particles spin. In this process, particles that keep losing energy will be continuously generated. As the kinetic energy of these particles decreases, they will get closer to the mass center of the particle cluster, converting potential energy back into kinetic energy until the potential energy is completely transferred. In this process, the particles at the mass center of the particle cluster will continuously expel energy-carrying particles into the free region, which makes the distance between some particles keep shrinking until they are close to each other, thus forming a relatively static core. In the particle cluster, this core not only serves as the mass center but also acts like the stator in a Newton's cradle. Because this process exists all the time, the radius of the core will continue to increase over time (with movement), but there is also a limit. Because of the law of conservation of energy, and in this system, energy can only be carried by particles. Therefore, if there are relatively static particles, there must be particles with corresponding mass to carry their energy. The total energy in the particle cluster remains unchanged, but collisions cause changes in the overall energy structure, as shown in Figure 2. Most particles that carry or inherently have energy will move within the gravitational range of the core, with the core as the center, thus forming free particles. Regarding free particles, many people have a misunderstanding that free particles move in a circular motion around the core, which is wrong. Besides circular motion, most free particles will collide with the core under the gravitational pull of the core. However, when colliding with the core, the energy will not disappear. As mentioned earlier, the core is equivalent to the stator in the center of a Newton's cradle. After free particles collide with the core, a number of particles carrying equal energy will be generated at the other end of the core. Due to the movement away from the core, similar to parabolic motion, the gravitational force changes during the movement, and the kinetic energy at the farthest end is almost zero. This makes the free particles at the farthest end stay there for most of the total time, so most free particles are approximately stationary and accumulate in large numbers at the farthest end of potential energy. However, over time, they will still fall towards the core and start a new parabolic motion, so that the radius of the core maintains a dynamic balance in this process. In the derivation process, we find that the movement of free particles is complex and changeable, but it is also found that most free particles move in a parabolic manner, and their energy is converted into potential energy in the particle cluster. However, free particles will also collide during movement, which is related to the particle density in the free region. The higher kinetic energy particles generated by collisions are still within the gravitational range of the core, so there will be a corresponding farthest position, called the free layer, which is essentially related to the mass of the core. Some free layers will be saturated, that is, the number of particles that can exist at a fixed distance will balance within a certain range, which is related to the kinetic energy and density of particles. The particle density in each region will have a regional value fluctuation. In regions with high particle kinetic energy, a small number of particles can reach saturation, and the corresponding particle density is smaller. The closer to the periphery, the greater the particle density will be. However, due to the insufficient initial number of particles, after reaching the maximum value in a certain region, it gradually decreases. We need to consider not only the factor of the core's gravity but also the gravity of the entire particle cluster. As shown in Figure 3, it is the structure of the particle cluster under a stable structure. Figure 3 Particle Cluster Structure In regions with high particle density, energy equalization will occur because the probability of collision in these regions is higher in some cases. For example, when absorbing a high-energy particle, during the collision or under the traction of universal gravitation, the energy will be evenly distributed to more other particles, resulting in the particle itself being assimilated and its speed tending to be consistent. Therefore, some regions of the free layer are more likely to be saturated. After the free layer is saturated, it will expand outward, which is related to the mass of the core. Of course, it is still far from the saturation of the maximum free layer from the core. That is, if there is a large number of particles to supplement, the radius of the particle cluster will be larger than that of the initial particle cluster until another dynamic balance is achieved. To understand it in another way, this is only the first stage of particle convergence. With continuous concentration, the overall gravitational effect intensity increases, enabling it to absorb a number of particles far more than the initial number of particles. Without additional particle supplementation, an unsaturated particle cluster is formed. In summary, free particles are the particles that carry most of the energy of the particle cluster, and most of the energy is stored as potential