Everything posted by Killtech

-

Relativity in Geometry and Physics

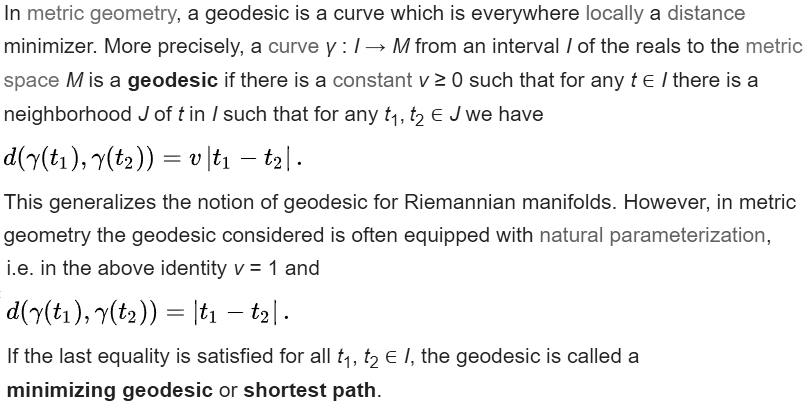

the general definition only requires to minimize distance locally, the extension of that condition to hold on the entire interval makes it hold globally.

-

Relativity in Geometry and Physics

I very roughly summarized the definition. technically, it is merely minimizing the distance locally. Like we know it from optimization problems, finding a local minimum doesn't guarantee at all it's also a global one. This can happen when there is more then one geodesic connecting two points with each other. The definition requires the existence of a continuous curve between the start and the end, so it only concerns a connected subsets of the space. You can find the definition here: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2007.09846.pdf and this is how this general concept translates into the special case of Riemann geometry: https://www.cis.upenn.edu/~cis6100/cis61008geodesics.pdf

-

Relativity in Geometry and Physics

I have to admit that i am a bit rusty in the field and had to look up a few things again. I mean no disrespect either but what you said is at least partially at odds with literature on geometry - because you leave important things out. While the connection is a fundamental tool in geometry, it is not actually used in most geometric definitions because it is only available under special circumstances. And whenever you talk about a LC connection, you forget that is is explicitly defined as a metric connection, that is via its compatibility with the metric (please check that if you don't believe me). So maybe let's start with clarifying a few things then. The concept of a geodesic as a generalization of a straight line in a curved space, is roughly defined as the shortest local path between two points (skipping some details). That is amongst the most general definition for which only a metric space is needed but no differentiable structure (hence no connection). Note that also the setup of Riemann geometry, the Riemann manifold, is defined minimalistically in terms of only a smooth manifold and a metric with no mention of a connection because being a metric space, the entire geometry along with the geodesic structure is fully specified this way already. However, for any practical use it is incredibly cumbersome to construct geodesics from that alone and since we are in a special case, we can make use of the additional tools available. This is where the LC connection comes into play. Aside from being torsion-free, its other defining property is that it must be compatible with the metric on the Riemann manifold. Only the combination of both conditions makes the connection unique. The second condition is crucial because it assures that the geodesics constructed via the connection agree with their metric definition - and frankly speaking this is the core motivation for that definition. The torsion-free is chosen for simplicity and more importantly to make it unique. In case of Riemann geometry, the definition of geodesics via parallel transport is equivalent to their metric definition through that link. But that of course requires that we cannot treat the connection as independent from the metric at all. What you write sounds as like lengths, angles and volumes are effectively independent of the geometry. but you are aware that angles are a way to express whether two vectors are orthogonal or parallel or in between? So your independent metric may get into an argument with your connection about its idea of a parallel transport. Yes, this is very helpful! Albeit i will have to do some reading before i can sort out how these relate to what i want to look into. Give me a few days. I'm sure i'll back full of questions

