-

The Fundamental Interrelationships Model Part 2

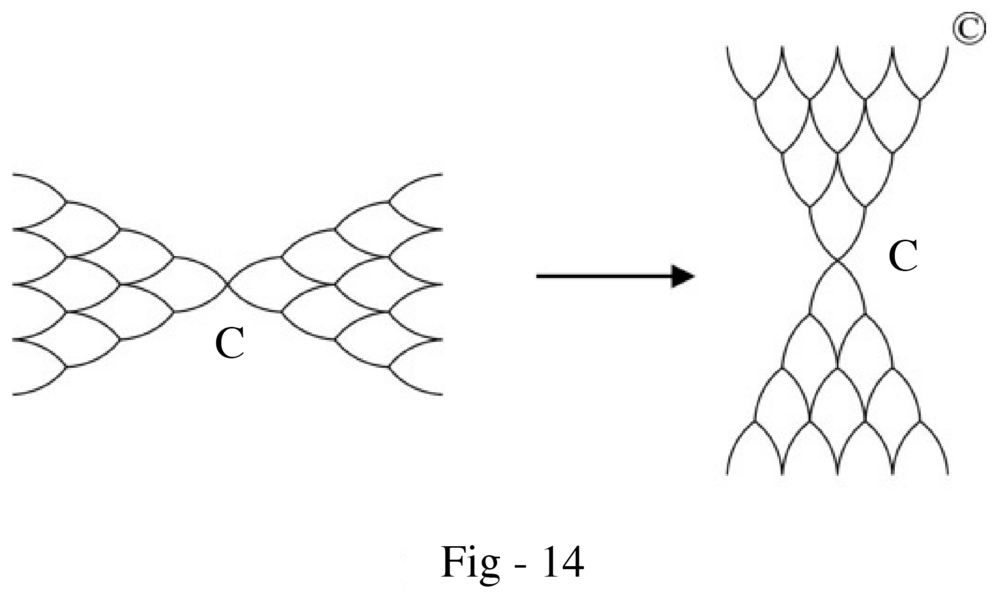

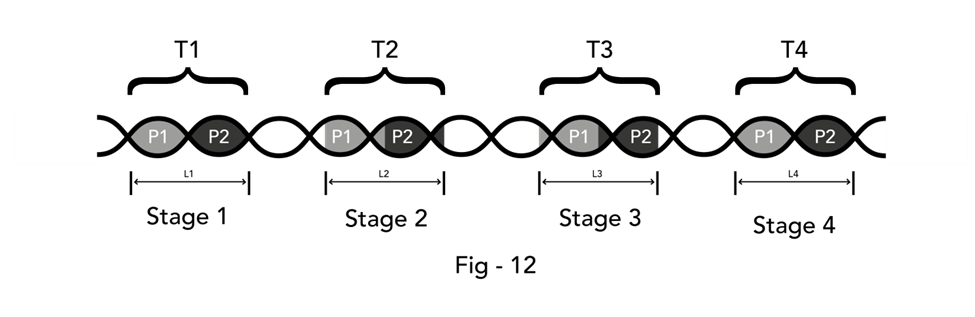

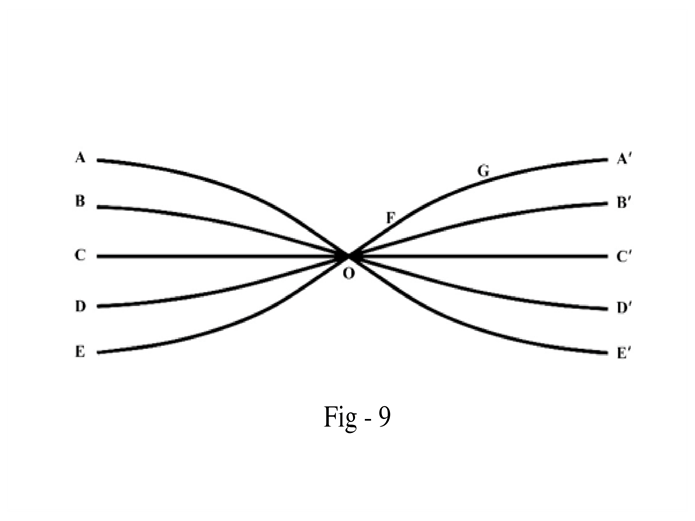

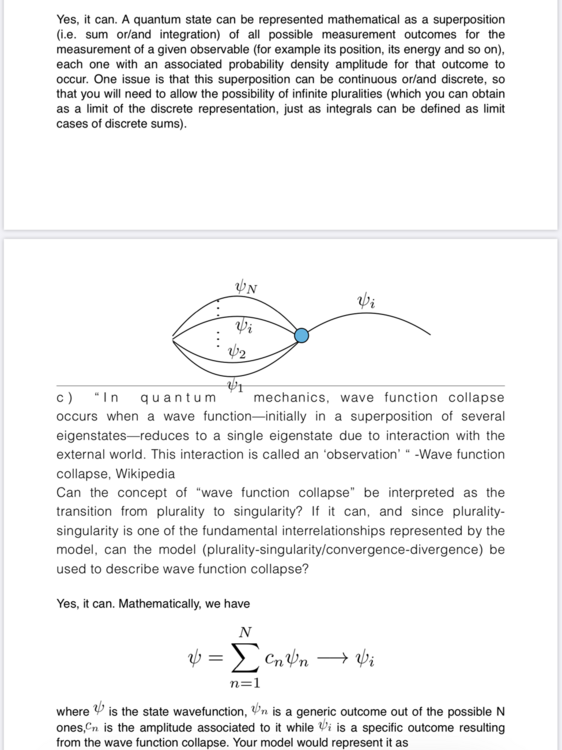

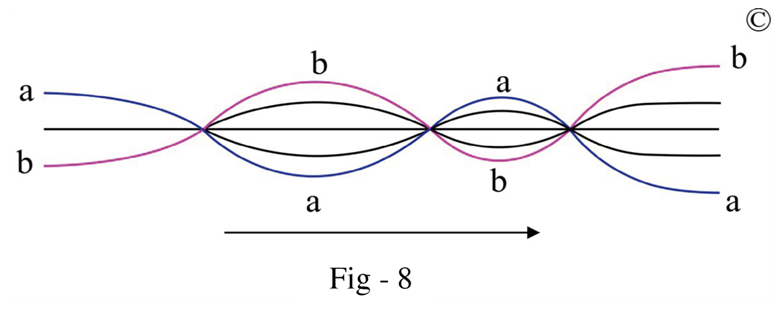

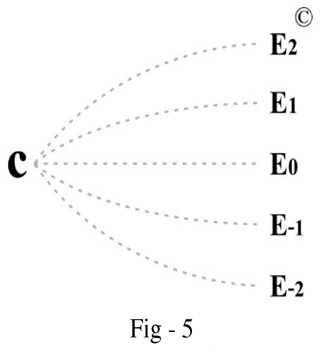

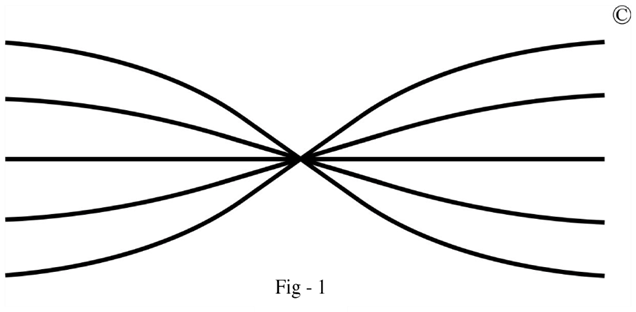

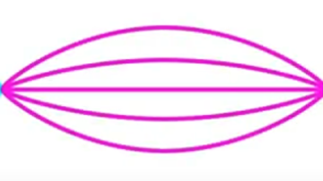

Can we foresee the fate of civilization through the lens of melting ice? Yes, we can. This perspective serves not as the crystal ball of a fortune-teller, but as a reflection of the fundamental interrelationships that govern the universe. Let’s take a look at an ice cube melting. When the temperature is below 0 °C, the water molecules in ice are arranged in an orderly manner, forming a stable crystal order.[95] As the temperature rises, the kinetic energy of the water molecules increases, expressed through greater molecular vibration. When the temperature reaches the transition point of 0 °C, the molecules’ kinetic energy surpasses the binding force that maintains their orderly arrangement. Once this binding force can no longer hold the molecules in place, the stable crystal order disintegrates (divergence).[96] The ice cube then transforms from a stable solid form into an unstable liquid form — a process known as phase transition. After the crystal order breaks down, the water molecules are no longer confined to fixed positions within the ice cube. They begin to move freely and disseminate in all directions as the ice melts. In solid ice, the movement of water molecules is restricted by the crystal’s binding force,[97] but in liquid water, this restriction disappears and molecular motion increases dramatically.[98] This illustrates that the degree of freedom of water molecules increases with their energy. As temperature continues to rise, liquid water transforms into gaseous steam, accompanied by a dramatic increase in volume. This represents expansion driven by increased energy. Meanwhile, the orderly arrangement of water molecules in the ice crystal transforms into disordered form in the liquid state, and the molecules collide with one another, generating intensified interactions. Technological development’s impact on society follows the same set of fundamental interrelationships that govern the Big Bang, the evolution of life, and the development of multicellular organisms. Thus, it mirrors the same underlying order shared by those processes. Transition point When a major technological breakthrough occurs, human capability reaches a change point – a critical moment that marks the beginning of a new stage in social evolution. In ancient times, the invention of stone, bronze, and iron tools each marked the onset of their respective ages. In modern history, the invention of the steam engine heralded the Industrial Age; the creation of the first computer initiated the Information Age; and the emergence of genetic engineering signaled the dawn of the Biological Age. These technological change points, which trigger fundamental transformations in society, represent pivotal moments that lead to profound social evolution. This process parallels the change points in the evolution