energy, with part of the energy being the overall kinetic energy of the particle cluster. Escaping particles are some particles that carry too much energy, lose little energy during the movement of escaping from the system, have no collision or collide with particles with low kinetic energy, and then exceed the gravitational range of the particle cluster and escape from the particle cluster system. Most of them are generated in unstable regions of the particle cluster where the collision probability is high. For almost stable particle clusters, they hardly generate escaping particles. Although escaping particles will carry part of the energy of the particle cluster, the entire system will also absorb escaping particles generated by other particle clusters, forming a complement, so that the overall energy does not change much. And this initial particle cluster structure is similar to the currently defined dark matter. In this conjecture, the particle cluster is only a product of a stage and a basic unit for the next evolution. As mentioned earlier, the particle cluster at this time is only an unsaturated structure, which can absorb a large number of detached particles and expand its own free layer. To my knowledge, this characteristic is the same as that of virtual particles. 4 Formation of Thermal Environment and Its InfluenceIn the process of large-scale convergence, particle clusters also gradually gather, i.e., on a larger scale. During this process, countless particle clusters converge from afar to form a new large-scale region, and the particle clusters also acquire a certain amount of kinetic energy, which seems somewhat similar to the formation of the initial particle clusters. The free layers of the initial particle clusters are not saturated, and there is little interaction between them. Therefore, the initial stage can indeed be simply understood as collision and combination. However, this is different from the collision of particles. First, we need to briefly analyze what happens during the combination process of particle clusters. When two original particle clusters combine, each stable structure, including the core structure, will be disrupted. The core is no longer relatively stationary, but since it originally existed in a relatively stationary state and is very dense, a part of it still becomes the core of the new particle cluster. At the same time, a large number of particles will absorb the kinetic energy of the particle clusters before combination, so most of them will re-enter the free layer, and a large number of escaping particles will also be generated. In simple terms, after combination, the situation where the core mass of 1+1 < 2 and the free particle mass of 1+1 > 2 will occur, with some being lost in the form of escaping particles, and unstable regions appearing between the core and its surroundings. So, what is the point of saying all this? The key lies in the escaping particles. When particle clusters converge with each other, it is not just one or two pairs combining, but countless pairs of particle clusters within a certain space combining with each other. This will result in a large number of flowing escaping particles between numerous particle clusters, which represents the formation of an environment, and I call this environment "heat". What is the function of such an environment? During their movement, escaping particles will collide with other particle clusters. In most cases, part of the energy of the escaping particles will be transferred to other particles and absorbed by the particle clusters. However, as we explained earlier, each region of a particle cluster can only have a certain particle density, and the excess particles can only cause the free layer of the particle cluster to expand outward. Such expansion makes the particle cluster continuously grow, forming a positive feedback. Nevertheless, this expansion is also limited. Because when a particle cluster absorbs any escaping particle, the potential energy contained in the particle alone already exceeds that of the particle with the maximum energy in the cluster. After absorbing a large number of particles, the particle cluster system will continuously increase the average particle energy, thereby changing the structure of the overall free layer. The details will not be elaborated here. The continuous combination of particle clusters generates escaping particles that continuously replenish this environment, and in this environment, they continuously supplement other unsaturated particle clusters. In this environment, the number of free particles that the core can carry will gradually reach the maximum, thus forming a saturated particle cluster, called an atom, as shown in Figure 4 for simplicity. Figure 4: Simplified Diagram of the Simplest Atom At this point, the core is composed of partial small cores from multiple particle clusters. Meanwhile, the number of unstable regions inside the atom increases, and the unit density of the outermost saturated free layer reaches the maximum. Its overall mass can absorb some escaping particles with a certain amount of kinetic energy. Due to the distance factor, the gravitational effect of the saturated free layer is greater than that of the core, generating outermost free particles, i.e., the free layer of the particle cluster, which I call the adsorption layer. This is