-

Relativity in Geometry and Physics

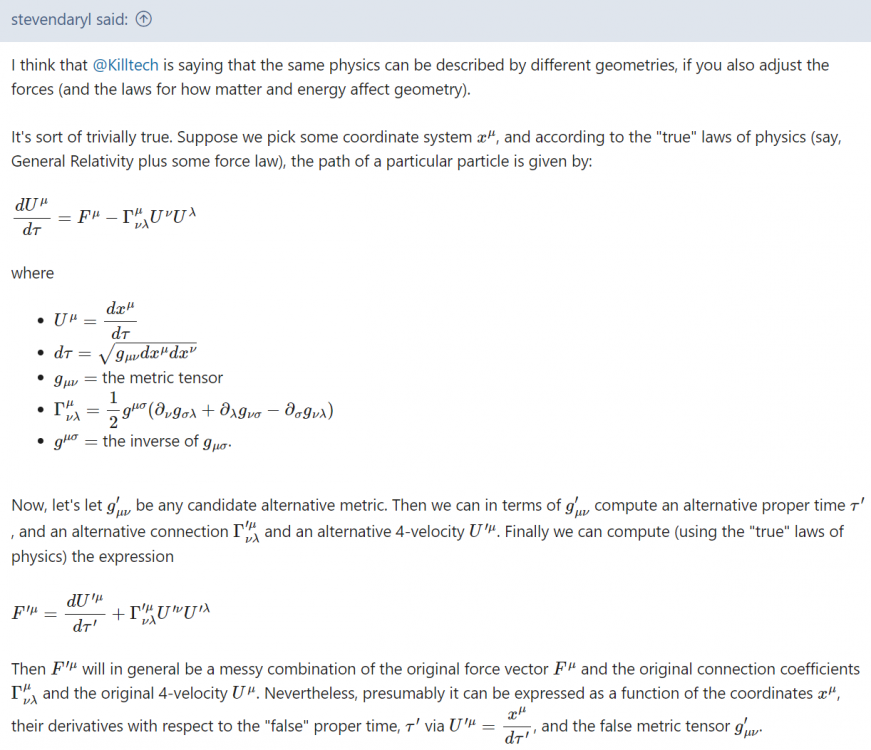

Steven's post was the best and shortest summary of what i intend to discuss - and yes, just as Poincaré implies and Steven writes, the change of geometry entails the change of laws physics. Einsteins field equations are linked with a very specific interpretation and geometry. Changing the latter requires to update the prior. The starting point is that i want to use different devices as clocks which will produce time measurements that will disagree with the proper time general relativity expects. Instead of discarding these devices as false, i intend to find a model that fits them and therefore I need a metric tensor that is able to reproduce their time measurements. Measurements with such clocks naturally will also show a disagreement when testing various laws of physics as we know them, hence we do indeed need different laws to make the new clocks work. Your link is a bit general. can you tell me which chapter i should be looking up in more detail? when comparing Newton's old theory to the relativistic case, we find that it is itself a collection of different proxy models, because we have to choose the frame in which gravity acts instantaneous. depending on the choice/definition what we consider simultaneous in reality, we get each a model that will produce slightly different predictions. Furthermore, we need to interpret Newton's model and in particular each time measurement. Do we use an interpretation where any SI-clock is a valid measure of the absolute time or do we identify Newton's time with a coordinate time like TDB? while that does not change the working of the physical model itself, this has big impact on translating measurements into initial conditions and later back into predictions we can compare with experiments. Newton's gravity is by no means a uniquely determined theory either. Hmm, not sure what you have trouble with here. As you can see from Steve's post we have two connections Gamma and Gamma' wich are both derived via the formula from their corresponding metric tensor g or g'. That formula is what makes each into an LC connection of the corresponding geometry. Since both manifolds use the very same set and coordinate map, we can evaluate all those terms in those coordinates at each location and find they are simply different matrices. Let's go back to the simple case of a single differentiable manifold, which in one case we equip with a Riemann metric to make it into a sphere and in the other we pick a another metric to make it into an ellipsoid. Both cases have each a metric tensor and an associated LC connection. But the LC connection on a sphere cannot be the same as on an elipsoid. A LC connection is only unique per each Riemann metric - therefore on a single differentiable manifold we have as many LC connections as we have valid tensor fields that fulfil the requirements of a Riemann metric (bilinear, symmetric, non-degenerate everywhere). I would be very interested in looking these up. It's quite possible i was looking (googling) for the wrong thing and my results just came up empty.

-

Relativity in Geometry and Physics

Yes, a covariant form is as you say independent of the choice of coordinates - but i do not intend to change the coordinates. The issue is that "changing the metric" has an ambiguous meaning, because in physics it's used differently - because the actual metric is never considered to be changable. Physics don't consider the possibility that the very same physical situation can be described using different geometries. Analog to how we can freely choose coordinates, mathematics does actually allow to change the geometry as well, for as long as the topology is shared. Consider that Newton's classical theory of gravity and Newton-Cartan theory represent the same physics, yet they achieve the same predictions by the use of different geometries. I do assume to always use a Levi-Civita connection as you can see from the formulas in my last post. I left out the connection mostly because i prefer to have it compatible with the metric and therefore implied by the known formula for the Christoffel symbols. But in my case it is applied to a different tensor, hence the resulting connection is different as well. I haven't said that explicitly but it's in the formulas i have posted. If we agree to restrict to LC-connections, it is enough to specify only the metric tensor. If the formulas in my example weren't enough or the idea too unfamiliar, note that a Weyl transform is a special case of this, however it has a different purpose and i don't intend to restrict to rescaling of the metric but rather any local transformation that preserves the rank of the tensor. The idea is indeed to redefine the meaning of lengths, angles and what is parallel: what one metric tensor (and its connection) may consider orthogonal, another may not! In mathematics we know that we can work with different definitions of orthogonality all the same - it is just not trivial to find the proper interpretation of what that means. Same as using different coordinates requires using a different interpretation for each point is (i.e. (0,0,1) is a very different location in polar then in cartesian coordinates), we must adapt our interpretation when using a different geometry similarly (lengths, angles etc.). You are right, that if we change the connection and leave the interpretation unchanged, we will get a different model that will make wrong predictions. However if we change both the model and its interpretation accordingly, we can leave all predictions untouched.