of the universe described by the Big Bang theory, as well as those in the evolution of life itself. Transition of state When technological transition points are reached, societies enter a “phase transition”. This process is analogous to solid ice melting into liquid water — a transformation in which the substance’s physical properties change fundamentally. Likewise, different phases of society possess distinct social properties. In the present day, humanity is undergoing the “phase transition” brought about by the Information and Biological Revolutions. These two revolutions generate immense power, driving profound transformations in the social properties of human civilization. In these social transitions, the old social order ceases, but civilization continues — a reflection of the fundamental interrelationship of continuation – discontinuation. Expansion With the utilization of tools, human power expands. Each technological advancement enhances individual capability — progressing from stone, bronze, and iron tools to steam engines and computers. These developments reveal how personal and collective power increase in step with the evolution of civilization. Power increase leads to expansion, whether within individuals or groups. This process parallels the volumetric expansion of steam when water reaches 100 °C – a physical expression of accumulated energy transforming into increased volume. As power grows, certain social activities expand correspondingly. During the Industrial Revolution, for instance, the introduction of machinery amplified the productive power of farm owners, enabling the expansion of both farmland and output. Likewise, industrial production itself expanded under the momentum of mechanization. As individuals’ power expands in the Information Revolution, many are extending their businesses into territories that were previously accessible only to large companies. This reflects the fundamental interrelationship of expansion, which paves the way for new opportunities. Contraction Alongside expansion, contraction inevitably occurs. Many individuals lose influence, leading to the contraction of their businesses. This process is governed by the fundamental interrelationship of contraction and often manifests as devaluation. As previously discussed, exchange generates commercial value. In the absence of higher-level regulation, market prices are largely governed by the law of supply and demand: prices rise when demand exceeds supply, and fall when supply surpasses demand. An increase in individual power can be expressed as the enhanced ability to produce and provide goods to the market. When more individuals possess such capability, overall supply expands, leading to a decline in prices. Moreover, as individuals gain greater power, they become increasingly capable of fulfilling their own needs and desires directly, reducing external demand. Both factors contribute to price reduction — a process that results in commodity devaluation. When the decline in commercial value involves production equipment, it leads to capital devaluation. More broadly, devaluation may affect not only capital but also technology and labor. Ultimately, devaluation