also the area with the most interactions with escaping particles. Of course, the actual situation is definitely more complex than this structure, which will not be elaborated on here. However, it should be noted that the core is an unstable region. During the stabilization process, it occasionally emits escaping particles, which is thermal radiation. Following this, three states of the free layer are introduced: supersaturated, saturated, and unsaturated. For an atom with a fixed mass, there is a mathematical boundary between the free particles in the saturated free layer and the escaping particles. In the process of normal movement, such as friction, adding some energy will excite some free particles to become escaping particles, which gain a large amount of heat in a short time but are eventually replenished by the environment. For a saturated and stable atom, when it absorbs a certain amount of escaping particles, an unstable region will first form for temporary storage. Then, the particles transfer energy to other particles through universal gravitation or collisions. For the saturated atom, this energy will generate a number of escaping particles with equal total energy components, forming a stable dynamic change. Under normal circumstances, the kinetic energy of the escaping particles absorbed in space will be transferred to multiple other particles, eventually making most escaping particles fall into the same speed range. When a supersaturated free layer absorbs particles, it will generate more escaping particles than the number of absorbed ones. When an unsaturated free layer absorbs particles, it will generate fewer escaping particles than the number of absorbed ones, as shown in Figure 5. Figure 5: Simplified State Diagram of the Free Layer The essential difference between these free layers lies in the change in the relationship between kinetic energy and particle density, and ultimately, all free layers tend to be saturated. The environment will continuously maintain a certain number of escaping particles, which fill the region where atoms gather, forming a thermal environment. Under normal circumstances, the movement trajectory of low-speed escaping particles is affected by the gravity of atoms. Most of them only flow back and forth in the space between atoms, attaching to atoms but not belonging to any particular atom, just like flowing water. They affect the movement of atoms. This theory can more simply explain the principle of air conditioning: atoms are like sponges, and heat is like water in the sponges, transferring heat during compression and release. In the process of frictional heating, it is the outermost free layers of atoms that collide during movement, carrying away some free layer particles, forming a partially unsaturated free layer. These particles become escaping particles, generating a large amount of heat. However, since there is no change to the atomic core, the unsaturated free layer is restored under the compensation of the thermal environment. This theory also unifies all heat-related phenomena under the same model, and the relevant experimental evidence has long been applied in our lives, such as the flowing gas cooling method. Because the modern definition of heat is the movement of molecules and atoms, while this theory defines heat as the escaping particles outside atoms, it only requires fixing molecules or atoms within a certain range. In existing theories, heat would not change much, and with flowing gas at normal temperature, heat would still not change significantly. Of course, existing theories have been self-consistent after adding various supplementary theories, but this theory is different. The flowing gas moves at a high speed relative to the fixed atoms; after collision, the outermost free particles of the fixed atoms are converted into escaping particles, forming an unsaturated region. The generated escaping particles are then carried away by the high-speed flowing gas, and this unsaturated region takes away the deeper heat in the atomic region, thereby achieving cooling. This method is applied in the cooling of various electronic devices. 5 Generation of LightWhat is light? The divergence in people’s understanding of light mainly centers on the double-slit experiment. However, this paper will revisit the nature of light from the perspective of particle theory. First and foremost, the most fundamental property of light is its ability to carry information. Since we perceive the world through light, it must be generated in a regular manner—random, meaningless motion would serve no purpose. Thus, the critical question is: how is light produced? Without external intervention, a single atom (the saturated particle cluster mentioned earlier), even with numerous internal unstable regions, will only randomly generate a few high-speed escaping particles through internal collisions, which can propagate in space. However, such random generation is meaningless and cannot be the light we perceive, as confirmed by modern experiments. Therefore, a single atom cannot produce light without external interference. So, how should light be generated? A careful consideration reveals that light originates from the collision and combination of two atoms. Under certain conditions, when two particle clusters combine, their outermost free layers—where particle density is highest—make