-

Relativity in Geometry and Physics

Okay, from your responses i see we are talking past each other. All you say is true, but it is also not exactly related to what i was writing. Let's go back to the example of a single differentiable manifold that we can make to be either an ellipsoid or a sphere depending to what metric and connection we define on it. Because both are build on the very same manifold however means that any covariant tensor equation in the ellipsoid geometry can be translated into one in the sphere geometry like this: (btw. how do you use latex here around these forums when in need of writing down some formulas?) There is also an interesting discussion of this by Henry Poincaré you can find here in section XII: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Foundations_of_Science/The_Value_of_Science/Chapter_2 It discusses the difficult relation we have in physics where in order to conduct any measurement at all we need to start with some assumptions. These kind of assumptions must be distinguierend from other physical laws as these assumptions are not testable in an experiment as Poincare remarks. For example: you will find that we cannot simply assume the speed of light to be non-constant as this - given how we define the measurement of time and distance - will produce contradictions whenever we try to model these measurements with such an assumption. Anyhow, once you have made a transition to another geometry, you have to be very careful with the interpretation. if you use the wrong one, the new model will of course make wrong predictions. But same as for general relativity, you first have to deduct the correct clocks and rods that are represented by the new metric tensor and its connection. And only then the combined model and interpretation will yield identical prediction to your starting theory.

-

Relativity in Geometry and Physics

Thanks. I understand that construction. Note that it is called the "geodesic clock" and as the name suggests it is constructed via geodesics. A geodesic is defined via the geometry and more precisely the Christoffel symbols derived from the metric tensor of said geometry. As i tried to highlight, the definition metric tensor already implies a what clocks and length measurements must produce. The theory of relativity never formally defines what we should count as a clock even though Einstein uses the term a lot. But we can't just use any oscillators because each may be impacted differently by the environment at a given location and frame (unless we properly correct for the deviances). The geodesic clock is actually a theoretic derivation what clocks we must use to be to consistent with Einsteins theory and atomic clocks are constructed/defined and corrected in just such a way to be as close as possible to that ideal. This is why what you posted is so very significant - it gives us the final details for a most accurate interpretation of the theory. I am however looking at using a time standard instead of proper time which is a major difference. I should maybe again highlight that TDB is normally not thought in terms of clocks for the good reason to avoid confusion. In fact TDB time has to be calculated via an atomic clock (which is the most accurate implementation of an ideal clock of general relativity) and correcting it by the influence of gravity (which requires additional information) so it is not just more complex method, but also explicitly deviates from what a theoretical clock should yield. Note that most clocks we use in daily life are invalid in the context of relativity because they don't measure proper time but also give time according to a time standard. So if you were to climb Mount Everest with two clocks, one radio-synched watch and an atomic clock we will find a discrepancy: the UTC time standard simply ignores our actual location whereas an atomic clock doesn't, hence general relativity will make them run apart over time - yet neither is going off. They just measure different things! It is important to understand that. What i am looking for is the question if physics skipped the part where the mathematical discipline of Riemann geometry is so flexible that it allows us to treat TDB as if it was a time measure we could base clocks on for physical experiments. Of course it has practically a limited use since measuring time in SI-seconds allows for a much greater accuracy the measurement in TDB which inherit a big uncertainty from the gravitational correction which is hard to measure and calculate precisely. Then again, if we want to calculate whether two celestial bodies will eventually collide, we have that error one way or another.