is an inevitable consequence of the continual increase of individual power within the evolution of civilization. Devaluation can be interpreted as an expression of the fundamental interrelationship of contraction Divergence Expansion driven by increased power can also manifest as divergence. For example, with the adoption of machinery, a farmer not only expands the scale of operations but also diversifies into new forms of production and enterprise. Convergence Convergence occurs when individuals, after acquiring expertise and resources, unite to form new organizations or enterprises. This phenomenon reflects the natural tendency of capable individuals to come together through shared purpose and complementary strengths. Increased Independence and Degree of Freedom When the temperature rises to 0 °C, the kinetic energy of water molecules exceeds the intermolecular binding force that holds them in place.[99] They break free from this restriction and are no longer locked into fixed positions. The space through which they can move increases dramatically, signifying a greater degree of freedom. Similarly, as an individual’s power increases, the range within which they can act also expands. For example, motor vehicles externally augment human muscular power, enabling individuals to travel across far larger areas. This represents an increase in personal freedom. Furthermore, as individual power grows, dependence on others decreases. Reduced reliance diminishes social constraints and thus enhances independence and freedom. In earlier times, human beings clustered together in villages, towns, cities, and metropolises. Why do people live in such concentrated ways? The reason lies in limited individual power. To satisfy their needs and desires, individuals must exchange goods and services — and distance hinders exchange. Proximity therefore facilitated cooperation and survival. However, the Industrial Revolution transformed this condition. By externally amplifying muscular power — especially through the invention and proliferation of motor vehicles — individuals gained the freedom to live farther from urban centers, where land was cheaper and environments were more pleasant. Despite increased distance, the power provided by the motor car sustained the ability to exchange and connect. This transformation exemplifies an increased degree of freedom — the liberation of individuals through the augmentation of power. Symmetry–Asymmetry However, the increase of individual power also follows one of the fundamental interrelationships – symmetry-asymmetry. The growth of power among individuals is never uniform: some experience greater increases, while others advance less. This uneven distribution represents asymmetry. In another form, one individual’s gain may correspond to another’s loss — an expression of symmetrical opposition often summarized as “one person’s gain is another’s loss.” Both patterns, whether unequal advancement or reciprocal reduction, are manifestations of the fundamental interrelationship of symmetry–asymmetry. As individual power rises, independence and the degree of freedom likewise expand. During the Industrial Revolution, for example, farm owners