first contact. This means numerous particles gain initial velocity toward the core upon collision. Notably, these colliding and absorbed particles do not affect the overall motion before striking the core, as shown in Figure 6. Figure 6: Combination of Particle Clusters Particles in the collision zone not only acquire initial velocity from the collision but also accelerate under the core’s gravitational pull; these are called "impact particles." The particle clusters themselves continue moving at their original speed, creating a time lag with the generated impact particles—providing a window for reaction. As the cores move closer, they continuously supply such impact particles. It is important to note that the velocity direction of these collision-generated particles, under the core’s gravity, is almost directly toward the core. They do not possess velocity or orbits to circle the core but instead all rush toward it. Initially, this creates a repulsive-like force, similar to a gust of wind resisting forward movement. As impact particles accumulate, the repulsive force becomes strong enough to keep the two atomic cores at a certain distance, as shown in Figure 7. Figure 7: Process Diagram of Impact Particles However, when the generated impact particles collide with the core, the core still acts like the stator in a Newton’s cradle: through the core as an intermediary, new particles are propelled outward from the opposite side. Some particles reconvert their kinetic energy into potential energy. These impact particles collide with the free layer and are partially absorbed, forming a supersaturated region. This supersaturated region acts like a Newton’s cradle, reducing kinetic energy loss for subsequent impact particles. Under the influence of this supersaturated region, most impact particles become escaping particle streams with little loss of kinetic energy, as shown in Figure 8. Figure 8: Generation of Escaping Particle Streams These streams then propagate through space in this form. In essence, the kinetic energy of the escaping particle streams originates from the initial kinetic energy of the atoms. However, as the impact particles move outward, they undergo continuous collisions in various regions, equalizing their energy. The kinetic energy carried by each particle does not differ significantly. The number of particles corresponds to the portion of free layer particles lost during the combination process; another portion maintains the repulsive force between atoms, and a supersaturated region forms at the tail of the atoms. The complex post combination changes of the two particle clusters will not be elaborated on here. What characterizes these collision-generated escaping particle streams? The central region contains a concentrated particle stream propagating outward at a certain velocity. Such a particle stream fulfills the basic conditions described earlier and represents the meaningful componentthis beam of escaping particles is defined as a "photon." It is important to clarify that a photon does not refer to a single constituent particle; rather, it represents the smallest unit of light generation. Thus, one photon denotes the smallest unit of light produced by an atom: a beam of escaping particle streams composed of numerous particles. Additionally, the generation process of this particle beam generally results in a probability distribution with higher density in the center and lower density at the edges. During propagation, the density per unit area changes, causing the particle stream to expand to a certain range within a short time. 6 Applications of the Theory(1) Under these conditions, we re-explain the double-slit interference experiment. When a beam of light (i.e., an escaping particle stream) encounters double slits, part of the particle stream passes through the two slits. Due to the particle stream’s density distribution, the central region with higher density is more likely to pass through the slits. The particle streams passing through the slits continue to diverge outward, but their divergence pattern is altered by the slits, forming specific divergence angles and directions. When these particle streams meet at the screen, their density distributions overlap. Depending on the particle density and the angle of encounter, particle density increases in some regions and decreases in others, forming interference fringes. These interference fringes are essentially the statistical result of particles deposited on the screen by escaping particle streams of varying densities. In regions with high particle density, more particles arrive and accumulate, forming bright fringes; in regions with low particle density, fewer particles arrive, forming dark fringes. Even when a single photon is emitted (i.e., one photon), since a photon is essentially composed of a large number of particles, the particles in each emitted photon still follow the same interference rules. Over time, the distribution of these particles on the screen gradually accumulates into an interference pattern. (2) The relationship between light and heat: When an escaping particle stream (light) is absorbed by an atom, even if the atom is saturated, part of the light is still needed to push the atom into a supersaturated state. This allows the trajectory of subsequent escaping particle streams to scatter part of the light, which also