-

Relativity in Geometry and Physics

This is the bit what i am currently struggling with in physics. Relativity is a concept deeply rooted in the nature of geometry itself because we must always account that space and time are never measured absolutely but in units - and those are always relative to some local and frame dependent reference. For the SI second this is a specific Caesium transition frequency at the observers frame and location. When something is said to be constant it merely means it changes exactly the same as the reference in units of which it is measured. Because all measurement is relative, it is impossible/meaningless to determine if something changes in an absolute sense, hence it is crucial to understand the entire geometric formulation is about relative metrics and distances. But from what i learn from physics, i did get the impression it lacks understanding of the full extend of relativity and its seems stuck in interpreting everything within a singular view. So the baryocentric metric representation discussed here is just one example to show how relative the entire geometry is beyond what is usually used in physics. To go into detail, let's start with a motivation. In the beginning of the 19th century, time didn't not have the same importance it has in our todays society. Back then each town might have had its own non uniform local time and clocks. Only when rail tracks between the cities were build, time became of higher importance as we needed to organize events in between different locations. The railway time was introduced as an unifying standard and one of the early time standards which effectively became GMT/UTC our clocks still reference today. In general relativity we have a little bit of a similar scenario with each frame having its very own proper time and clock. The reasons may differ, but the practical problem this creates are the same, hence IAU introduced the TDB coordinate time [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barycentric_Dynamical_Time] that serves the purpose of 'railway time' for the solar system. Let's assume i would be an interplanetary traveler and have to buy a clock, then what concept of time would i want it to show? or let's say i want to record the historic accounts of a interstellar civilization - what time should i use? Proper and coordinate times are very different representations of time for different purposes, both perfectly valid in their own right. But for our intuition, the one is a lot more abstract then the other, so i was wondering what happens when we formulate general relativity in a different time? Measuring time differently, or rather measuring a different time has a lot of implications. TDB corrects for the effects of gravity fields to proper time - so at the edge of the solar system SI and TDB clocks may yield same numerical results, but on earth TDB clocks will run relatively faster. Consequently, if we were to use such clocks to measure the speed of light in vacuum, we find that light signals appear to travel slower in earths gravity well then at the edge of the solar system. There is no contradiction here because TDB clocks results have to use an own coordinate time unit (i.e. not the SI second), and these units are locally different from SI, allowing no simple comparison. Mathematically however, we do have the means to adequately predict how physics will look when we keep using such units. Now this is where the discipline of geometry comes into play. First, let's recount what is mathematically the difference between a sphere and an ellipsoid Riemann manifolds? Technically we can take the very same subset of R^3 for both manifolds and use the very same coordinates for either. The actual difference is in fact how we define to *measure* length along a line element. Or more generally, the metric tensor we define on the manifold. Even though geometry is a mathematical discipline the practical concept of measurement is a fundamental part of the theory (as the term "metric" implies) - which the metric tensor represents in a abstract way. Now going in back to TDB clock question, we need a metric tensor that is correctly able to represent TDB time along a line element. We can do that do that with length as well i.e. using BCRS coordinate lengths [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barycentric_and_geocentric_celestial_reference_systems] to yield a new metric tensor representing measurements done with the corresponding coordinate units. Admittedly it does not make practical sense with just any coordinates, but for these, the results can be well interpreted. For example the coordinate distance between earth and moon is almost constant since it does not depend on the overserves frame i.e. it is always a specific proper distance. Geometrically speaking, we exchanged the metric tensor g of general relativity for another - and i don't mean its coordinate representation - I really mean to have exchanged the whole geometry. Because we exactly know how these two metric tensors relate to each other at every location, we can write down a transformation procedure to reformulate Einsteins field equations with their original metric tensor to the geometry implied by the TDB-BCRS metric tensor. Of course that does not change physics in any way - we just change the point of view (i.e. measurement) to yield a different model of physics but with a new interpretation (mapping time and space to different clocks and measurements). If we consistently exchange a physical model along with its interpretation for another, the changes in both cancel each other out in a sense: mathematically speaking we have a commuting diagram [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commutative_diagram] where the interpretations takes the role of the morphisms while the models and reality are the nodes/vertices. If we were to look at Maxwells equations in barycentric coordinate units specifically, the transformation prescribed from Einsteins metric tensor to the barycentric geometry will introduce a gravity induced refractive index to the vacuum, stemming from the gravity correction to TDB clocks. As such in the new model (and its units) the speed of light is not a constant and the bending of light by gravity is now described via refractive index instead of the geometry. The actuary predictions however remain ultimately identical. I should also mention that the barycentric nature of these coordinates means the new model has chooses a preferred frame. and since it measures time intervals and length in coordinates differences i.e. entirely invariant of the observers frame, Lorentz transformation will now distort those. Instead it is more natural to go back to Galilean transformations which preserve these. But looking at Maxwell in vacuum, this now means that this equations looks like a classical wave equation in a medium. Furthermore gravity itself will also appear back as a force field (and some other additional fields). An increase in complexity which is compensated by trivializing the geometry. Conceptually this is similar to a reversed Newton-Cartan approach, where we take general relativity and translate it back to a Newtonian-like "absolute time" (which TDB is).