-

Can Frequency Determine How Matter Couples to Gravity or EM Fields?

Here we go: Equation 1: |Ψ_gravity⟩ = Σ α_{n₁,n₂,...,nₖ} |n₁P₁, n₂P₂, ..., nₖPₖ⟩ ⊗ |G_effect⟩ n₁, n₂, ...: Number of particles of each type P₁, P₂, ...: Particle types (like protons, electrons, etc.) α: Weighting factor for each configuration ⊗ |G_effect⟩: Resulting gravitational influence for that setup This builds a sum over different combinations of particles and their estimated gravity impact. Equation 2: ΔG(r,t) = Σᵢ [Nᵢ × Cᵢ × S(rᵢ,t) × D(|r - rᵢ|)] + I(r,t) Nᵢ: Number of particles in group i Cᵢ: Coupling strength S(rᵢ,t): Localised activity (position + time) D(|r - rᵢ|): Distance-based decay I(r,t): External influence or background field I'm just building a simplified framework to test particle setups and see how they might collectively produce localized gravitational effects.

-

Can Frequency Determine How Matter Couples to Gravity or EM Fields?

I’ve been exploring conceptual approaches to gravity manipulation. I started by thinking of gravity less like a geometric curvature and more like a dynamic medium, similar to how air or water can be disturbed. The idea is that if particles create ripples in this medium, perhaps we can coordinate their properties and trajectories to locally influence gravitational effects. To explore this, I’ve formulated two equations and built a working computational framework to test particle interactions numerically: |Ψ_gravity⟩ = Σ α_{n₁,n₂,...,nₖ} |n₁P₁, n₂P₂, ..., nₖPₖ⟩ ⊗ |G_effect⟩ ΔG(r,t) = Σᵢ [Nᵢ × Cᵢ × S(rᵢ,t) × D(|r - rᵢ|)] + I(r,t) The first equation represents a quantum superposition of particle combinations and their associated gravitational influence. The second describes how particle properties and spacetime positions might sum to produce a measurable gravitational deviation at (r,t).

-

Can Frequency Determine How Matter Couples to Gravity or EM Fields?

Thanks, not sure why I got lost down that thought, anyway just another 9,999 more things to get wrong before I figure out something important! Cheers for setting me straight guys.

-

Can Frequency Determine How Matter Couples to Gravity or EM Fields?

Thanks for the reply and fair point on both accounts. I'm not trying to suggest that gravity doesn't couple to high-frequency particles like photons (gravitational lensing confirms that clearly), but more wondering whether the strength or characteristics of that coupling, might vary depending on the energy state or vibrational frequency of a system. So rather than saying “gravity doesn’t couple to fast-moving particles,” I'm trying to ask whether that coupling might behave differently, or at least perhaps be, less functionally relevant, in engineered systems where high-frequency EM fields dominate, especially compared to stationary or low-frequency rest mass systems. Appreciate the clarification though that helps narrow the question.

-

Chris1000K changed their profile photo

-

brain just wants to be happy, what to do in life, try to be happy? Boring isn't it?

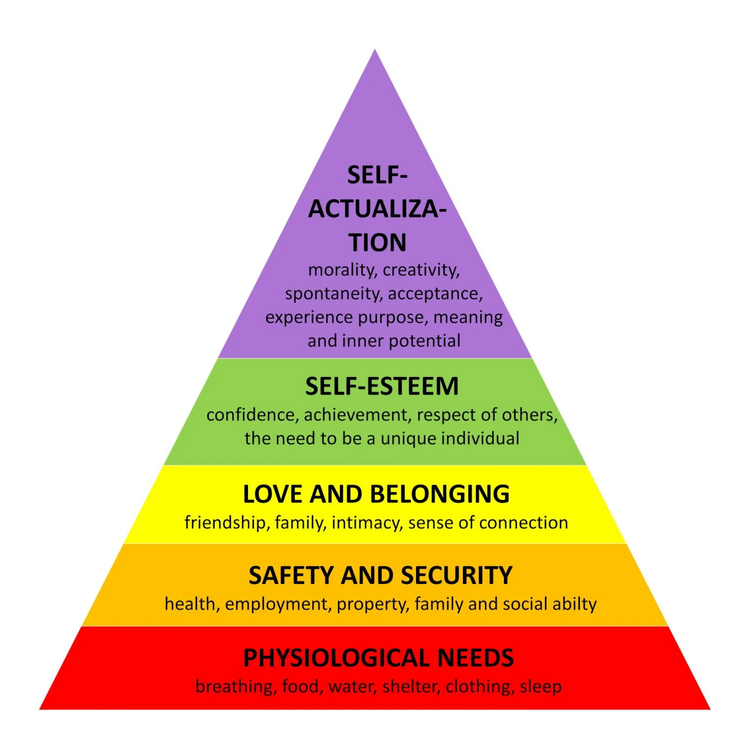

One way to look at this is through Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (see image). It’s a psychological model that helps explain what our brains might actually be aiming for when we talk about happiness. Maslow suggested that human motivation happens in stages. At the foundation, we’re driven by basic survival needs like food, water, and rest. Once those are taken care of, our focus shifts to safety, then social connection, then achievement, and finally to things like purpose, creativity, and fulfilment. The idea is, that we don’t seek “happiness” directly. Instead, we pursue things that meet our needs at different levels. When we satisfy those needs, our brains give us a kind of chemical reward, like a hit of dopamine or serotonin. That’s what we experience as happiness. So happiness isn’t really the goal. It’s more of a signal that we’re on track. For one person it might mean comfort, for another it might mean achieving something difficult, or having deep relationships, or solving problems. The question about whether this serves some greater cause or system we’re unaware of, is a fascinating thought. From an evolutionary point of view, our behaviours often support survival and reproduction, whether we’re conscious of it or not. But it’s definitely worth thinking about whether happiness itself could play a role in something bigger than individual experience.

-

Can Frequency Determine How Matter Couples to Gravity or EM Fields?

Hi all, This is a speculative question, but one I’d really appreciate input on from those with a stronger grounding in field theory and quantum mechanics. We know that gravity and electromagnetism are fundamentally distinct forces, but they share a number of interesting parallels: both act at a distance, follow the inverse square law, and interact through continuous fields that permeate space. That got me wondering: Could it be possible that gravity and electromagnetism interact with matter based, at least in part, on the frequency of the particles or systems involved? In other words: Electromagnetism seems to couple most strongly to high-frequency, fast-moving particles like electrons and photons. Gravity, in contrast, may couple more directly to slow-moving, low-frequency systems atoms, massive particles, and macroscopic bodies. If this were true, gravity and EM might represent different parts of a broader interaction spectrum not unified in the traditional sense, but differentiated by the types of vibrational states or frequency bands of matter they interact with. Some implications or questions that come to mind: Could this perspective help explain why we can manipulate EM fields so easily, but not gravity? Might strong EM fields partially shield or modulate gravitational effects, simply by engaging different energy states? Could this point toward any possible experimental approach even if just conceptually for frequency-selective gravitational interaction? Are there theories or prior experiments that might touch on this idea from another angle? I’m aware this idea is speculative and may well conflict with established theory but I’d love to know if there’s a framework (either classical, relativistic, or quantum) where this line of inquiry has been explored, even partially. Thanks for any insight.