refracts under the atom’s gravitational pull. The supersaturated region within the atom does not persist indefinitely; due to exchanges with the external environment, part of the light is continuously converted into heat—i.e., high-speed escaping particles become low-speed escaping particles (heat) after energy transfer. (3) The process of light generation can be associated with electrochemistry. In this theory, electrons are analogous to the free layer of particle clusters. Electrochemistry essentially involves the combination of substances, generating a large number of escaping particles. This theory can inherently explain a common issue in electrochemistry: battery spontaneous combustion. Because the combination occurs at the electrodes, which also act as conductors, as shown in Figure 9. Figure 9: Electrochemical Process Due to the law of conservation of energy, the directional flow of concentrated particle streams consumes the potential energy between the conductor’s atoms, causing irreversible changes in the conductor’s atomic structure. Some regions of the conductor lose their ability to conduct the stream. This prevents complete transfer of subsequent concentrated particle streams, which accumulate in large quantities in the electrolyte, causing a rapid temperature rise and spontaneous combustion. To avoid this, the shape or structure of the conductor needs to be modified. 8 MagnetismI originally intended to reserve this part of knowledge about magnetism to protect the theory I have developed. However, breaking through inherent cognition always seems difficult. Therefore, I have decided to no longer hold back the elaboration on magnetism, so as to provide a complete preliminary framework for the entire theory. What is magnetism? Traditionally, a magnetic field is often defined as a special kind of substance, mainly to facilitate understanding. I respect different ways of cognition, and the following deduction only provides a new way of thinking. Given that the definition of magnetism is extensive and the theory is not yet mature, we will start with a simple magnet for analysis. Based on the atomic particle model, each atom has a free particle layer. This structure stores a large amount of potential energy of particles, especially the outermost free particles. The larger the atomic core, the greater the mass of its free layer is usually. Then, under such a structure, how is magnetism generated? First, a common misunderstanding needs to be avoided: is magnetic force a new substance independent of matter? The answer is no. Magnetic force must abide by Newton's laws and the basic substance, the only particle, as we initially stipulated. Then, where does it originate? We know that friction can generate static electricity. In the world of microscopic particles, what is friction? It is the collision between the surfaces of two atoms. Another misunderstanding is easy to arise here: the particle model we deduced can be roughly regarded as an aggregate of particles. Since it is a collision between two particle aggregates, should the particles be scattered? This is not accurate. The key point is that the force you apply cannot be completely and directly transferred to the atoms involved in friction. The force is mainly transmitted and pulled through the attractive force between atoms (not universal gravitation), and the efficiency of this transmission is limited. Imagine hitting sand with a piece of paper, which is completely different from hitting it directly with your hand. The paper can only knock off a small part of the sand, and at the same time, the paper itself will bend and deform. The collision principle of the free layer on the atomic surface is similar to this. Friction mainly causes the free layer in the contact area to be in an unsaturated state. Then, what is the relationship between this unsaturated state of the free layer and magnetism? We need to place our thinking within the overall framework of universal gravitation. The mere lack of mass (an unsaturated region means a reduction in free particles there, i.e., a local decrease in mass) seems to have no direct connection with magnetic force, and even cannot be justified. This is because we always fix our thinking on a phenomenon to the substance itself, for this is not something that will happen when the state of the substance changes. In the previous discussion, we clarified a key characteristic of the unsaturated region: it can receive a large number of external particles and only emit a small number of particles. Under the action of the thermal environment, the unsaturated region will gradually return to a saturated state, but this takes time and is not completed in an instant. During friction, the situation is different for atomic structures (such as wool) that have an adsorption layer and can temporarily store low-speed escaping particles. The composite structure of wool enables it to temporarily capture these escaped particles during the friction process. 