gained increased autonomy and mobility through the use of machinery — a pattern also observed across other industries. Yet, under the governance of symmetry–asymmetry, the independence and freedom of the labor force diminished correspondingly. Despite this dynamic of gain and loss within human society, the overall trajectory shows a gradual reduction of humanity’s dependence on the natural environment. The tendency to social disorder Stronger Interaction As the temperature of water rises, its molecules gain kinetic energy, resulting in more frequent and forceful collisions that create stronger interactions. Similarly, when individual power increases dramatically — particularly through the adoption of new technologies — interactions between individuals become more intense. For example, during the Industrial Revolution, the rapidly expanding power of individuals engaged in industrial production collided with the interests and activities of small workshop owners, laborers, and farm operators. These intensified interactions illustrate how technological empowerment amplifies social dynamics, generating both cooperation and conflict within society. The intensification of interactions within a system often gives rise to greater disorder and complexity. Social disorder As previously discussed, when power at a lower level of a hierarchical system increases, the asymmetry between higher and lower levels may shift, potentially destabilizing the system. This is especially true when the lower level’s power surpasses that of the higher level. If the higher level cannot proportionally increase its control, it becomes harder to regulate individual behavior, and society risks descending into disorder. This process is analogous to ice melting. As temperature rises, water molecules gain kinetic energy. Once their energy exceeds a critical threshold — the “higher-level” binding force — the orderly crystal structure disintegrates. Similarly, when lower-level power exceeds the controlling influence, social order can break down. As individual power grows, so does the range of influence — or power territory. Strong interactions between empowered individuals may lead to conflicts, particularly when the expansion of some encroaches on the space or interests of others. Without adequate mechanisms to manage these tensions, the system may slip into disorder. Furthermore, the increase of individual power can conflict with established rules that maintain social cohesion, such as laws, morals, ethics, religion, or even external regulatory forces. Commercial and economic changes can amplify this effect: for instance, when production equipment loses value due to market dynamics, it can trigger capital devaluation, affecting technology, labor, and broader social structures. Ultimately, the rise of individual power, while driving progress and freedom, simultaneously increases the potential for social disorder if not carefully balanced within the larger system. All these discussions clearly demonstrate that social systems and inanimate phenomena share a common underlying mechanism, reaffirming the fundamentality and universality of these interrelationships. I will reply to you in due course.