8 Magnetism I originally intended to reserve this part of knowledge about magnetism to protect the theory I have developed. However, breaking through inherent cognition always seems difficult. Therefore, I have decided to no longer hold back the elaboration on magnetism, so as to provide a complete preliminary framework for the entire theory. What is magnetism? Traditionally, a magnetic field is often defined as a special kind of substance, mainly to facilitate understanding. I respect different ways of cognition, and the following deduction only provides a new way of thinking. Given that the definition of magnetism is extensive and the theory is not yet mature, we will start with a simple magnet for analysis. Based on the atomic particle model, each atom has a free particle layer. This structure stores a large amount of potential energy of particles, especially the outermost free particles. The larger the atomic core, the greater the mass of its free layer is usually. Then, under such a structure, how is magnetism generated? First, a common misunderstanding needs to be avoided: is magnetic force a new substance independent of matter? The answer is no. Magnetic force must abide by Newton's laws and the basic substance, the only particle, as we initially stipulated. Then, where does it originate? We know that friction can generate static electricity. In the world of microscopic particles, what is friction? It is the collision between the surfaces of two atoms. Another misunderstanding is easy to arise here: the particle model we deduced can be roughly regarded as an aggregate of particles. Since it is a collision between two particle aggregates, should the particles be scattered? This is not accurate. The key point is that the force you apply cannot be completely and directly transferred to the atoms involved in friction. The force is mainly transmitted and pulled through the attractive force between atoms (not universal gravitation), and the efficiency of this transmission is limited. Imagine hitting sand with a piece of paper, which is completely different from hitting it directly with your hand. The paper can only knock off a small part of the sand, and at the same time, the paper itself will bend and deform. The collision principle of the free layer on the atomic surface is similar to this. Friction mainly causes the free layer in the contact area to be in an unsaturated state. Then, what is the relationship between this unsaturated state of the free layer and magnetism? We need to place our thinking within the overall framework of universal gravitation. The mere lack of mass (an unsaturated region means a reduction in free particles there, i.e., a local decrease in mass) seems to have no direct connection with magnetic force, and even cannot be justified. This is because we always fix our thinking on a phenomenon to the substance itself, for this is not something that will happen when the state of the substance changes. In the previous discussion, we clarified a key characteristic of the unsaturated region: it can receive a large number of external particles and only emit a small number of particles. Under the action of the thermal environment, the unsaturated region will gradually return to a saturated state, but this takes time and is not completed in an instant. During friction, the situation is different for atomic structures (such as wool) that have an adsorption layer and can temporarily store low-speed escaping particles. The composite structure of wool enables it to temporarily capture these escaped particles during the friction process. 9 Changes to the Underlying Logic of PhysicsWhy does your theory suggest that atoms are filled with particles, whereas Rutherford's alpha particle scattering experiment leads us to believe that atoms are mostly empty? This is clearly a preconceived idea. First, the particles used by Thomson were large-mass, high-energy particles produced by atomic decay, while the free layers consist of countless small-mass particles. Therefore, the探测 (detecting) particles can easily penetrate most regions of the atom and only deflect when approaching the internal high-energy regions. In macroscopic statistics, this manifests as almost unimpeded penetration. It is like using a stone to explore the shape of a piece of elastic cotton. Although the cotton exists in space, we can learn about its internal conditions through the stone. When we observe with light, which is also composed of small-mass 探测 (detecting) particles, we will observe more invisible regions. The adsorption layer, which is essentially the same as photons, will only be easily penetrated under complex interactions and cannot be directly observed. However, the adsorption layer outside the atomic radius can be observed through physical interactions, namely weak interaction forces. The specific mechanism is as follows: when two atoms approach each other, the adsorption layers outside the atoms collide first, generating a weak repulsive force. During the process of moving away, if the direction of movement is opposite to the direction of particle absorption, the adsorption layer will then exhibit a weak attractive force that exceeds gravity. Its essence is a directional restoring force generated by the imbalance of the adsorption layer particle flow due to absorption or loss, and the range of this force is consistent with the atomic scale. The strong interaction force is even easier to explain. The saturated free layer is a high-density, high-mass atomic structure. Any particle entering this range needs to overcome huge resistance to push aside the high-density saturated free particle group. Moreover, the range of strong interaction forces is 10^(-15)m to 10^(-10)m, while the atomic radius is 10^(-10)m, which