-

The Fundamental Interrelationships Model Part 2

In the video, the Cartesian coordinate system addresses this issue. Please excuse me, I’m not sure I follow. Could you clarify what you mean by “no forces” in this context? There is no “rocket equation” in the IRM, but it can approximately represent the course of a rocket. Thanks for your input. I’ve looked it up online.

-

The Fundamental Interrelationships Model Part 2

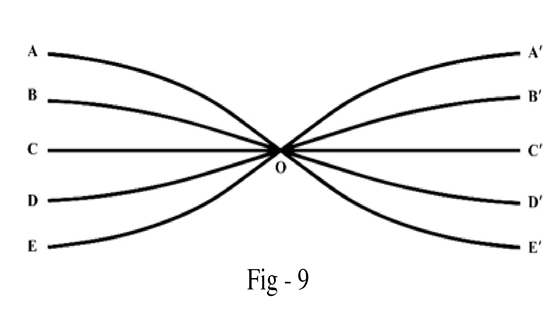

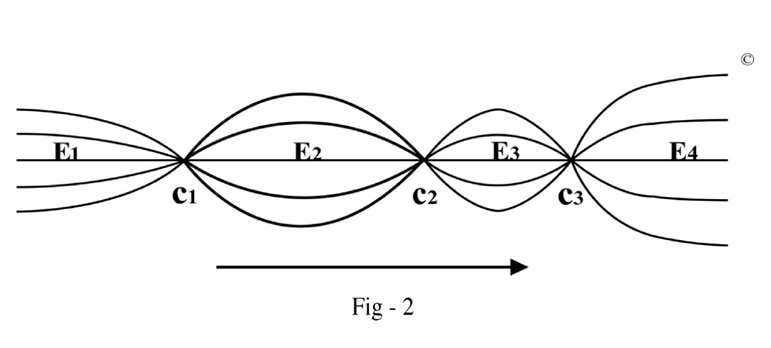

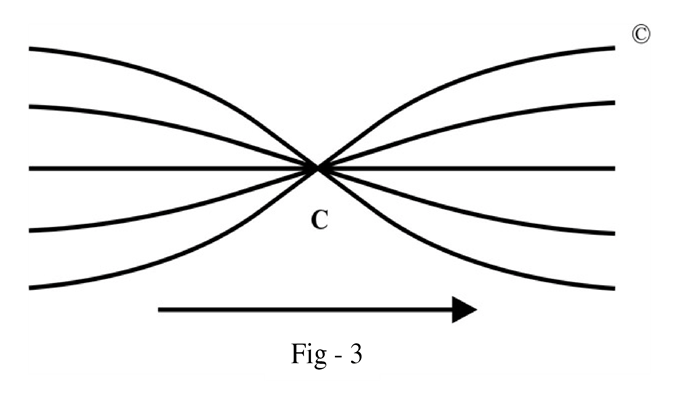

I appreciate your perspective, but Newton overlooked one of the fundamental interrelationships — limitation. That’s precisely one of the main points of debate surrounding Newton’s laws. Can you give an example of anything that could have limitless speed? In reality, unlimited speed does not exist. Hence, Newton’s laws are valid only within a limited and conditioned framework, as represented in the IRKM. In the video, on the left section of the IRM, two symmetrical curved lines on opposite sides of a horizontal line, proceeding from left to right, converge at a single point on that line. This represents two opposite forces acting on the same object. If you accept this illustration, then in the right section of the IRM, two curved lines diverging from each other represent two opposite forces not acting on the same object. This dynamic illustration clearly shows that “the two forces mentioned in N3 act on different bodies,” and the statement that “your diagram suggests they act on the same body” misses the point. Regarding the Second Law, my video from 0:50 to 1:19 explains it completely. “What holds B in place in those circumstances?” This depends on the context. It is different in water, in space, and on a hard surface.