precisely confirms this view. Finally, in terms of chemical structures, the biggest challenge is intuitively different from modern theories. In this theory, after two atoms combine, a supersaturated region will form in the symmetric direction of the bonding area, which will prevent other atoms from combining in this region. In other words, there will be no other atoms on the short axis of the atomic bond. This is a definite conclusion in this theory. This explanation works for most molecular structures without any anomalies, but it directly challenges the atomic collinearity of acetylene. However, the deduced theory is consistent with the special cases in hybrid orbital theory, such as the phenomenon of conjugated shortening in butadiyne. The essence of this conclusion is to find the bonding path with the least spatial repulsion, which perfectly explains common structures such as tetrahedrons and angular shapes. It also explains the basic principles of the formation of C₂H radicals, C₃ molecules, and isomers of C₂H₂ without introducing new theories. 10 ConclusionThus far, all four fundamental forces have been framed within the context of universal gravitation in this paper, though details may require further refinement. Limited by the resources available to the author, the entire text remains at a theoretical stage. Advancing this research would necessitate precise and systematic experimental protocols. Nevertheless, the theory proposed herein constructs a model of cosmic structure formation based on the interaction of particle clusters, simplifying the origin of the universe to the interplay between particles and universal gravitation. Compared to traditional cosmological models, this offers a more parsimonious framework. With its unique perspective, innovative theoretical structure, and potential scientific value, it introduces new lines of thinking to fields such as cosmology, particle physics, and optics, while also opening new avenues for future scientific research and technological progress. Although the theory requires further theoretical development and experimental verification, it undoubtedly provides a valuable contribution to understanding the deeper mechanisms of the universe. Sorry, I don't know how to delete or modify the previously - posted content, so I can only repost it for a better understanding.

-

Particle gravity cosmological evolution hypothesis

Abstract This paper proposes a particle-cluster dynamics cosmological model based on universal gravitation ("Dust Theory"), reconstructing the material evolution framework from randomly distributed irregular fundamental particles through gravitational interactions. The model reveals that particles self-organize into a three-tiered structure: the core (a low-kinetic-energy stationary center), the free layer (a dynamic particle zone dominated by potential energy), and the escaping particles (high-energy escaping particles). Particle clusters evolve hierarchically through collisions: initially unsaturated structures absorb escaping particles from the environment to expand their free layers; multiple particle clusters converge to form a "thermal environment" (where temperature is defined as a function of the kinetic energy and density of escaping particles); and when the free layer reaches saturation, the structure evolves into an "atomic" configuration—its core periodically radiates escaping particles, while its outer adsorption layer continuously exchanges with environmental escaping particles.Building on this, the theory provides a unified explanation for key physical phenomena:1.The nature of light: When atoms collide, interactions between their free layers generate impact particles, which are directionally transmitted via core energy to form a beam-like stream of escaping particles ("a photon"). This framework reconstructs double-slit interference: particle streams, after passing through slits, exhibit density-distribution superposition to form interference fringes.2.Thermodynamic mechanism: Heat is defined as the dynamic equilibrium between an atom’s adsorption layer and environmental escaping particles. Frictional heat arises from the stripping of free-layer particles, creating unsaturated zones.3.Electromagnetic origin: Static electricity results from disruptions in the free-layer particle cycle (e.g., wool friction temporarily stores particles before they are absorbed by adjacent atoms). Magnetic force is attributed to stable free layers constructing directional energy channels, enabling low-loss particle flow conduction.4.Fundamental forces: The strong interaction corresponds to the high-density resistance of saturated free layers (with an interaction range ≈ atomic radius), while the weak interaction stems from directional restoring forces caused by imbalances in adsorption-layer particle loss when atoms approach.This model connects microscopic particle behavior with macroscopic phenomena using universal gravitation as the sole foundation, challenging traditional multi-force frameworks (e.g., explaining acetylene linearity requires introducing the ad hoc "conjugate shortening" exception). It offers a parsimonious explanation for cosmic structure formation, force unification, and thermodynamic-light-electric-magnetic phenomena, though further experimental validation is required.

-

Particle gravity cosmological evolution hypothesis