-

The Fundamental Interrelationships Model Part 2

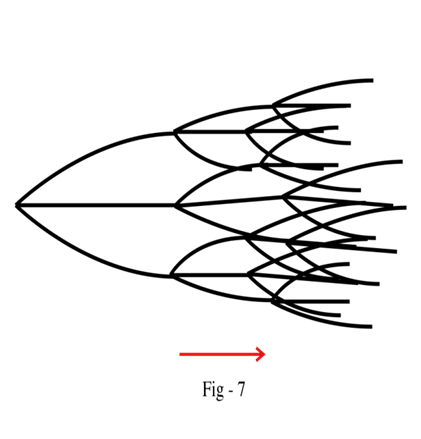

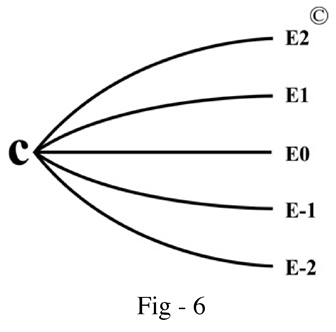

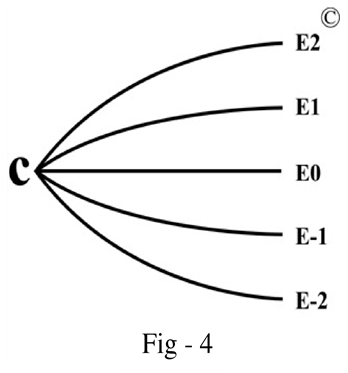

You have made many valid points. If my understanding is correct, the key idea can be summarized as follows: Our human capacity to understand the universe is limited, whereas the universe itself is unlimited. Therefore, it is impossible for human beings to fully comprehend an unlimited universe. Consequently, no theory can ever encompass the entirety of the universe — meaning that a true Theory of Everything (ToE) is impossible. Indeed, limitation is one of the fundamental interrelationships within the universe, manifested in the fact that every system is limited. This concept is highly reliable because it is supported by countless observations. Conversely, the interrelationship of limitlessness is also fundamental, referring to the scale of the universe. This concept arises from the tendency that beyond any system, there may always exist another system — and this progression continues indefinitely. Thus, how could human intelligence, being inherently limited, ever encompass an unlimited universe? The answer is: impossible. Moreover, since we still cannot clearly define what the universe actually is, how can we define what everything is? At present, the concept of the universe usually refers only to the “observable” or “known” universe. However, these definitions imply that our concept of the universe encompasses only a portion of the true universe. Similarly, the “everything” we refer to is actually only a part of the true everything — that which is known to us. Yet even within this limited “everything,” we still lack a unified theory. The search for such a theory — one that can explain all aspects of our known universe — is what we call the Theory of Everything. Although the human mind is limited, we can still attempt to create conceptual models that represent the part of “everything” we do know, while symbolizing the parts that remain unknown. The IRM provides such an alternative framework, as it embodies both limitation and limitlessness. Limitation is represented by the IRM’s ability to reflect the boundaries of human cognitive capacity, while limitlessness is represented by its endlessly extending and branching lines. Therefore, the concept of limitation–limitlessness expressed through the IRM can effectively address the issues you have raised. Thank you for your insightful and thought-provoking questions and comments. I will prepare and provide comprehensive responses in due course.

-

The Fundamental Interrelationships Model Part 2

Thanks for correcting me; I truly appreciate your input. Thank you for your insightful input, which I have received and appreciated. I have also noticed and read your previous related idea and will respond with more details in due course.

-

The Fundamental Interrelationships Model Part 2